Final Sommersault at Cadours

Author

- Rémi Paolozzi

Date

- November 21, 2005

Related articles

- Gordini - Nimble, elegant, ultimately French, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Raymond Sommer - The heart of a lion, by Felix Muelas/Michael Müller

Who?Raymond Sommer What?Cooper T12-JAP (followed by a DB, a Gordini and another DB Where?Cadours When?1950 Circuit de Cadours (September 10, 1950) |

|

Why?

In may 2003 I was invited by my friends, Philippe and Nadia, to spend some time in their new home. They had been living near Toulouse and had decided to move on, a bit further from the Ville Rose. “OK” I said, “Where do you live know?” Then Phil laughed and told me that he was sure I had already heard about his new town: “I live in Cadours, off Raymond Sommer street.” Of course I knew Cadours as it is well known as the place where Le Sanglier des Ardennes (the Ardennes wild boar), the French hero, died.

In days gone by, passion accounted for the creation of races (sorry Mr Ecclestone). A team led by Louis Arrivet set up a first race in Cadours on September 18, 1948. It was not called Circuit de Cadours yet. It was just a minor race with twenty local drivers or so. There were only 1.800 spectators. The winner was René Mauriès, from Albi, with his Simca.

The first official Circuit de Cadours took place the following year. Like in 1948, the participants were mainly local drivers except maybe Gerbout, from Paris, who won the race n a rainy day at the wheel of his self-built RG Spéciale-BMW.

Then, in 1950, willing to give this race the fame of a national event, the organizers decided to invite star drivers to race in Cadours. So, in May, they went to Lesparre, not far from Bordeaux, where a Formula 2 race was held.

Sommer, Thépenier, Gerbout and Antonelli were there and agreed to come to Cadours, a small 500-inhabitant town, in September. Later on, when people asked Sommer why he accepted the invitation, he answered that “The organizers of Cadours are so kind.” But many of his friends did not understand why such a great driver wanted to race there. Even Tony Lago worried about it!

On Sunday, September 10th, 14,000 spectators attended the performance of about twenty drivers. The race was split into two 10-lap heats: the first three drivers of each heat were qualified for the final. A second chance was given to two non-qualifiers thanks to a 10-lap repêchage. The final was a 20-lap race.

The entry list was really mixed: there were no less than five DB-Panhard driven by René Simone, Michel Aunaud, Elie Bayol, Marc Azéma and René Bonnet himself. Gordini, the other French constructor, was also there with two T15s for Jean Thépenier and Amédée’s son Aldo.

Another interesting participant was Marcel Balsa at the wheel of a beautiful French F2 car: the Jicey-BMW. This constructor won a minor F2 race in 1949 thanks to the victory of Eugène Martin at the Aix-les-Bains Grand Prix. Roger Gerbout, winner of the Circuit de Cadours a year before, and Jean Galy were registered at the wheel of their own self-built single-seaters: the RG-Lombard and the Galy Spéciale. Whereas Philippe Mas brought his own Simca 8.

There were only three non-French cars: François Antonelli’s “classic” Maserati 6CM plus two Cooper-JAP T12s, one for Sommer, the always spectacular French ace, and the other for Schell, the son of the founders of former Ecurie Bleue: Lucy and Laury. It was the second time that the 1100cc-engined British car appeared in a race. The first time was in late-May at the Circuit du Lac in Aix-les-Bains where Harry Schell gave up during the final because of gearbox failure after winning his qualification heat. Those small 250kg cars could reach 170kph on the Cadours straight thanks to a 92hp engine.

So, despite those “foreign” exceptions, Cadours was definitely a national event, especially since the fourteen participants were all French drivers.

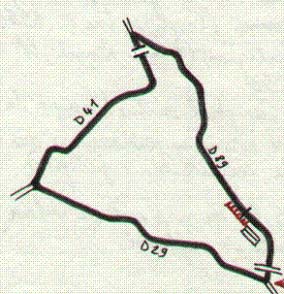

Before the race, Sommer took a car with Mr Tropis, an engineer in charge of the design of the track, to give him some advice in order to improve the track. Those improvements would be taken into account as soon as 1951: new bend design as well as an enlargement of some sections of the track. The result is the current configuration.

Drawing: Michel Marti

On the photographs below you can see remains of the past: the grandstand on the first picture for example… the sand on the last picture is merely the place where the pits were located. I have sorted these photos on the logical order of the track. I had the chance to drive my car on it, a Renault Scénic. The only thing in common with a F1 car is the brand name. But despite the lack of power driving at Cadours gives you a true feeling of what this track was and still is. Moreover I had the chance to drive with my friend Philippe alongside, an amateur racing driver himself. Our first impression was the right one: Cadours is a really nice circuit . A kind of natural circuit, a bit undulating with interesting esses and some bends which are not easy to take efficiently. However, the main difficulty is the circuit's narrowness. Philippe, my Renault and I were alone on the road, which made it easy. But it was undoubtedly difficult to overcome for a competitor, even if Gordinis and Coopers were not the biggest cars of their time. Cadours was a circuit which required talented driver to make a fast lap.

D89 |

D89 |

D89-D29 |

D29 |

D29 |

D29-D41 |

D41 |

D41 straight line |

D41 |

D41-D89 |

D89 |

D89 |

Back to 1950. During qualifying Sommer was fastest thanks to a lap of 2’12” (109.5kph), followed by Bayol (DB-Panhard) and Aldo Gordini (Simca-Gordini T15). Schell was less fortunate: his 1100cc car had not reached Cadours on time, so he had to qualify with his 500cc racer. Thus he was very far on the grid. His car was finally there for the race but his hopes for a win were not very high.

The poleman was logically seen as the favourite for the race. When journalists asked Sommer to give his feeling about the track he answered: “There is a bend one may not miss. The one who will leave the road in this bend will die.”

Nevertheless, after two laps of the first heat Sommer had to retire because of ignition trouble. His only chance to take part in the final and to win the Circuit was to succeed in winning the repêchage or, at worst, to be second. Another guest star, René Bonnet, had to give up following a big crash. He was thrown out of his car but fortunately remained uninjured.

The winner of the heat was Balsa (Jicey-BMW) ahead of Mas (Simca 8), Antonelli (Maserati 6CM) and Thépenier (Simca-Gordini T15). The first three drivers qualified for the final. But unlucky Mas was unable to take part in the final and was replaced by Thépenier.

At the start of the second heat, Bayol took the lead ahead of Gordini. Unfortunately Bayol had to give up after eight laps, two laps before the finish line. It gave Aldo Gordini the opportunity to win the race ahead of Aunaud, Simone (both on DB-Panhard) and Schell who made a splendid race. Hadn’t Schell had logistic trouble at the beginning of the meeting he would have surely climbed the heat podium. Sommer easily won the repêchage ahead of Bayol. Thus, Raymond was back in the race to win.

At the start of the final, Sommer took the lead over Gordini whereas Bayol had to stop at the pits. Sommer was the fastest driver and even performed the FTD in 2’09”, on lap 3! But on lap 8 Sommer went missing. Where was he? Simone was the new leader, ahead of Gordini. It was evident something had happened. Technical failure? An accident? Then Antonelli stopped at the pits to inform that Sommer had violently crashed his car into a tree, after several somersaults. The race went on while a doctor and “Nono”, Sommer’s mechanic, went to the victim who had lost consciousness. His forehead and nose were bleeding. The hero was dead at the age of 44.

The reasons for the accident were not immediately clear. A 3-month close examination of Sommer’s Cooper enabled specialists to eventually identify a steering failure. What Sommer could have done to avoid the accident? Nothing.

Now, who remembers today that René Simone tookhis only single-seater victory on that sad September 10th? He passed the line 22s ahead of Gordini who was followed by Balsa, Antonelli and Aunaud. It is sure that if nothing had happened Cadours would have remained an unknown track among many tracks in France, and the 1950 race would have been an unsignificant race among others.

Of course, Sommer’s death was a big shock for racing fans in France as well as the world. Moreover, Jean-Pierre Wimille, the other great French driver of this era, had died about 19 months before. In a short period of time French racing drivers and fanatics were left without leaders. A memorial to Sommer was erected and inaugurated on September 9, 1951, just before the 3rd Circuit de Cadours. It was financed by a national fund and sculpted by Pessay. On June 2, 1952 Fangio came from Albi to Cadours to meditate at Sommer’s memorial: Raymond had been his friend.

Despite Sommer’s death the Circuit de Cadours was organized almost every year until 1961. Of course, after the Le Mans tragedy of 1955 the security of the tracks had to be improved, much more than before. This surely accounts for the financial difficulties due to necessary investments to protect the spectators and the drivers.

Unfortunately, another tragedy happened in Cadours. In 1958 no car races were organized but motorcycle races instead. And on July 13th Keith Campbell, Australia’s first world motorcycle champion, died at Cadours after crashing out of the race. He was only 26 and had won the 350cc World Championship on a Moto Guzzi the previous year.

After this second tragedy a final car race took place at Cadours in 1961: Jo Siffert won the 12th Circuit de Cadours, at the wheel of a Formula Junior Lotus 20, ahead of thirteen French drivers.

As I said before, the rules to improve security became more restrictive. Organizers failed to finance them and had to give up. Nevertheless, passion was still lively among car fanatics in the area of Cadours. So, almost twenty years after Siffert's victory a first historic race was organized. Since then, every two years, if you go to this lovely little town you will hear the sound of engines roaring in memory of Raymond Sommer, the man whose name is linked to Cadours, eternally.

Cadours record

- 1948: R. Mauriès (F), Simca-Gordini

- 1949: R. Gerbout (F), RG-BMW

- 1950: R. Simone (F), DB-Panhard

- 1951: M. Trintignant (F), Simca-Gordini

- 1952: L. Rosier (F), Ferrari

- 1953: M. Trintignant (F), Gordini

- 1954: J. Behra (F), Gordini

- 1957: Loens (F), Maserati

- 1959: B. De Selincourt (GB), Elva-BMC

- 1961: J. Siffert (CH), Lotus-Ford

Sources

- B. Musqui, Autocollection, August 1987

- Fondation Pierre et François Sommer, Un grand champion de course automobile: Raymond Sommer