The right place to start: cosmopolitan Riviera, France

Author

- Alessandro Silva

Date

- December 16, 2003; a pre-publication of the book BACK ON TRACK, Sept 9th, 1945 to May 13th, 1950 (Chapter I) by the author

Related articles

- 1946 GP des Nations - How the great Tazio came to ignore a black flag... and get away with it, by Leif Snellman/Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/'Uechtel'

- 1947 Italian Championship - The race when Nuvolari waved the steering wheel at the crowd and a forgotten Championship, by Alessandro Silva

- Alberto Ascari - Cursed natural talent, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/Leif Snellman

- Delage - A World Champion manufacturer, by Leif Snellman/Josh Lintz

- Delahaye - René Dreyfus and the upset at Pau, by Leif Snellman

- Philippe Étancelin - Phi-Phi's hat trick, by Leif Snellman

- Gordini - Nimble, elegant, ultimately French, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Tazio Nuvolari - Mantua's Great Little Man, by Leif Snellman

- Raymond Sommer - The heart of a lion, by Felix Muelas/Michael Müller

- Luigi Villoresi - Ascari's mentor, by Leif Snellman/Robert Blinkhorn

- Jean-Pierre Wimille - The uncrowned king of the forties, by Mattijs Diepraam

Who?Raymond Sommer, Gigi Villoresi, Louis Chiron, Phi-Phi Etancelin, Eugène Chaboud, Henri Louveau, "Raph", Charles Pozzi et al. What?Maserati 4CL/6CM, Talbot-Lago MC, Delahaye 135CS, et al. Where?Nice and elsewhere When?April 16th to April 30th, 1946 |

Why?

22.04, 1946. V Grand Prix de Nice, Nice, 208.910 km. 4500cc s/c & u/s.

One of the main characteristics of this period is the eagerness to race; it did not matter what or where, as if the drivers were anxious to recover lost ground and lost time; “there was a strong element of 'Carried Forward' about most of drivers, the leading Frenchmen being pre-war veterans Sommer, Wimille, Chiron and Etancelin while the Italians fielded Varzi, Trossi, Taruffi and occasionally Nuvolari himself of the Old Guard plus Farina, Villoresi and Cortese of the more recent pre-war vintage“.

That much is quite correct. The war had been a personal disaster for them, their careers having been brutally interrupted or retarded. Some of the younger ones, such as Farina, Villoresi and Wimille, were just reaching the peak when war erupted. Afterwards, Chiron and Etancelin had to wait one or two years before finding regular employment. That most underrated among the all-time greats, Luigi Fagioli, could resume racing at the top level only in 1950. In Italy and in the Argentine two “new” men were at this time thinking about their uncertain future, the war having postponed the start of their careers by many years. In the second half of the period of which we are telling the story, Ascari and Fangio will come dramatically into the scene; soon followed more quietly by a very young Englishman named Stirling Moss and by a burly Argentinian of gentle disposition, Froilàn Gonzalez. We are going to introduce the personages of our story as soon as they appear on starting grids. Quite a number of them were in Nice already.

“The intervening years seemed to fade like a bad dream the week before Easter week-end. Straw bales lined the road, footbridges were going up, and flags and streamers showed garishly against the blinding white buildings. Motor racing was with us again, correctly enough, in France where it all started over fifty years ago. The scene was Nice, for the Grand Prix, open to racing cars up to 5 litres [?] with or without superchargers. There was also a curtain raiser, the Coupe du [Palais] Casino, open to supercharged racing cars up to 1, 100 c.c. or un-supercharged up to 2,500 c.c.” (John Eason Gibson).

A Grand Prix race had taken place in Nice at the height of the Riviera Summer season from 1932 to 1935. A fashionable crowd had seen only Greats reap the laurel of victory: Chiron (1932, Bugatti), Nuvolari (1933, Maserati, 1935, Alfa Romeo) and Varzi (1934, Alfa Romeo). The politics of supporting only sports car racing carried on by the ACF since 1936 onwards had caused the demise of many French “local” Grands Prix, the GP of Nice among them.

The organisers had judged the attractions of the big sports cars to be insufficient, and so considered the appeal of a Voiturette race, with only Italian and British racing cars. But in 1946 it was a totally different matter. Almost every single “racing” car existing in France turned out in Nice in the week before Easter, helped by the loose “Formula” chosen by the Automobile Club de Nice for their race.

The choice of the date encouraged locals to come. The few lucky ones that could spend in those years the cold months in the warmth of the Mediterranean for the even more fashionable spring season were also undoubtedly there. The setting of the Nice races was in fact the most glamorous possible since the circuit used the Promenade des Anglais, the central boulevard lined on one side by luxury hotels and mansions and by the beach on the other side.

I.1. Sommer & Villoresi

It seems fit to consider these two drivers together in sketching their personalities: they share the same characteristic of being true “racers” as drivers and of demonstrating great generosity as human beings. Today neither are well remembered but they were among the more successful drivers in the period: Sommer scored the highest number of victories in 1946, while Villoresi did the same over the whole of the years from 1946 to 1948. Sommer and Villoresi were the more likely winners of the races when the Alfettas were not entered.

Raymond Sommer (1906-1950) came from a very interesting family. His grandfather Alfred had started a felt-manufacturing industry in the village of Mouzon in the hilly and wooded region of the Ardennes. His son Roger, Raymond’s father, had continued in the family business. Roger was also one of the pioneers of aviation. He built, always in Mouzon, 182 airplanes in the years from 1909 to 1912 but sold the aviation business in 1913 and “returned from aviation to the less exciting but more remunerative business of making felt slippers and such things” not before having taken 3-year old Raymond up in the skies.

Raymond Sommer (1906-1950) came from a very interesting family. His grandfather Alfred had started a felt-manufacturing industry in the village of Mouzon in the hilly and wooded region of the Ardennes. His son Roger, Raymond’s father, had continued in the family business. Roger was also one of the pioneers of aviation. He built, always in Mouzon, 182 airplanes in the years from 1909 to 1912 but sold the aviation business in 1913 and “returned from aviation to the less exciting but more remunerative business of making felt slippers and such things” not before having taken 3-year old Raymond up in the skies.

Raymond’s older brother François took over the family business. He was a pioneer in workers’ participation in the results of the industry. François was a pilot in the French Free Forces during WWII, a big-game hunter and a founder of the Hunting Museum in Paris. Raymond’s younger brother Pierre has continued the family business through a Foundation that still today looks after the development and modernization of the original factory.

Raised in such a family, Raymond grew up non-conformist, independent and dynamic. He had two nicknames: “The wild boar of the Ardennes” and “Raymond, the Lion-Heart” that underlined both his exceptional physical strength and his moral virtues. Strength and stamina were allied with courage, will, tenacity and audacity.

He was one of the most accomplished “amateurs”. He found in racing total enjoyment for the satisfaction of driving, for the passion of speed, for the love that he felt for his talent. “I like gambling, but I do not like money. What else could I gamble then, if not my life?”

He lost races many times after having given everything to win. Crowds loved him: he was spectacular, always driving in the quickest possible way, but with great style, preferring the beauty of a good blow to an insipid good result.

“Battle meant everything for [him]….He spoke of the talents of his fellow drivers in terms of the way they battled, never their string of victories”.1 His independence was his strength: thanks to being well off financially, he always raced his own cars without being bridled by a team. This was also his weak spot: he would have been considered among the all-time Greats if he had elected to drive the better prepared cars that only a works team could provide. In fact he lacked “the ruthlessness that might have pushed his talent into the upper ranks of racing in his day” and he always avoided ambition and greed.

His temper was sometimes difficult, with changing moods. He was an impressive man with an athletic posture: tall, slim, and always dressed in light colours. Taciturn, with steel-blue eyes, a face a bit sad, he looked surly and distant, yet he always behaved as a perfect gentleman, always ready to help with great generosity - either with money, or to give advice or to fight for the just cause. One such instance was finding the bail to free Ferdinand Porsche, who was unjustly imprisoned in France after the war.

After becoming French Champion for the years 1937 and 1939, Sommer was drafted as a private at the beginning of the war and assigned to the not very warrior-minded Signal Corps. He was nonetheless immediately singled out for his courage and destined to dangerous missions. On May 27th, 1940, in the region of Outers-Teene in the Flanders, he shot down “at least” two German aircrafts with his machine-gun as it is mentioned in the Roll of Honour of his Division. Taken prisoner, he was able to escape from a POW camp in acrobatic fashion in 1941. Mention of his wartime achievements cannot be found in most of the many biographical profiles about him: modesty had prevented him from telling the stories publicly.

Sommer would have a scintillating 1946 season followed by a disappointing 1947. Asthma and a nervous depression slowed him down between the second half of 1948 and the first half of 1949. In these years he had often driven for Enzo Ferrari. He parted from him during 1950 on very bad terms: the methods of the autocratic Ferrari had finally displeased him to the point that he had called Ferrari “Al Capone” in an interview. Twelve years later, the extremely difficult Enzo invariantly referred to him as “the dear Sommer” in his book of memoirs. Not a single word – as a matter of fact - can be found in motoring literature and in the contemporary press that is not of praise for him. “Drive your hardest, take the lead early and frighten off the opposition - if possible”, had been Raymond Sommer's credo. Not long before his death, France had awarded him the Cross of the Legion of Honour as “the greatest driver in the country.”

Sommer scored 25 major victories from 1931 to 1950 - 26 if we want to consider the Angoulême international F3 race in 1950. They were one Grande Epreuve - the 1936 GP de l’ACF for sports cars - seven international sports car races, with two 24 hrs of Le Mans, 10 Grands Prix (five major) and seven international F2 races between 1948 and 1950.

In his own words, Luigi "Gigi" Villoresi (1909-1997, pictured at Silverstone in 1948) had started very "… young in small races with the family cars: Lancia Lambda, Ansaldo, Fiat, then, with the first savings, pushed by the mad passion [for racing] I purchased my first "racing car", a beautiful Fiat Balilla Sport. With it, together with my brother Emilio we entered the Mille Miglia in 1933, finishing fifth in class."

In his own words, Luigi "Gigi" Villoresi (1909-1997, pictured at Silverstone in 1948) had started very "… young in small races with the family cars: Lancia Lambda, Ansaldo, Fiat, then, with the first savings, pushed by the mad passion [for racing] I purchased my first "racing car", a beautiful Fiat Balilla Sport. With it, together with my brother Emilio we entered the Mille Miglia in 1933, finishing fifth in class."

He was a gentle and generous man who transformed himself into a hard and spirited driver on the track with the ability to pick up more speed in the last part of a race. Villoresi was a champion for style and courage, a resourceful, intelligent, wily driver, "to the extreme of finesse", as Ferrari put it.

His life was not a lucky one, doomed by tragedy and by a long painful old age, and his career was marked by a series of serious crashes.

Gigi was born in a well-known family in Milan, the grandson of the famous builder of a system of large irrigation canals in the western part of Lombardia, one of which is still called Canale Villoresi. His father, Gaetano, was the head of the company which generated electricity for the city of Milan. Gigi had four brothers and sisters: Rosa who died in a road accident, Eugenio who died young of cancer, Emilio, who shared Gigi’s passion for racing, and another brother who committed suicide.

His generosity as a human being manifested itself in the world of racing when he became the mentor of two young drivers, his younger brother Emilio "Mimì" Villoresi and then Alberto Ascari. He fully dedicated himself to pass on his craft to them and helped them in the key decisions of their careers, feeling no envy for their enormous talent. Emilio, who is said to have possessed more raw talent than Gigi, had become an Alfa Romeo works driver in 1938, when both brothers decided to relinquish their semi-professional status to become full-time professionals in international racing. Gigi went with Maserati instead, and the brothers fought each other with abandon, with Gigi becoming Italian Voiturette Champion in 1938.

Tragedy struck once more on June 20th, 1939. Enzo Ferrari, then Alfa Corse manager, had organized a meeting for Alfa Romeo dealers and customers at Monza for what we would call today a testimonial lucheon. An Alfetta racing car and Emilio were the guests of honor. After lunch, Ferrari asked Emilio to please the visitors with a few laps in the car. Emilio did not feel like doing that as he had had too much to eat and drink, but, at Ferrari’s strong insistence, he yielded. After a few laps, the Alfetta overturned, killing Emilio. Rather hypocritically, the accident was reported as Emilio being killed while testing.

After the war, young Alberto Ascari whom Gigi helped decisively to become one of the all-time Greats took over the role of Emilio in Gigi’s life.2 They were inseparable, always negotiating their contracts with the provision that both had to be signed together. They were also business associates in a Lancia dealership in Milan. In 1949, with Ferrari eagerly seeking their services, Gigi’s generous disposition allowed him to overcome the bad feelings that he had maintained towards Ferrari after the death of Emilio. Bad feelings that had grown when the insurance company had refused to pay – on the basis that Emilio was not fit to drive – and Ferrari did nothing to support the claims of the Villoresi family. Mutual distaste between them was openly acknowledged, ironically providing their relationship with a firm basis.

When tragedy struck once again at Monza, on May 26th, 1955, with Ascari finding his death in a way as stupid as Emilio’s, Villoresi was there. He continued to race however, finding in it the strength to go on living after the end of another very special relationship so unusual in a world where comradeship, rather than true friendship, was the rule.

But Gigi spoke out, finally after Eugenio Castellotti had died, while testing, at Modena on March 14th, 1957. Gigi publicly used the harshest possible words against Ferrari, thinking that Castellotti had died because of yet another of Enzo’s whims, and he was, very likely, correct. "Ferrari is a man who does not know the word ‘thank you’. He believes that a driver owes him everything", he also said. He had never forgiven the man from Maranello and Emilio’s memory had haunted him throughout his life.

It is said that during the war, Villoresi was on board of a ship that was sunk off the Greek coast. After swimming for a whole night, he was rescued by Greek Partisans that were about to shoot him when the British Command intervened. Villoresi was sent to prison camp for the duration of the war.

This adventure had left him distinctively grey-haired.3 but did not prevent him from showing great form in post-war racing. A very bad crash at Geneva in 1950 sent his career into a long decline marred by other crashes, but highlighted by some good performances. Villoresi decided to stop after his fourth severe accident, in Castelfusano near Rome at the end of 1956. His list of victories for the period of this history is impressive; he was overall Italian Champion in 1947 and 1948 and should be remembered as one of the foremost competitors not only of that period, but in the whole history of Italian motor racing.

That some memories were still buried in the deep conscience of the Italian people had become apparent when, after decades of silence,4 news came in about 1990 that Gigi was having a very difficult time in a religious home – in Modena, of all places. His faithful mechanic Cassani continued to care for Villoresi - long after Gigi's business interests had collapsed, his health had broken and life had become so distressing for him -, but he was alone after Cassani had died.

A law exists in Italy to the effect that people, who have distinguished themselves in maintaining the cultural prestige of the country and who incur destitution in old age can be – if not handsomely – very decently supported by the State. This law is difficult to be enforced requiring a unanimous Act of Parliament hence it is seldom used. So far Villoresi has been the only sportsman to profit from it.

Villoresi is one of the drivers who scored the highest number of victories in history. Among them there are 43 major victories in the years from 1937 to 1954: one Grande Epreuve, the 1948 British GP, 22 international GPs, 3 international sports cars races (one Mille Miglia among them, in 1951), 8 pre-war voiturette international races and 9 international F2 races in from 1948 to 1951.

I.2. Chiron & Etancelin

Amongst the French ones, Sommer and Wimille were the more successful drivers of this period, but their elders Chiron and Etancelin also did extremely well.

Louis Chiron (1899-1979, pictured on Jersey in 1947) had not seen GP action since a crash at the Nurburgring in 1936 that had ended his tenure as a Mercedes-Benz works driver. For Anthony Lago, who had given him a car under Faroux’s insistence, he had won the GP de l’ACF in 1937 in a T150C sports car. It was yet another display of the tactical prowess of the "Vieux Renard". Later, he was seen in a Delahaye at Le Mans in 1938. Having flunked a test with Auto Union the same year, the mercurial Louis had disappeared in Monaco – after announcing his retirement from the sport. Indeed, after his win of a lifetime in the GP de l’ACF at Monthléry in 1934, his career "seemed to have plunged from Zenith to Nadir almost overnight".

Louis Chiron (1899-1979, pictured on Jersey in 1947) had not seen GP action since a crash at the Nurburgring in 1936 that had ended his tenure as a Mercedes-Benz works driver. For Anthony Lago, who had given him a car under Faroux’s insistence, he had won the GP de l’ACF in 1937 in a T150C sports car. It was yet another display of the tactical prowess of the "Vieux Renard". Later, he was seen in a Delahaye at Le Mans in 1938. Having flunked a test with Auto Union the same year, the mercurial Louis had disappeared in Monaco – after announcing his retirement from the sport. Indeed, after his win of a lifetime in the GP de l’ACF at Monthléry in 1934, his career "seemed to have plunged from Zenith to Nadir almost overnight".

He dedicated himself to the hobby of "haute cuisine" and sought a more tranquil love life going so far as to marry, with the elegant Edith Bitter, Didi. Racing had made Chiron wealthy, sometimes at the expenses of his personal relationships, but as an older man Louis appeared much more affable and "sympathique", more in accordance with the nickname of "Louis le debonair" which was given to this tough and ambitious man because of his urbane manners and witty chattering, but he was "an authentic Southerner, choleric and a big talker".

At the outbreak of World War II he found himself again in active service – he hold dual citizenship - but with the collapse of France he had to cross over into Switzerland. While there, he helped in the smuggling of downed Allied airman out of neutral Switzerland.

The 40s were going to add other victories to this driver’s list, one of the longest in history. In fact Chiron came back in shining form after the war and was entrusted with the Talbot MC by Anthony Lago. Unfortunately for Louis, Lago retired the car after a few races. Chiron had to use all of his "charme" to get the car back from its new owner, Paul Vallée the boss of Ecurie France, but that did not happened before mid-season 1947.

Chiron is the winner - between 1926 and 1949 - of 29 major races, nine Grandes Epreuves amongst them, together with 17 international GPs and 3 international sports cars races.

Philippe "Phi-Phi" Etancelin (1896-1981), was one of the fiercest competitors in the history of the sport and, very possibly, the most successful pre-war private entrant. Like his compatriot Sommer, he too was helped by a substantial self-made personal fortune from his business as an industrialist in manufacturing mattresses, pillows and bed clothing in goose down.

He was totally different from Chiron as a man and as a driver. At the wheel he was a fiery, fierce fighter who pushed the hardest, with no respect for his machinery about which he knew nothing and which did not interest him in the least. His contemporaries are reported saying that Etancelin would have won much more if he had learned to use his gearbox in a less destructive fashion, but how many more since he won 18 important races for Grand Prix cars? The first signs of which kind of a fearless man he would become were shown very early when as a boy he performed acrobatic feats with the trapeze and walk on a rope accompanied by his older brother who soon would die in the first World War.

Philippe "Phi-Phi" Etancelin (1896-1981), was one of the fiercest competitors in the history of the sport and, very possibly, the most successful pre-war private entrant. Like his compatriot Sommer, he too was helped by a substantial self-made personal fortune from his business as an industrialist in manufacturing mattresses, pillows and bed clothing in goose down.

He was totally different from Chiron as a man and as a driver. At the wheel he was a fiery, fierce fighter who pushed the hardest, with no respect for his machinery about which he knew nothing and which did not interest him in the least. His contemporaries are reported saying that Etancelin would have won much more if he had learned to use his gearbox in a less destructive fashion, but how many more since he won 18 important races for Grand Prix cars? The first signs of which kind of a fearless man he would become were shown very early when as a boy he performed acrobatic feats with the trapeze and walk on a rope accompanied by his older brother who soon would die in the first World War.

As a man, he was very "sympathique",5 a jovial fellow, much more spontaneous than Chiron, an enthusiast, a very warm man, maybe too much at times. He was indeed one of the greatest characters in over a century of French racing history. In 1937, lacking a competitive car, he had announced his retirement, but, as for Chiron, Faroux could not allow such a national talent to be wasted. He suggested that he too should join the Talbot team. Etancelin agreed and Lago was happy to take him over. It was the first works engagement for the independently minded Etancelin who had not been considered for works drives before. The reason for this probably lay in the fact that his business enabled him to stay away for about only six months each year.

Always accompanied to the races by his enthusiastic wife Suzanne,6 he spent the immediate post-war years looking, unsuccessfully, for an adequate mount until he was able to purchase one of the new single-seats Talbot 26C in 1948. In that car the man from Normandy enjoyed a second youth, happily racing until 1954. His driving style was peculiar in the fact that he kept "sawing at the wheel, even on straights". His trademark was a reversed blue cloth cap, which he had worn for his entire racing career. When the use of a crash helmet became compulsory, Etancelin put one of the kind used by bicycle racers in velodromes in top of his usual cap. His hobby was an animal farm in Normandy, his native region, which he never left always living in Rouen.

Etancelin’s score of major victories is 19, between 1927 and 1949. One Grande Epreuve, the 1930 GP de l’ACF, one Le Mans 24hrs race, and 17 international Grand Prix illustrate the palmarès of this great independent driver.

I.3. Chaboud, Louveau, Pozzi & "Raph"

These four racers epitomized the "new" generation of French drivers in the immediate post-war years, although Chaboud and "Raph" had already seen some action before.

Eugène Chaboud (1907-1983), born in Lyon in a family of merchants, would make of commerce – of any kind – his lifelong trade. He soon moved to Paris and quickly became one of the major drivers of the period. A meeting with Jean Tremoulet in 1936 had diverted him from athletics into car racing and he became a typical pre-war Delahaye driver in French sports car racing. He was a Le Mans winner in 1938 with Tremoulet with whom he ran a garage in Paris. The following year he drove Delahayes for Ecurie Francia, which he had founded with his associates Paul and Contet. In 1946 and 1947 he became a full-time professional, gaining respect in the French press, which often put him in the same company with Sommer and Wimille. Chaboud was a talented, reliable, determined and consistent driver and a fighter, who seldom got the chance of driving faster cars than various Delahayes, a marque with which he had a special relationship. In 1946 he became the technical advisor of the new Ecurie France. The team owner Paul Vallée did not treat him very fairly. Despite that, Chaboud was able to become French overall Champion in 1947 with the help of his lifelong friend Charles Pozzi who lent him his fastest car.

The French press, after having previously hailed him, now commented that he was the Champion only because Sommer and Wimille were not particularly interested in gaining it! The problem was that the cold Chaboud was not very "sympathique". In truth Chaboud was a hard and courageous man, very professional, but he had a difficult temper and devoted his life exclusively between his two passions: car racing and gambling. Maurice Louche writes "[Chaboud was] a strange character, difficult to grasp, a bit troubled, gloomy, exerting a strong influence on some driver to the point of manipulating them to use their cars to be able to still compete in the later years of his career". Lying under his overturned Talbot at Le Mans in 1953, he decided to quit, occupying himself with the car trade (and with gambling) until his death.

Chaboud’s major victories are four: one Grande Epreuve, the 1946 Belgian GP for sports cars, one Le Mans 24hrs race in 1938 and two international GPs in 1947.

Henri Louveau (1910-1991), was from from Suresnes, in the Paris Banlieue. He had already driven sporadically for Camérano before the war, although he is considered a genuine post-war driver, the first one whom we encounter in our narrative.

Henri Louveau (1910-1991), was from from Suresnes, in the Paris Banlieue. He had already driven sporadically for Camérano before the war, although he is considered a genuine post-war driver, the first one whom we encounter in our narrative.

Louveau had been a bicycle racer and a test driver for the Fiat concessionaries in Paris and for Fiat and Simca tuner Camérano. While with Fiat he had helped Gordini as a go-between with the factory. Mobilized in 1939, he spent the war with the Algerian Rifles, until the Armistice.

A meeting with Sommer was the turning point of his life. He was befriended by him and, still completely unknown, he was destined to become one of the more active and respected racers of this period by following his advice. He had purchased from the Treasury during the war an old Maserati 6CM, which was confiscated property and which he personally patched up so well that he won with it one of the races of the Bois de Boulogne prologue in 1945. This car was soon substituted by a Scuderia Milan 4CL, obtained through Sommer’s good offices.

Louveau’s looks were those of a tough guy, athletic, handsome and photogenic, so he became very popular with the crowds, their feminine part particularly. He seemed - and sometimes acted - as if he was of irritable disposition, but he was just being outspoken. In truth he was a very generous man.

Louveau was an aggressive but correct driver, who possessed a good team spirit and self-control while racing. As a matter of fact, Louveau ended his short career after two big crashes at Pau and Bern in 1951. He said that this was a life-saving decision since he had realized that he had lost his self-control so he had acquired the tendency to drive beyond his limit. He continued to operate a garage at 52, rue Lecourbe in the 15th district of Paris, specializing in Delages and Maseratis, the two makes of his racing life, and starting a major business in car and truck rentals.

Louveau won only two Grands Prix and one in international sportscar race, but was second in ten times, six of which were Grands Prix. He also scored an important class win at Le Mans.

Charles Pozzi (1909-2001) was another Parisian, an authentic one from Montmartre, born in a family of Northern Italian origin but French enough for his father to die in the Great War in the French Army. His grand father was a sculptor who enjoyed a local fame in the region between Novara and Pavia where a branch of the family is still active in the manufacture of sanitary ceramics. He very soon abandoned studies to become an agricultural engineer to start dealing in cars. Already an agent for Ford in 1932, he then began the trade of his life: selling luxury cars. He had spent the war years in Montauban, in the South of France, setting up a small industry producing coal from wood, then, following his return to Paris, he toured the country collecting cars for resale. He transformed some of these into gasogene-powered vehicles using charcoal as fuel.

Charles Pozzi (1909-2001) was another Parisian, an authentic one from Montmartre, born in a family of Northern Italian origin but French enough for his father to die in the Great War in the French Army. His grand father was a sculptor who enjoyed a local fame in the region between Novara and Pavia where a branch of the family is still active in the manufacture of sanitary ceramics. He very soon abandoned studies to become an agricultural engineer to start dealing in cars. Already an agent for Ford in 1932, he then began the trade of his life: selling luxury cars. He had spent the war years in Montauban, in the South of France, setting up a small industry producing coal from wood, then, following his return to Paris, he toured the country collecting cars for resale. He transformed some of these into gasogene-powered vehicles using charcoal as fuel.

His racing career started in Nice (by lying to Faroux as we shall see) and continued for nine years as an independent driver - parallel to his car dealing - in cars which were always beautifully prepared by his friend and mechanic Marcel Turari.7 During his racing years he enjoyed the advice and friendship of Eugène Chaboud – he had become very likely Chaboud’s only friend – whom he helped to be French Champion for 1947. After having left together Ecurie France, they set up their racing stable, which they named Ecurie Lutetia.

Pozzi was a very consistent driver of great stamina, who gave his best in the most gruelling races as his victory in the difficult Grand Prix de l’ACF of 1949 demonstrates. He suffered no accidents during his career, "maybe because I was not fast enough".

He started trading in Ferraris in 1958, alongside his Rolls Royce and Chrysler dealership, and, by 1968, he was much more successful than the official Ferrari importer, Franco-Britannic, to the extent that Ferrari gave him the exclusive agency for France. During the 70s he fielded a team of sports cars Ferraris too. In this way Pozzi’s name is still today synonymous with Ferrari – and Rolls Royce – in French eyes. Very appropriately Pozzi became the President of the Delahaye Club in the last years of his very long life.

Pozzi is the winner of a Grande Epreuve, the Grand Prix de l’ACF held in 1949 for sports cars. He is the winner also of an international sports car race and three times in the 2L class - in his friend Picard’s Ferrari - in the years 1953 and 1954.

"Raph" (1910-1994, pictured at Albi in 1948) was born in Buenos Aires as Raphaël Béthenod, Count of Montbressieux. His father was a rich silk-maker of the Lyon region and his mother the daughter of the Argentine Minister of Justice. To his impressive name he also added his mother’s family name: de las Casas.

"Raph" (1910-1994, pictured at Albi in 1948) was born in Buenos Aires as Raphaël Béthenod, Count of Montbressieux. His father was a rich silk-maker of the Lyon region and his mother the daughter of the Argentine Minister of Justice. To his impressive name he also added his mother’s family name: de las Casas.

After three years of apprenticeship in cycle car racing in Amilcar, Salmson and Rally, he went into a joint partnership with Sommer to buy a Tipo B Alfa-Romeo for the 1935 season. A "misunderstanding" with Enzo Ferrari led to two tipo B’s appearing and "Raph" had to buy a complete car built in 1932, for 150,000 FF.8 That car was successfully raced during the season and was substituted by a Maserati V8 RI for 1936. "Raph" was so unhappy with it that he sold it in the USA immediately after the Vanderbilt Cup. He then raced Talbot and Delahaye sports cars until the 24hrs race at Le Mans in 1937 where he crashed badly, remaining paralyzed in the legs for six months.

He joined Dusio’s Torino team for 1938, racing Maserati 6CM voiturettes then Ecurie Bleue, racing the Delahayes 145’s (but not the Ecurie Maserati 8CLT because of the war). Demobilized in 1941, he settled in Cannes where he conceived and built a series of about 40 three-wheelers with electrical engines that were called Elecraph 225. In 1946, after a brief stint at American Midget racing in California, he came back to European racing at the wheel of old Maseratis 4CL and 6CM under the Ecurie Naphtra Course banner. He won at Nantes and participated in the first two post-war South American expeditions. "Raph" purchased one of the new Talbot-Lago 26C in 1948, but, after a good second at Comminges, he crashed badly at Albi. He never fully recovered from a fractured skull, suffering for a long time from amnesia.9 In 1949 he raced occasionally a Delahaye and a Gordini. He sold his Talbot in Brazil during his last South American racing trip early in 1950 and quit. Plagued by financial problems, he became handyman and chauffeur to his lifelong friend, the famous French actor and "chansonnier" Maurice Chevalier. After the latter’s death, he worked for an agency renting high-class cars on the French Riviera, and retired in 1984.

This excellent and captivating driver was a modest, unassuming and, of course, "sympathique" man, a great lover of jazz music. He died in old age almost completely forgotten.

"Raph" is the winner of one Grand Prix and of a major sports car race. Curiously he is also the winner of a Midget indoor race at Los Angeles, California, in early 1946, a distinction that not many European drivers – if any – can share.

Which cars did these men drive at Nice?

Quite a few of the racing machinery existing in 1939 had been saved from disaster, destruction and pillage. With the exception of Germany, of course, since German-owned cars and German drivers were banned from international racing until 1950. This, in particular, had the effect of putting a practical end to the career not only of the older drivers like Caracciola and von Brauchitsch, but also the younger ones such as Herrmann Lang and H.P. Müller. It also put into hibernation the technical know-how that had given the supremacy to German cars in pre-war GP racing.

Some of the cars had been successfully hidden either by the factories or by their owners or saved by commercial enterprise such as Reg Parnell had done in England. As for Grand Prix cars, most of the 1500cc voiturettes, Alfa Romeo 158, Maserati and ERAs, were available, Maserati were able, moreover, to build a couple of cars in the bleakest days of the war.

The inheritance of pre-war French sports car racing consisted of some powerful Talbot-Lago’s and a large number of Delahaye’s that could also perform as Grand Prix cars. From the 1938 International Formula, which had seen few cars built outside Germany, only a Talbot-Lago, a Delahaye, a Maserati 8CL and an Alfa Romeo 308 were left in Europe, but most of the motley assortment of older vehicles seen at the Bois de Boulogne would never appear again. Pictured is Louis Chiron in the Talbot MC at Nice in 1946.

The inheritance of pre-war French sports car racing consisted of some powerful Talbot-Lago’s and a large number of Delahaye’s that could also perform as Grand Prix cars. From the 1938 International Formula, which had seen few cars built outside Germany, only a Talbot-Lago, a Delahaye, a Maserati 8CL and an Alfa Romeo 308 were left in Europe, but most of the motley assortment of older vehicles seen at the Bois de Boulogne would never appear again. Pictured is Louis Chiron in the Talbot MC at Nice in 1946.

The biggest problems, instead, were the supply of fuel – everywhere - and of tyres, which were rationed in Italy and France, their inconsistent quality, the obtaining of replacement of parts and the restrictions on currency.

The problems were solved, one-by-one, by the enthusiasm of organizers, entrants and drivers. But new racing cars were either on the drawing boards or announced, and a couple of smaller ones were actually built and raced during the year, as we shall see. The organizers assessed the situation with pragmatism and the races were contested under a kind of Formula Libre with capacity limits which allowed the participation of almost every existing car. Races for less powerful cars were also organised, always keeping in mind the existing material. Starting from September 1946 the new International Formula, valid from 1947, was going to be enforced in some Grand Prix. It only ruled out the 1938 3L supercharged cars, of which very few were left in any case.

I.4. The entrants in Nice

This was going to be the first race in 1946 and the second one held in France since the Bois de Boulogne Prologue, and the first International race after the end of the war. In fact, the Italians were expected and some of them showed up for the race.

Automobiles Talbot-Darracq had unearthed the 1939 Talbot-Lago MC10 "Monoplace Centrale" for the race at the "Bois" in 1945. It was the only true racing car existing in France at the end of the war and it turned out in Nice in mint condition, with the usual distinctive pale blue livery with scarlet numbers, accompanied by Anthony Lago himself, with chief designer Marchetti and head mechanic Angelo. A refreshment flask and tube, full of champagne and water, completed the car for the use of its driver Louis Chiron (v. I.2) who was now 47 years of age.

Two other Talbot-Lagos, of the 150C type,11 were in Nice. One was the 1936 chassis 82933, which was renumbered as 82930 in 1937. It was owned and raced by Pierre Bouillin "Levegh" since mid 1938. "Levegh" (1905-1955),12 was a racing pseudonym already used by his uncle in early 20th century racing. The car had the original sports car bodywork, with cycle-wings removed and was raced in that trim throughout the season. "Levegh" had owned this ex-Le Bègue car since 1938 and sold it to Mouche in 1947 when it was re-bodied as a "biplace-course".

Two other Talbot-Lagos, of the 150C type,11 were in Nice. One was the 1936 chassis 82933, which was renumbered as 82930 in 1937. It was owned and raced by Pierre Bouillin "Levegh" since mid 1938. "Levegh" (1905-1955),12 was a racing pseudonym already used by his uncle in early 20th century racing. The car had the original sports car bodywork, with cycle-wings removed and was raced in that trim throughout the season. "Levegh" had owned this ex-Le Bègue car since 1938 and sold it to Mouche in 1947 when it was re-bodied as a "biplace-course".

"Levegh" was a former ice-hockey player, then the owner of a brush factory in Trie-Château and finally a car dealer in Paris. A proud man, cold and aloof in public where he was never seen smiling, "Levegh" was instead "very agreeable to be with in private". He was a tenacious and consistent driver, capable of being fast when necessary, although very seldom a winner.13 He spent most of a Grand Prix career that lasted until 1951, in Lago’s cars (with the exception of 1947). After that he decided, unfortunately, to make the Le Mans 24hrs race his next challenge. That he went so close to winning in 1952 touched Neubauer’s soft spot. As a consequence "Levegh" turned into the tragic protagonist in the worst ever accident in motor racing when Mercedes-Benz gave him a car for the 1955 race. This is well-known history and, undeservingly, the only reason why "Levegh" is remembered today.

The second T150C was entered and raced by Marcel Balsa (1909-1984). This former motorcycle racer – coming from the deep countryside of Limousin but the owner of a garage at Maisons-Alfort in the Paris suburbs – had been given his first experience of Grand Prix racing in 1939 at Pau and had raised some expectations among the French experts, who were soon going to be disappointed. His honourable career as a gentleman driver at the wheel of his own built BMW and Ford-powered cars lasted well into the 50s. This T150C – chassis 82932 – had been purchased by Balsa from the family of Jean Tremoulet, tragically perished during the war. He was going to sell it soon to Henri Marin, who seldom raced it but had it rebuilt for Balsa to drive. Lack of money unfortunately prevented the development of the car. Balsa had entered for the race in Nice his pre-war Bugatti T51A. A crack in the crankcase discovered on the way south – by road – obliged Balsa to return home to fetch the Talbot. The ill-prepared car did not last very long in the race. Balsa is the winner of two F2 races at Monthléry in the early 50s and of several hill-climbs.

The bulk of French racing cars that survived the war consisted of a substantial number of Delahaye 135CS.14 Before the war they had been used mainly in sports car racing, with a Le Mans victory to their credit and sporadic appearances in GPs, while in 1946/1947 they became a common fixture of GP racing. Without them, starting grids and classifications of the period would have been much thinner.

Practically all of them were re-bodied by 1947 with more or less acceptable dual-purpose (sport and GP) light bodywork. The French invented a splendid word for that: these cars had been, in such a way, "coursifiées". Four of them showed up in Nice.

One (with door and headlights but "coursifiée") was owned and driven by Eugène Chaboud (v. I.3), one of the more important characters of this period. This had a body by Desplats, which set up the style for many future re-bodied 135CSs and a Chausson slanted radiator. Combined research in (AB1) and (DEL) give it the chassis number 47192, an ex-Gérard/Rouault car. It was very possibly the most raced car during 1946/1947.

One (with door and headlights but "coursifiée") was owned and driven by Eugène Chaboud (v. I.3), one of the more important characters of this period. This had a body by Desplats, which set up the style for many future re-bodied 135CSs and a Chausson slanted radiator. Combined research in (AB1) and (DEL) give it the chassis number 47192, an ex-Gérard/Rouault car. It was very possibly the most raced car during 1946/1947.

Chassis number 47193 (always following (AB1) and (DEL) was an ex—Heldé/Contet Ecurie Francia car. It had been purchased by Parisian Henri Trillaud (pictured in 1946) in 1945 and appeared in Nice driven by its owner, who had returned from a German prison camp in time for the Bois de Boulogne prologue. Trillaud was a well-known motorcycle racer who proved to be a racing car driver of good class: "régulier et sûr", consistent and safe. He was a garage owner with shop in 63, Av. de Choisy in Paris 13th district. The car was purchased with the financial help of Paul Valentin, his godfather, uncle and business associate. Great old Albert Divo became an associate too in the part of the business that concerned tuning for high performance cars and a servicec station. Trillaud’s Delahaye featured – in 1946 - a "coursifié" chassis, but an un-modified sports car body.

Chassis number 47193 (always following (AB1) and (DEL) was an ex—Heldé/Contet Ecurie Francia car. It had been purchased by Parisian Henri Trillaud (pictured in 1946) in 1945 and appeared in Nice driven by its owner, who had returned from a German prison camp in time for the Bois de Boulogne prologue. Trillaud was a well-known motorcycle racer who proved to be a racing car driver of good class: "régulier et sûr", consistent and safe. He was a garage owner with shop in 63, Av. de Choisy in Paris 13th district. The car was purchased with the financial help of Paul Valentin, his godfather, uncle and business associate. Great old Albert Divo became an associate too in the part of the business that concerned tuning for high performance cars and a servicec station. Trillaud’s Delahaye featured – in 1946 - a "coursifié" chassis, but an un-modified sports car body.

Belgian driver Emile Cornet (1906-?), whose job was "attaché de presse" for the Grimaldi family - the Princes of Monaco - took the third Delahaye to Nice. He had bought it during the war. Cornet had started racing in 1927 before appearing in the 1945 Bois de Boulogne race. He became Belgian Champion for 1949. He had just arrived in Nice when he received an offer that could not be refused for the car from Parisian car dealer Charles Pozzi (v. I.3). Pozzi, another one of the main characters of the period, after having completed the purchase, had to face a serious problem: he had no previous racing experience and he had to be accepted by the organisers. He persuaded the famous clerk of the course and doyen of French motoring journalists Charles Faroux into letting him start under the pretence of having competed in some pre-war hill-climbs. Faroux was very happy to be talked into it, as with Pozzi there was one more car at the start! The car maintained a very standard sports car appearance during all the season.

The fourth 135CS at Nice belonged to and was driven by Georges Grignard (1905-1977, pictured in 1946). This had been re-bodied by Olivier Lecanu-Deschamps and it looked enough coursifiée. Georges was on his way to become a Talbot-Lago stalwart, after a long wait for a new T26C. His allegiance to Talbot went as far as buying all the stock when the factory was closed down for good in 1959. His garage in Puteaux – where he also prepared his racing cars by himself - was just across from the Talbot factory in Suresnes! He had bought the garage in 1937, soon specializing in the sale of used racing cars. As a 12-year old boy, Grignard had been a volunteer bus-driver in replacement of the ones drafted in the war. In 1924 he started working at Hotchkiss, fist as a mechanic, then as a test-driver. He stayed with them in various capacities until 1937. He also drove a Hotchkiss in the unusual Leningrad-Tiflis-Leningrad race. A consistent driver since the late 20s, he raced in Hotchkiss, Sizaire and in his own Amilcar. He was to become one of the busiest drivers of the post-war period, racing until 1955. Grignard’s driving style called for leaning outside from the cockpit while negatiating a turn, thus showing well his characteristically rolled up sleeves. A big mouth, he was also helped by "an impressive organ of speech". But despite his bursts of voice, Grignard was "a sensitive and warm man, who wept easily". Grignard is the winner of a Grand Prix (GP de Paris 1950), of an important sports car race and of innumerable hill-climbs.

The fourth 135CS at Nice belonged to and was driven by Georges Grignard (1905-1977, pictured in 1946). This had been re-bodied by Olivier Lecanu-Deschamps and it looked enough coursifiée. Georges was on his way to become a Talbot-Lago stalwart, after a long wait for a new T26C. His allegiance to Talbot went as far as buying all the stock when the factory was closed down for good in 1959. His garage in Puteaux – where he also prepared his racing cars by himself - was just across from the Talbot factory in Suresnes! He had bought the garage in 1937, soon specializing in the sale of used racing cars. As a 12-year old boy, Grignard had been a volunteer bus-driver in replacement of the ones drafted in the war. In 1924 he started working at Hotchkiss, fist as a mechanic, then as a test-driver. He stayed with them in various capacities until 1937. He also drove a Hotchkiss in the unusual Leningrad-Tiflis-Leningrad race. A consistent driver since the late 20s, he raced in Hotchkiss, Sizaire and in his own Amilcar. He was to become one of the busiest drivers of the post-war period, racing until 1955. Grignard’s driving style called for leaning outside from the cockpit while negatiating a turn, thus showing well his characteristically rolled up sleeves. A big mouth, he was also helped by "an impressive organ of speech". But despite his bursts of voice, Grignard was "a sensitive and warm man, who wept easily". Grignard is the winner of a Grand Prix (GP de Paris 1950), of an important sports car race and of innumerable hill-climbs.

Maurice Trintignant (b. 1917, pictured in 1946) came with his old Bugatti T35 with T51 engine, wire wheels and Cotal gearbox. It was, supposedly, a modification of the car that his brother Louis was driving, when he was killed at Péronnes in 1933. He had started racing with it at Pau, in 1938, then won twice at Chimay (38/39). The car was kept in a barn during the war, becoming a mice nest and thus originating the nickname of "Pétoulet" – as it is said invented by Wimille – wich was carried by Trintignant during a long and successful career that would last until 1965.15 Bianchi drove another Bugatti, a T51A.16

Maurice Trintignant (b. 1917, pictured in 1946) came with his old Bugatti T35 with T51 engine, wire wheels and Cotal gearbox. It was, supposedly, a modification of the car that his brother Louis was driving, when he was killed at Péronnes in 1933. He had started racing with it at Pau, in 1938, then won twice at Chimay (38/39). The car was kept in a barn during the war, becoming a mice nest and thus originating the nickname of "Pétoulet" – as it is said invented by Wimille – wich was carried by Trintignant during a long and successful career that would last until 1965.15 Bianchi drove another Bugatti, a T51A.16

By far the most numerous cars of a single make in GP grids in 1946/47 were the Maseratis.17 In these first races after the war the array of Maseratis consisted of cars of any age – and quality of the preparation – but by end of the 1946 season the oldest and slowest ones had almost all disappeared.

Among the better prepared in Nice, was the white and blue 4CL, very likely a 1939 car chassis 1566, entered by the Monaco based team of Lucy O’Reilly Schell and driven by Robert "René" Mazaud. Mazaud (1907/46) had been another successful pre-war Delahaye driver. His arrival in Nice had caused turmoil, since the other drivers considered Mazaud’s behaviour during the Nazi occupation ambiguous at least, and they refused to compete with him. Some activities of his, supposedly in support of Benoist's Resistance cellule, were disclosed at once and considered satisfactory.

Today, the all story appears a bit confused and the bashful attitude of the contemporary press does not help. The guilty conscience among French people regarding "collaboration" with the German occupants makes it a touchy subject even today and of course it was a critical one in 1946. Apparently Mazaud was also charged with having made money either from "collaborating" or by helping the Résistance, but the accusation could not be proved. Unfortunately René Mazaud was the first casualty in post-war Grand Prix racing later in the year, at Nantes.

The Schell outfit also entered an old 6CM, chassis 1531 with 1552 4CM engine, and the young scion of the family, Harry Schell (1921-1960), made his racing debut with it.18

Newcomer Henri Louveau, (v. I.3), entered his 6CM, chassis 1537, which by photographic evidence was in pristine form. This was the former Aitken, Gérard car. Louveau had bought during the war in a public sale of confiscated goods – because its French import papers were not in order - and was already victorious in the 1.5L class in its debut at the 1945 Bois de Boulogne race

Another important French Maserati driver-entrant was 'Raph' (Raphael Bethénod de las Casas) (v. I.3). He was behind Ecurie Naphtra Course, which was based in Paris 47, rue Pergolèse, and managed by M.me Denise Depoix. In a press release on April 11th, 1946, Naphtra Course claimed to be in possession of two 4CL's, two 6CM's, one Maserati 8CM and a Alfa Romeo 308. The latter was still forthcoming (see below). The Maseratis are untraceable and it is unlikely that Naphtra Course purchased a more recent 4CL during 1946.19 Dioscoride Lanza,20 a pre-war Italian voiturette driver, was entered as the second driver on the team, but did not arrive in Nice. He was the owner of a 4CL (chassis 1564) and this probably accounts for the second car of that type claimed by the Ecurie. The same release also announced that Naphtra Course was going to Indianapolis in May, a plan that did not materialize.

The last of the "French" Maseratis was a 6CM (c/n 1548, ex-Berg, Loyer) entered and driven by another Parisian garage owner, Roger Dého. Dého (1908/1951) was a builder of Fiat and Simca Specials. A very good friend of Amédée Gordini, he exchanged technical information with him about the tuning of Simca 8 engines.21 He built a series of sports cars and a neat single-seat in the late 1940s.

A local team from Nice, Ecurie Blanche et Noire, was a stable of racing cars owned by the Friderichs, of Bugatti fame. They entered an ancient Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza, chassis 2111040, for journeyman driver Maurice Varet. Varet was a highly reputed mechanic and "metteur à point" (tuner) specializing in Delahaye and Delage, who wanted "to build up for himself a career as a racing driver". Alas, Varet did not succeed in doing so. He seldom got the chance to show his qualities of a determined and consciencious driver, very respectful of his mechanicals. Varet was an authentic Parisian from the 14th district, who had started as a mechanic with Ecurie Bleue in 1937, having been brought there by René Dreyfus. He had a boundless passion for racing and spent years in a feverish quest for a drive, but "…drives are rare for a timid person and Varet belongs to that category of people whose tenacity is not always rewarded…". The always impeccably dressed Varet was also a referee of boxing matches. He is the winner of the race for Grand Prix cars at the Spring meeting in Monthléry in 1947.

A local team from Nice, Ecurie Blanche et Noire, was a stable of racing cars owned by the Friderichs, of Bugatti fame. They entered an ancient Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza, chassis 2111040, for journeyman driver Maurice Varet. Varet was a highly reputed mechanic and "metteur à point" (tuner) specializing in Delahaye and Delage, who wanted "to build up for himself a career as a racing driver". Alas, Varet did not succeed in doing so. He seldom got the chance to show his qualities of a determined and consciencious driver, very respectful of his mechanicals. Varet was an authentic Parisian from the 14th district, who had started as a mechanic with Ecurie Bleue in 1937, having been brought there by René Dreyfus. He had a boundless passion for racing and spent years in a feverish quest for a drive, but "…drives are rare for a timid person and Varet belongs to that category of people whose tenacity is not always rewarded…". The always impeccably dressed Varet was also a referee of boxing matches. He is the winner of the race for Grand Prix cars at the Spring meeting in Monthléry in 1947.

Ecurie Blanche et Noire also had loaned the unique Delahaye 155, the only true GP car ever built by the marque. The car showed up in Nice for technical inspection, but for some reason it was not allowed to race. It figures as a "did not arrive" in the lists. Paul Friderich, Ernest’s son, was supposed to drive it. The ephemeral Ecurie Blanche et Noire disappeared by mid-season, very likely because the poor quality of their obsolete racing equipment could not get hired drives anymore. The Delahaye was then entrusted to Achard.

Raymond Sommer (v. I.1) had a rather old Maserati at his disposal but he got the news that an Alfa Romeo 308 identical to the one that he had raced in 1939 - that had gone to Indianapolis in 1940 and had remained in the USA – was lying in the factory. He had arranged for the car to be brought to Nice, where it arrived accompanied by former chief designer Colombo, team manager Guidotti and head tester Sanesi!22 Hardly a match for the "Silver Arrows", the car would be adequate in the local post-war French races. Jean-Pierre Wimille was indeed in the Sommer’s pit. He was going to race the car successfully in some small meetings during the rest of the season under the Ecurie Naphtra Course banner. Sommer was about to have, in 1946, his best racing season so far, possibly the best of his career.

The Italian contingent, which made the Nice GP the first post-war international race, consisted of four Maseratis entered by the Milan based Scuderia Automobilistica Milan, Milano. The outfit was variously named in entry lists, according to the different country and/or race to which the list referred. Today’s widely accepted abbreviation of Scuderia Milan will be used throughout the narrative, though it was not the original name. Together with his brother Emilio, Arialdo Ruggeri was the team manager. The Scuderia was founded in January 1946 with the backing of a group of enthusiasts and industrialists from Gallarate, which is an industrial town and the hometown of the Ruggeris. It is located in the outskirts of Milan, but their shop was "downtown Milan" at via Mosé Bianchi.

President of the Scuderia was Arnaldo Mazzucchelli and the technical director was professor Mario Speluzzi of the Milan Polytechnic, an expert in supercharging whose ideas had been put into practice mainly on speedboats.

The Ruggeris had built a 1100cc coupe Special for the 1940 Mille Miglia based on Fiat-SIATA components, and a series of new ones – neatly bodied by Bertone in barchetta fashion - was built in 1946 around a Fiat 1100 engine tuned with the help of Speluzzi and of ing. Egidio Arzani, the designer at Volpini. These cars were soon dropped to concentrate on Speluzzi’s experiments with two-stage supercharging for Maserati engines. Which were the 4CL Maseratis actually used in each race by the Scuderia during 1946 is one of the main problems of the period. The chassis used in 1946 were 1568, 1570, 1573, 1579, 1580, and 1581. Besides these, a car, owned and mainly used by Sommer, was a 6CM chassis with a 4CL engine – often called "the older car".

The Ruggeris had built a 1100cc coupe Special for the 1940 Mille Miglia based on Fiat-SIATA components, and a series of new ones – neatly bodied by Bertone in barchetta fashion - was built in 1946 around a Fiat 1100 engine tuned with the help of Speluzzi and of ing. Egidio Arzani, the designer at Volpini. These cars were soon dropped to concentrate on Speluzzi’s experiments with two-stage supercharging for Maserati engines. Which were the 4CL Maseratis actually used in each race by the Scuderia during 1946 is one of the main problems of the period. The chassis used in 1946 were 1568, 1570, 1573, 1579, 1580, and 1581. Besides these, a car, owned and mainly used by Sommer, was a 6CM chassis with a 4CL engine – often called "the older car".  There were in addition the 6CM 1563, the 6CM/4CL chassis 1565 with 4CL engine and the 8CL 3035. One of the reasons for the variety of cars used by the Scuderia is that it enjoyed direct works support this year, and it was therefore considered as a unofficial works team, and rather correctly so. Works support was abruptly ended in March 1947. Three of the cars that arrived in Nice were 4CLs to be driven by Luigi "Gigi" Villoresi (v. I.1), Franco Cortese, Arialdo Ruggeri (pictured on the right in 1946). Likely their chassis were respectively 1570, 1568 and 1573, whereas an older 6CM, chassis 1563, was destined to veteran Philippe "Phi-Phi" Etancelin (v. I.2).

There were in addition the 6CM 1563, the 6CM/4CL chassis 1565 with 4CL engine and the 8CL 3035. One of the reasons for the variety of cars used by the Scuderia is that it enjoyed direct works support this year, and it was therefore considered as a unofficial works team, and rather correctly so. Works support was abruptly ended in March 1947. Three of the cars that arrived in Nice were 4CLs to be driven by Luigi "Gigi" Villoresi (v. I.1), Franco Cortese, Arialdo Ruggeri (pictured on the right in 1946). Likely their chassis were respectively 1570, 1568 and 1573, whereas an older 6CM, chassis 1563, was destined to veteran Philippe "Phi-Phi" Etancelin (v. I.2).

Gigi Villoresi was in splendid form. He was soon to leave Europe to race the Indianapolis 500 Miles in a Maserati 8CL that the factory had entrusted to the care of the Ruggeris. Etancelin was going to be disgusted by the performance of the 6CM, though appearing as usual very quick, as long as it lasted. If he was to be a prospective buyer for the car, the deal did not materialize. Some sources list Ecurie France-Course, Jean Achard’s racing outfit, as the entrant for the car in Nice.

Cortese replaced the great Tazio Nuvolari, who had to stay home at his wife’s side, both devastated by the death of their second son Alberto, precisely ten years after the death of the first son, Giorgio.

Ruggeri (born in 1893), who had already seen action in pre-war Voiturette racing, was an inconsistent racer who at times looked indifferent in his driving. However the importance of the presence of his Scuderia in immediate post-war races cannot be questioned.

In another class was journeyman driver Franco Cortese (1903-1966), who was sparingly used by the Scuderia in 1946. Started in 1926, his career lasted until 1958. Cortese was a driver of great stamina, quick and reliable, who drove one of the widest varieties of racing cars in history. Ever smiling, elegant and "sympathique" he was a first class driver, though he was always considered to be merely a semi-professional. He has the distinction of having been the first Ferrari works driver and the first winner in a Ferrari in 1947. Ferrari asserts that he was the best suited for driving a new car because of his style and technical skills.

In another class was journeyman driver Franco Cortese (1903-1966), who was sparingly used by the Scuderia in 1946. Started in 1926, his career lasted until 1958. Cortese was a driver of great stamina, quick and reliable, who drove one of the widest varieties of racing cars in history. Ever smiling, elegant and "sympathique" he was a first class driver, though he was always considered to be merely a semi-professional. He has the distinction of having been the first Ferrari works driver and the first winner in a Ferrari in 1947. Ferrari asserts that he was the best suited for driving a new car because of his style and technical skills.

Cortese was Italian sports car Champion in ‘37 and ‘38 (Alfa Romeo 2300B) and later the Italian F2 Champion in 1951. He was still capable of winning the Italian 2L sports car Championship in 1956 driving a Ferrari 500 TR. A specialist of the Pescara track, he scored five consecutive victories there between 1934 and 1939 in sports car races. He also won four international voiturette/F2 races in 1938, 1948 and 1950, the Grosvenor Grand Prix in South Africa in 1939 and the Targa Florio in 1951. Cortese finished in more Mille Miglia than any other driver: 14 between ’27 and ’56.

Finally, some sources list Amédée Gordini as a doubtful "did not arrive". In fact he did come to Nice with his new Simca-Gordini T11, 01GC, but only to race in the supporting Coupe du Palais.

I.5. The race

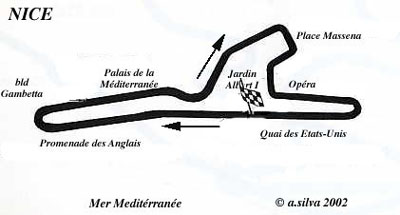

La Promenade des Anglais is a two-lane avenue divided by a kerb with a row of palm trees planted in the middle. The start-finishing line was drawn on the Promenade at the height of the square formed by the Jardin Albert 1er, in the lane along the seashore. The cars would run down that lane until the crossing with the Boulevard Gambetta were they made a U-turn to come back on the opposite side until the Jardin Albert 1er. Here they would go round the square with four sharp corners, one left and two consecutive right ones. On the fourth, instead of coming back to the Promenade with a right turn, a "bump" was added to the circuit in 1946, when the cars would go left onto another divided avenue, the Quai des Etats Unis, which is a continuation of the Promenade in the direction of the Italian border. Another U-turn at the end of the divided lanes in front of the Opera House would bring them back to the end of the lap along the beach. Today one can still walk around the rather wide circuit for all of its approximate length of 3.2 kms.

La Promenade des Anglais is a two-lane avenue divided by a kerb with a row of palm trees planted in the middle. The start-finishing line was drawn on the Promenade at the height of the square formed by the Jardin Albert 1er, in the lane along the seashore. The cars would run down that lane until the crossing with the Boulevard Gambetta were they made a U-turn to come back on the opposite side until the Jardin Albert 1er. Here they would go round the square with four sharp corners, one left and two consecutive right ones. On the fourth, instead of coming back to the Promenade with a right turn, a "bump" was added to the circuit in 1946, when the cars would go left onto another divided avenue, the Quai des Etats Unis, which is a continuation of the Promenade in the direction of the Italian border. Another U-turn at the end of the divided lanes in front of the Opera House would bring them back to the end of the lap along the beach. Today one can still walk around the rather wide circuit for all of its approximate length of 3.2 kms.

It was not a very difficult one, but the memory of Nuvolari going round the sharp Jardin corners as fast as possible was still vivid in every contemporary report.

One wonders how the Nice Municipality – by means of its beautifully named Comité des Fêtes, des Arts et des Sports23 - managed to close the vital Promenade from the beginning of the week before Easter, since we know that Chaboud was already practicing on the circuit on Tuesday. It is likely that the avenue was closed for the afternoon and re-opened in the evening, but we do not know for sure. A quite acceptable field had arrived in Nice for the Grand Prix. Even more than acceptable, if one looks at it more closely: of the 20 starters, 14 had been – or were going to be – the winners of important races. Chiron, Etancelin, Trintignant, Villoresi, Sommer and Chaboud of Grandes Epreuves, and International Grands Prix or at Le Mans, Louveau, "Raph", Grignard and Schell of GP cars races, Cortese of several international voiturette, F2 and sports car races, a Targa Florio among them. In addition, Mazaud had won the important international Antwerp GP for sports cars in 1937 and Pozzi would win the "Grandest" Epreuve of them all, the Grand Prix de l’A.C.F., run for sports cars in 1949, as Sommer had done previously in 1936. It is only debatable whether Balsa’s F2 wins at Monthléry in 1953 were of some significance.

The Italian Scuderia Milan (pictured at Nice in 1946, with from left to right: Ruggeri, Etancelin, Cortese and Villoresi) had arrived in time at the border with France, but Customs had detained the transporters. Creaking and often interrupted long distance telephone calls between Nice, Paris and the border in Ponte San Luigi went on for three days. The cars were finally released following high-level intervention, but they were somewhat late for practice. Despite this, the Maseratis from Milan scored the four best times: Villoresi was two second faster than Cortese, who in turn was one second ahead of Ruggeri, and these three drivers formed the first row. Etancelin, in the oldest Milan Maserati, was about a second slower than Ruggeri, but precisely one second ahead of Chiron who was driving a true GP car, while the Maserati of Mazaud’s was nine second slower than Villoresi! The faster ‘dual-purpose’ former sports cars were the ones of "Levegh" and Chaboud, over ten seconds behind. The other GP car, Sommer’s Alfa Romeo 308, suffered from fuel feed problems and did not register a significant time so Raymond would have to start from way back in the grid.

The Italian Scuderia Milan (pictured at Nice in 1946, with from left to right: Ruggeri, Etancelin, Cortese and Villoresi) had arrived in time at the border with France, but Customs had detained the transporters. Creaking and often interrupted long distance telephone calls between Nice, Paris and the border in Ponte San Luigi went on for three days. The cars were finally released following high-level intervention, but they were somewhat late for practice. Despite this, the Maseratis from Milan scored the four best times: Villoresi was two second faster than Cortese, who in turn was one second ahead of Ruggeri, and these three drivers formed the first row. Etancelin, in the oldest Milan Maserati, was about a second slower than Ruggeri, but precisely one second ahead of Chiron who was driving a true GP car, while the Maserati of Mazaud’s was nine second slower than Villoresi! The faster ‘dual-purpose’ former sports cars were the ones of "Levegh" and Chaboud, over ten seconds behind. The other GP car, Sommer’s Alfa Romeo 308, suffered from fuel feed problems and did not register a significant time so Raymond would have to start from way back in the grid.

Easter Monday arrived, together with 50,000 spectators, in glorious sunny weather. John Eason Gibson is particularly correct when he singles out white as the dominant colour of Nice, blinding in that light. The curtain raiser, the Coupe du Palais de la Méditerranée, had started on time at 1.45pm. By 3.30pm it was smoothly over, with the exception of a crash by René Bonnet who had almost overturned his car in a particularly spectacular fashion that was about to scare off Charles Pozzi from starting in his first race.

By 4.00pm the grid for the GP had been set up, and everything was ready for the start. The start time chosen by the organizers, rather late for the season, would cause a lot of problems to the drivers. The race – approximately 210 kms long – would last for about two hours meaning that the sun was going to be very low on the horizon during the second part of it, creating a dazzling effect for the drivers’ eyes in the section of the circuit along the beach.

Villoresi led the pack into the first hairpin, from Chiron – who had as usual an excellent start - Cortese, Etancelin and Mazaud. Meanwhile Sommer was picking up a lot of positions. Cortese was immediately out of the race, because his blower was not working properly and very soon in the lap Chiron developed plug problems that plagued his race. At the end of the first lap they came by in the order: Villoresi, Etancelin, Mazaud, Chiron, Sommer, Grignard, Chaboud, Ruggeri – who had fumbled his start – Trintignant and "Levegh". By the second lap, Villoresi already had a lead of 14" from Sommer, who had overtaken everyone except the leader with Mazaud, Etancelin, Chiron and Ruggeri following. Between lap 3 and lap 9 Etancelin retired in disgust with magneto problems and Chiron stopped to change plugs. Villoresi set the fastest lap twice in 1’46"9 (108.235 kmh) and 1’45"9 (109.258 kmh), gaining 5 more seconds on Sommer by lap 10. Mazaud and Ruggeri fighting for third followed Raymond. It was clear that Sommer could not catch Villoresi: he looked much slower out of the corners, and it was learned after the race that from early on he had been without first and second gears, which was a particularly severe loss coming out of the two hairpins.

By lap 20, very little had changed with Villoresi leading at an average speed of 108.235 kmh from Sommer, Mazaud, Ruggeri, "Levegh", Chaboud and Grignard. He had set another fastest lap in 1’45"3 (109.880 kmh). Charles Faroux was standing in front of the Opera House taking the times set by the drivers in the section consisting of the third and fourth corners around the Jardin and the second hairpin. The result of his findings was that Villoresi gained about 1" in that section while there was no appreciable difference between the other drivers, another indication of Sommer’s difficulties. "It was as if Nuvolari were there from the brio with which Villoresi was going round the Jardin" says a contemporary report. Sommer had to stop briefly on lap 21 and was passed by Mazaud and Ruggeri, but the unlucky Mazaud had to retire on the following lap with a very noisy gearbox bashfully referred to "ennuis méchaniques".

Villoresi was still leading from Ruggeri on lap 30, despite the fact that Sommer – who had come around in third position – had set the fastest lap of the day in 1’44"8 (110.405 kmh). "Levegh", Chaboud and Grignard were following in that order in their lively fought private race.

Villoresi was still leading from Ruggeri on lap 30, despite the fact that Sommer – who had come around in third position – had set the fastest lap of the day in 1’44"8 (110.405 kmh). "Levegh", Chaboud and Grignard were following in that order in their lively fought private race.

Villoresi re-fuelled on lap 42 and the stop took about 3 minutes! It was the first sign of poor pitwork by the Scuderia, a "quality" that was going to become a constant. Late arrivals at the races, pieces of equipment left behind, lost or misplaced, alcohol and methanol flowing all over from poorly handled cans, were the rule in the Milan pit. This is refreshing since Milanese people are known for always deriding other Italians for their weak organizational skills!

Sommer found himself with a lead of about one minute and a half from Villoresi. Ruggeri had to stop because of that common Maserati complaint, magneto problems. Repairs were long and Cortese took over the wheel. Villoresi was lapping consistently at between 1’45" and 1’46", in the situation that he loved best, the need to pick up speed in the last part of a race. It took him only 9 laps to overtake Sommer, who for once – maybe for the only time in his career – was nursing a car home. By pushing hardest in the last 10 laps, Gigi put Raymond one lap down.

Inspection of the fastest times for each driver shows that Villoresi had been two seconds faster than Mazaud and Cortese, who, in their turn, were half second faster than Ruggeri. Poor great Etancelin had been eight seconds slower than Gigi while Chiron was only five seconds slower in his ailing car. Sommer had had an occasional burst of speed, but he had not been faster than Ruggeri on average. The fastest of the "others" had been "Levegh", 9 and 1/2 seconds slower than Sommer, but he stopped with a broken rear axle, so Chaboud, who was two seconds slower than him, finished in a well deserved third position. The times set by the heavy French former sports cars were not bad indeed.

Villoresi’s average speed had been of 104.385 kmh, slower both than Varzi (106,4 in 1934) and Nuvolari (104.86 in 1935). Sommer’s fastest lap had been 0.4 kmh shy of the record, but it has to be taken into account the fact that the circuit had acquired an extra hairpin in 1946.

It had been a good race in a gorgeous setting and a very auspicious beginning: the re-birth of international racing was – maybe – under way.

The sudden re-admission to racing of Italian drivers and teams after the war – as opposed to the exclusion of Germans – certainly has many different and complex explanations lying outside the domain of sports, the study of which could constitute an interesting problem in political history. The switch of alliances of Italy after the Armistice, Sept. 8th, 1943, the existence of a Resistenza movement and the falling of Italy on the border of the Western side in the division of Europe after the Yalta Conference must have been among the main general political factors. The fact is that re-acceptance of the Italians in international sports had been quick and would culminate in the official participation of Italy in the Olympic games of 1948 in London.

Motor sports were the first to obtain re-admission. This is certainly due to the painstaking work of a group of active and very capable men that were heading the government bodies of the sport in Italy in the post-war years. Most of them were not compromised with Fascism and knew the sport from deep inside. They were pragmatic enough to understand and to exploit quickly the favourable political moment. Also decisive must have been the fact that most racing cars in the country had survived not only the ravages of the war, but also the German plundering and confiscation by the Allies. And that important racing car builders - such as Piero Dusio at first and Enzo Ferrari and Maserati later on - were all set to build new ones.

The Italian government body of the sport had always been the Sporting Commission (CSAI) of the Italian Automobile Club (ACI, RACI – R for Royal - before the war). At the end of 1937, the Fascist government had dissolved the CSAI and substituted it by FASI, a Federation of teams and drivers affiliated with the Italian Olympic Committee. In 1945 the CSAI was resurrected, the FASI was not closed but eventually merged with CSAI in early 1947. Activity had started very soon with a hill climb – downtown Naples, of all places – contested as early as December 19th, 1945.