Lords of the 'Ring

Author

- Robert Blinkhorn

Date

- 8W Special, May 6, 1999

Related articles

- 1967 Eifelrennen - When snow fell on the 'Ring, by Lorenzo Baer

- 1968 German GP - The class of the field, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- 1970 Eifelrennen - When Rindt became a Ringmeister, by Lorenzo Baer

- Guy Edwards - Grand Prix minnow, Aurora great, by Rainer Nyberg/Mattijs Diepraam

- Harald Ertl - F1's answer to ZZ Top, by Mattijs Diepraam/Philip van Steenbergen

Who?Jackie Stewart What?Matra-Cosworth MS10 Where?Nürburgring When?1968 German GP |

|

Why?

John Young Stewart assuming Rosemeyer's mantle of Nebelmeister, thrashing the opposition by over 4 minutes in torrential conditions. The fight of man and machine against the acts of a God in a particularly foul mood have never been portrayed better than by the epic races through the vulcanic hills of this formerly underdeveloped region. From Schwedenkreuz to Bergwerk, from the Karussel to Pflanzgarten - hell on earth for Grand Prix drivers did exist and it was situated in Western Germany. The classic circuit in between the villages of Adenau and Nürburg had it all - and still has. Today, as a museum track hosting only the annual 24hr Super Production touring car race, it's still a killer, with the Nordschleife - now open to every paying dare-devil - closing only once in a while for the emergency helicopter to fly in and recover a crashed maniac biker to the nearby Cologne hospital. Each time the track reopens, the remaining fans are cramming at the gates to have a go themselves, the two-hour wait having made them even hungrier to meet the ultimate challenge. Are you tempted?

It's official; God loves motor racing.

Why else would he have created the Nürburgring? I don't mean the modern

version; that ersatz track built by a nanny state for the entertainment

of the corporate big cheeses. I mean the real one. The huge 14 mile

blast through the Eifel mountains where every single one of the thousands

of tall pines lining the ribbon of tarmac has a tale to tell about the

good and the great from motor racing's past.

The first Nürburgring is perhaps best known as the place where the titans of pre-war racing built their reputations and where more than a few contenders down the years have paid the ultimate price. In this place, where, like some sleeping serpent, the road winds its way through volcanic peaks and dramatic forests, careers were both made and destroyed. For more than fifty years a win at the 'Ring was the universal measure of a driver. Those who mastered the endless parade of corners that made up the circuit were the best of their age and a victory at the 'Ring was usually the mark of a true champion.

This then, is their story. A story set against the tale of a circuit that only God could have built and only a handful ever truly mastered.

Prior to 1927, Germany had no permanent racing circuit despite the fact its manufacturers were at the forefront of automobile development and, as a nation, Germany already had a strong tradition of success. That success actually began in 1903 when Camille Jenatzy won the Gordon Bennett Trophy in a 90 horsepower Mercedes. As a result of that win Germany was obliged to host the 1904 Gordon Bennett race and did so with the full backing of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The success and popularity of that first event led to the introduction in 1907 of Germany's own Kaiserpreis race series.

Around the same time the suggestion of a permanent testing facility for the German manufacturers was first tabled. There was serious discussion of the idea and a venue in the Eifel mountains was even put forward. In the end though nothing came of the idea and a few years later people had other things on their mind as Europe was plunged into war.

At the end of the conflict Germany was in a perilous state and so it was not until 1921 when the idea re-emerged. To begin with a section of new Autobahn outside Berlin was used for national races and AVUS, as it was known staged, the first German Grand Prix in 1926. In 1925 public rounds around Stuttgart were used to create the Solitude circuit on a temporary basis, although the narrow track was more suitable for motorcycles. Despite these attempts Germany still did not have a dedicated and purpose built track to match the likes of Monza, Brooklands or Montlhéry. Then the Nürburgring was conceived.

The

idea for the track came from a member of the Eifel District Council,

named Dr Otto Creuz. With the support of the motor club ADAC and the

then mayor of Cologne - and future Chancellor of West Germany - Konrad

Adenauer, he convinced the government to invest in the idea. The benefits

of a dedicated test track, along with the need to invest in an economically

depressed region, were obvious and a government grant of 14.1 million

Reichsmarks was approved. Creuz submitted his idea in April 1925 and

within six months, on 27th September that year, the President of the

Rheinland province laid the first foundation stone.

The

idea for the track came from a member of the Eifel District Council,

named Dr Otto Creuz. With the support of the motor club ADAC and the

then mayor of Cologne - and future Chancellor of West Germany - Konrad

Adenauer, he convinced the government to invest in the idea. The benefits

of a dedicated test track, along with the need to invest in an economically

depressed region, were obvious and a government grant of 14.1 million

Reichsmarks was approved. Creuz submitted his idea in April 1925 and

within six months, on 27th September that year, the President of the

Rheinland province laid the first foundation stone.

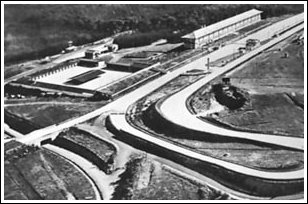

From the very beginning the Nürburgring was an enormous and ambitious project. It was intended to be used as a single 17.6 mile circuit that could also be split into two sections. The Südschleife was a short 4.8 mile section designed for testing and for club racing while the Nordschleife - all 14.2 miles of it - was intended to be showcase of German talent and engineering supremacy. Both sections shared the same start-finish apron that boasted a wide range of facilities. Not only was there a grandstand, capable of seating 2500 people, the designers also included a hotel and a paddock incorporating 70 lock-up garages. The excellent pit complex also incorporated the Continental Tower for use by timekeepers and race officials. Just four years after the circuit was completed, an electronic scoreboard - the world's first - was added to the already impressive list of facilities.

In total the Nordschleife incorporated 172 corners - 84 right-handers and 88 left - and between them those corners included every conceivable combination of radius, camber and gradient. For its entire length the circuit was 6.7 metres wide apart from the start-finish apron which was 20 metres wide and thus created a natural funnel with which to start every race. Almost every twist in the track was designed to test and challenge the best of the best and the true impact of the circuit can only be felt by riding it. Down gradients of one in nine and up one in six hills cars would wind their way along a tortuous road that encompassed no fewer than four villages, while high on the hill, overlooking the entire circuit lay the ruins of Schloss Nürburg, a twelfth-century fortress. In this, its original state, the 'Ring was not a race circuit; it was the setting for an automotive opera that could only have been written by Richard Wagner.

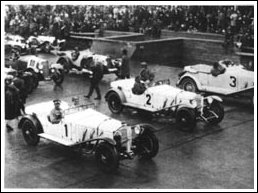

Back in 1926 while more than 2500 labourers were sweating the track into reality a young German driver - Rudolf Caracciola - rocketed into the public eye after winning a rain-soaked first German Grand Prix at AVUS. Within 18 months of that event the Nürburgring was finally ready to host its first event - the Eroffnung-Feier.

The

first race took place on 19th June 1927 and Caracciola set his 'Ring

record rolling with a win. A month later the circuit hosted the German

Grand Prix which was won by Otto Merz when Caracciola's car broke down.

Merz, who had the reputation of being something of a hard man, was a

former chauffeur to Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and had been present

at the 1914 Sarajevo assassination that would go on to trigger World

War One.

The

first race took place on 19th June 1927 and Caracciola set his 'Ring

record rolling with a win. A month later the circuit hosted the German

Grand Prix which was won by Otto Merz when Caracciola's car broke down.

Merz, who had the reputation of being something of a hard man, was a

former chauffeur to Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and had been present

at the 1914 Sarajevo assassination that would go on to trigger World

War One.

In 1928 Caracciola took his revenge and the chequered flag with a fine victory on board a Mercedes-Benz SS. 1929, the last time the full 17.1 mile circuit was used, also saw the first non-German victory when Louis Chiron took his nimble little Bugatti into the winner's enclosure. The 1930 German Grand Prix was cancelled due to the terrible state of the nations economy and a similar fate befell the 1933 race.

In 1931 Caracciola scored a magnificent wet weather victory on board his 7.1 litre SSKL, helped in no small way by Alfred Neubauer's perfectly executed pit-drills. 1932 saw a third win for Rudolf, although this time it was at the wheel of an Alfa Romeo P3.

From 1934 until the coming of the war the Nazi-sponsored Mercedes and Auto Unions dominated the Grand Prix series and the Alfa Romeo, Bugatti and Maserati opposition was simply crushed. In 1934 the race fell to Hans Stuck and the Auto Union team and the following five years saw a series of walkovers that warmed even the coldest Nazi heart. When war finally came the 'Ring had staged a total of eleven Grands Prix and the final score was Mercedes six, Auto Union four with just one upset to distress the Nazi propaganda machine. The year was 1935, the car was a three-year-old Alfa Romeo and the driver was the little Italian - Tazio Nuvolari.

By 1935 the Mercedes and Auto Union teams were proving that with lighter alloys for the bodywork they could use bigger, more powerful engines and yet still remain within the weight limit for the class. As a result the teams arrived with their shiny new machinery. Four Mercedes W25s were produced for Caracciola, Luigi Fagioli, Manfred von Brauchitsch and the new boy Hermann Lang. Ranged against them were the 4.9 litre V12 Auto Unions driven by Bernd Rosemeyer, Hans Stuck, Achille Varzi and Paul Pietsch. In the middle, among a rag-tag mixture of Maserati, ERA and Bugatti privateers, sat the Scuderia Ferrari entered Alfa Romeo P3 of Nuvolari. Tazio's car was little more than an old machine with the engine bored out to 3.2 litres. On a typically overcast German day the race began as expected with the Nazi-sponsored manufacturers fighting among themselves for the important positions. For the first 9 of the 22 laps Nuvolari simply avoided trouble and settled into his stride. He slowly worked his way into second place and on lap 10 he passed Caracciola and moved into the lead. At the halfway stage the leaders began arriving in the pits for fuel and fresh tyres. Aided by the typically slick German pit-stop routines the aristocratic von Brauchitsch was away in just 47 seconds. He was soon followed out by a handful of German cars.

Nuvolari had to sit through a 'typical' Italian stop of over two minutes before he got back onto the track. Angry at the delay, his blood was up and he drove like a total maniac. Over the next few laps he passed Caracciola, Stuck and Fagioli as if they were nothing more than club racers. A later than usual pit-stop by Rosemeyer moved the little Italian back into second place once more. The gap to the race leader - von Brauchitsch - was 1m 27sec with seven laps still remaining. Nuvolari pressed on and the gap came tumbling. First it was 1m 17sec, then 1m 3sec until on lap 21 just thirty seconds separated the two men. Surely not even Tazio could recover such a gap in only one lap? Then the fates stepped in. Aware of the threat posed by Nuvolari, Manfred had begun to push ever harder and seven kilometres to the flag he paid the price for his hard driving. A rear tyre burst and the little Italian simply sailed by to collect the winner's laurels in front of a stunned 300,000 strong German audience including Adolf Hitler.

So confident had they been that a German would win the race the organisers did not even have a copy of the Italian national anthem to play as Nuvolari received his winner's laurels. Luckily Tazio always carried a copy as a lucky charm and the strains of Marcia Reale echoed around the grandstand much to the annoyance of the assembled Nazi hierarchy. It was a triumph of the human virtues of skill and courage over the science of speed and horsepower and is still acknowledged as the finest race of Nuvolari's long and illustrious career. The first legend of the 'Ring had been born.

Another man whose history will always connect to the Nürburgring was Bernd Rosemeyer. Bernd started his motor-racing career on motorcycles and was something of a daredevil. He first hit the headlines in only his second race for the Auto Union team, when during the 1935 Eifelrennen he battled with Caracciola for much of the race. For the 1936 Eifelrennen he came with a car capable of producing 520 bhp and a victory on his mind. During this period grid positions were determined by lot and Rosemeyer began the race from the third row. Almost immediately he was running third behind Caracciola and Nuvolari as a gentle rain began to fall. When Nuvolari made his move on his old adversary Bernd simply followed him and then managed to work his way into the lead. The rain then turned to mist, which in turn coalesced into fog. Everybody slowed down. Everybody except Rosemeyer. Having raced the circuit on numerous occasions during his motorcycling days he knew the place intimately. As a result he began to gain more than 30 seconds a lap and by the end of the race he finished a full two minutes ahead of Nuvolari and six minutes ahead of the lead Mercedes. Incredibly his 72.8mph average was identical to Caracciola's time from the previous year - in a race run in perfect weather. As befitting such a plain-speaking race the Germans called him the Nebelmeister - master of the fog.

Rosemeyer added another win in the 1935 Grand Prix a month later and yet another in the 1937 Eifelrennen. In 1936 he set a new lap record and became the first man to lap the circuit in less than 10 minutes. He missed out on a fourth successive victory in the 1937 Grand Prix when tyre problems relegated him to fourth place. That race was eventually won by Caracciola, although Rosemeyer did register a lap record of 85.62 mph - a record that would stand for 19 years.

The intense Nazi propaganda surrounding the dominance of their teams meant that the 1938 Grand Prix was watched by a crowd of more than 350,000 people. However national pride took another kick in the teeth when - following a pit fire for von Brauchitsch - the race was won by Richard Seaman. That made Seaman the first Briton to win a Grand Prix since Henry Seagrave's victory at Tours in 1923. Before the shadow of war fell across Europe for a second time two more races were staged at the 'Ring and both fell to Mercedes. The Eifelrennen went to Hermann Lang, the European Champion. The final Grand Prix was another wet race and victory once again fell to Rudi Caracciola. It was his last win in an international competition and with it the curtain fell on the first act of the Nürburgring drama.

Perhaps inevitably, the circuit spent the war in military hands but when peace finally returned in 1945 it was handed back to local control. In 1948, after some reconstruction work, the track was once more pressed into service for national races. Initially the occupying forces prevented Germany from competing in international events and so it was not until 1950 that the circuit was used for a Grand Prix race. When the circus finally came back to town the Ferrari pilot Alberto Ascari took over the mantle of Ringmeister with three straight wins (two of them during the Formula 2 years). Giuseppe Farina - the first world champion - made it four in a row for Ferrari in 1953. With the arrival of the 2.5 litre formula Mercedes returned to the world stage. To drive their impressive machinery Mercedes called upon pre-war star Hermann Lang, fellow Germans Karl Kling and Hans Hermann. Alongside them was Juan Manuel Fangio who emerged as the victor in the 1954 Grand Prix. Tragically it was during this race that the 'Ring claimed its first victim of the World Championship era. Onofre Marimon, Fangio's compatriot and protégé, was killed during practise while on the downhill run to Wehrseifen.

In 1956 Fangio repeated the win for Ferrari and in doing so finally broke Rosemeyer's 1937 lap record with an 87.7mph tour. As Nuvolari is often remembered for his 1935 win so Fangio is forever associated with his 1957 visit to the 'Ring. This was the great man's final full season in racing and he was, despite being 47 years-old, at the peak of his form. He arrived in Germany having already won in Buenos Aires, Monte Carlo and at Rouen. On board his works Maserati 250F he had set the pace all season long. As he took to the grid he was surrounded by the Ferrari team of Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins and the Vanwalls of Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks. Every single one of them was championship material and Fangio would have to deliver the race of his career to beat them. That is exactly what he did.

One by one he picked off the opposition and by lap three the Argentine driver was in the lead having knocked a second off the lap record in the process. On laps five, six, eight and ten he repeated the process in his efforts to build up a cushion for himself. On lap 12 he came in for his tyre stop. In a virtual echo of Nuvolari's stop in 1935 the Maserati team got it all wrong and by the time Fangio returned to the track he was almost a full minute behind the Ferraris. On lap 14 he clawed back 12 seconds. Two laps later he reduced the gap by a further 5 seconds. Then, with his tyre bedded in and the car feeling more and more stable he began a sequence of laps that would leave the record books shattered and his earn him the reputation as the best of the best. Four laps later he had torn a full 24 seconds off the lap record and executed the first ever 90mph lap of the 'Ring. It was a stunning display of car control that saw the record falling ever time the Maserati crossed the start-finish line. By lap 20, he was just three seconds adrift of Collins.

He

pressed on once more and caught the Englishman as they left the Nordkurve.

He then nailed Hawthorn and in doing so recovered the lead. He finished

the race 3.6 seconds ahead of Hawthorn and said afterwards 'I did

things I've never done before, and I don't ever want to drive like that

again.'

He

pressed on once more and caught the Englishman as they left the Nordkurve.

He then nailed Hawthorn and in doing so recovered the lead. He finished

the race 3.6 seconds ahead of Hawthorn and said afterwards 'I did

things I've never done before, and I don't ever want to drive like that

again.'

True to his word he never did and that win was the final Grand Prix victory for the great man; who certainly earned his place alongside Caracciola, Nuvolari and Rosemeyer as a true 'Ringmeister'.

When the circus returned to the 'Ring a year later the players had changed a little but this time so had the cars. The British threat to the dominance of what Tony Vandervell called 'those damned red cars' was growing with every race. The Ferrari line-up was still headed by Collins and Hawthorn and they must have experienced déjà vu as they saw Moss storm into the lead from the start. It must have felt even worse as they saw him break Fangio's stunning lap record. Sadly for Moss the fates had decreed that this was not to be his day and he was soon coasting into retirement. That left the honour of the Vanwall team riding on a young dentist from rural England.

Tony Brooks drove the race of his career and soon overhauled the red cars to take the lead. Collins and Hawthorn set off in pursuit but sadly it was destined to end in tragedy. Collins, striving to stay in touch with Brooks lost it on the fast right-hander at Pflanzgarten. He was to die from his injuries. Unable to maintain the pace of the Vanwall Hawthorn, who had witnessed the crash of his closest friend, blew a clutch and was forced to retire. That left Brooks as the first Briton to win a German Grand Prix since Seaman some twenty years earlier. He was followed home by two mid-engined Coopers.

Towards the end of the 1950s the rise of the mid-engined car was gathering pace and the success of Salvadori and Trintignant in this race was a foretaste of how different the grid would look in 1961 when Grand Prix racing returned to the Nordschleife. On that day another classic race would be staged and the status of Ringmeister conferred on another of motor sports favourite sons - Stirling Moss.

At the beginning of the 1.5 litre era the 'shark-nose' Ferrari 156 was the car to beat. By the time they arrived at the 'Ring for the sixth race of the season the little red car had only been beaten once - by Moss at Monaco. The remaining races had been little more than exhibition matches between the American Phil Hill and champion-elect Wolfgang 'Taffy' von Trips. During qualifying Hill smashed the pole record by a massive 14 seconds and in doing so proved the value of a lightweight mid-engined car on a circuit that rewarded handling. The only things standing in the way of another Ferrari walkover were the Porsche 718s of Bonnier and Gurney, Brabham's Cooper (now fitted with the new Climax V8) and an old Lotus 18 with Stirling Moss on board.

Stirling had never won a Grand Epreuve event at the 'Ring but he had proved his credentials with the 1958 Vanwall and with four wins in the 1000km sportscar races for Maserati and Aston Martin, the latter while en route to claiming the 1959 Sportscar World Championship. As in 1958 he was to start the race from the front row. What his opposition didn't know was that Stirling had opted for rain tyres. A heavy shower just before the start convinced Stirling - against the advice of Dunlop - to use these tyres. In order to confuse the competition he had covered over the tell-tale green dots and in doing so set the stage for a game of cat and mouse to rival any cartoon creation.

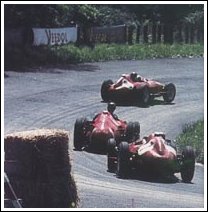

Brabham

made the better start but within a mile he had skidded off handing the

lead to Stirling. Despite being some 30bhp down on the Ferrari competition,

Moss set off into the distance and by lap five he was 15 seconds ahead

of his closest rival. Spurred on by his home crowd von Trips set a new

sub-9 minute record as the road began to dry and brought the gap down

to just 7 seconds. Moss stabilised the gap and in the final third of

the race managed to pull away once more. Aided by rain in the final

laps he finished a full 21 seconds ahead of the competition and once

again Enzo Ferrari was denied his victory at the 'Ring. The win was

the last of Stirling's career although, like his mentor Fangio, he had

marked his passage in style.

Brabham

made the better start but within a mile he had skidded off handing the

lead to Stirling. Despite being some 30bhp down on the Ferrari competition,

Moss set off into the distance and by lap five he was 15 seconds ahead

of his closest rival. Spurred on by his home crowd von Trips set a new

sub-9 minute record as the road began to dry and brought the gap down

to just 7 seconds. Moss stabilised the gap and in the final third of

the race managed to pull away once more. Aided by rain in the final

laps he finished a full 21 seconds ahead of the competition and once

again Enzo Ferrari was denied his victory at the 'Ring. The win was

the last of Stirling's career although, like his mentor Fangio, he had

marked his passage in style.

Four more 1.5 litre races were held at the 'Ring and every one of them was won by a Briton - Graham Hill, John Surtees and Jim Clark. Hill's win in 1962 was watched by a crowd of 360,000 as torrential rain resulted in the slowest race since 1950. Surtees won in '63 and '64 and also scored two sportscar wins here for Ferrari, thus confirming his mastery of the 'Ring. In 1965 Clark, the greatest driver of his era, finally won with typical style. In doing so he produced the first ever 100mph lap of the track, both in qualifying and during the race.

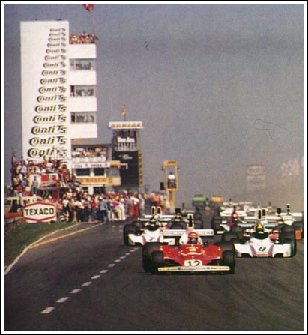

1966

saw a change in formula with the arrival of the 3-litre engines. As

much as Ferrari had been ready in 1961 for the switch to 1.5 litres,

this time it was the turn of the Brabham team. Black

Jack scored a win in 1966 while team-mate Denny

Hulme bagged a victory en-route to his world championship in 1967.

Over the next few years the races were dominated by drivers with girls'

names; Jackie and Jacky. In 1968 the race was staged in the worse possible

weather, but all the rain, wind and fog the Eifel Mountains could muster

did not stop Jackie Stewart from scoring his first win at the place

he called 'The Green Hell'. Speeds may have been reduced to pre-1937

levels but Jackie came home four minutes clear of his nearest rival

and earned the right to stand proud among the Ringmeisters.

1966

saw a change in formula with the arrival of the 3-litre engines. As

much as Ferrari had been ready in 1961 for the switch to 1.5 litres,

this time it was the turn of the Brabham team. Black

Jack scored a win in 1966 while team-mate Denny

Hulme bagged a victory en-route to his world championship in 1967.

Over the next few years the races were dominated by drivers with girls'

names; Jackie and Jacky. In 1968 the race was staged in the worse possible

weather, but all the rain, wind and fog the Eifel Mountains could muster

did not stop Jackie Stewart from scoring his first win at the place

he called 'The Green Hell'. Speeds may have been reduced to pre-1937

levels but Jackie came home four minutes clear of his nearest rival

and earned the right to stand proud among the Ringmeisters.

1969 saw Jacky Ickx became the first man to lap the circuit in under 8 minutes, at an average speed of 110.1mph, although for many his best performance here came in 1967 while competing in the F2 class of that year's German Grand Prix. At the tender age of 22 and on board a 1.6 litre Matra MS5, he practised faster than all except Clark and Hulme and was 21 seconds ahead of the nearest F2 car. Sadly the F2 grid had to line up behind all the F1 entrants but within five laps Jacky was running fifth, having passed 12 full-blown F1 cars on the way. His race ended with suspension failure but his card was marked as a future Ringmeister.

Those early 3-litre races confirmed what had long been feared; the 'Ring was becoming just too dangerous. Like the other great circuits of Reims, Monza and Spa the track had remained unchanged, but the spiralling speeds and a new awareness of the need for greater driver safety meant that the 'Ring would either have to change or die. Grands Prix were becoming more like air shows and organisers knew that they needed more than hedges and chicken-wire fences to stop errant cars from becoming permanent parts of the scenery.

For 1970 the German Grand Prix took up temporary residence at Hockenheim as the 'Ring underwent serious modification. Several corners were re-profiled, bumps were evened out and miles of Armco barriers were used to line the roads. Phil Hill, who had raced the 'old' 'Ring claimed that the place had been emasculated. In some way he was right but of course he was unable to see into the future and witness the sterility that would be visited on Grand Prix circuits during the 1970s and '80s when the likes of Zolder, Fuji and Las Vegas were added to the schedule.

After

a year at Hockenheim the premier German event returned to its true home

for 1971 and the Jacky/Jackie dominance continued. Stewart led Tyrrell

one-twos in 1971 and 1973, while Ickx scored a fine win for Ferrari

in 1972. In 1974 Ferrari won once more with Clay Regazzoni the pilot

while 1975 saw Carlos Reutemann wearing the winner's garland for Brabham.

1975 was also the year that saw the first ever lap in under 7 minutes,

when Niki Lauda got round in 6m 58.6s during practise. Then came 1976

and the final death knell for the Nürburgring.

After

a year at Hockenheim the premier German event returned to its true home

for 1971 and the Jacky/Jackie dominance continued. Stewart led Tyrrell

one-twos in 1971 and 1973, while Ickx scored a fine win for Ferrari

in 1972. In 1974 Ferrari won once more with Clay Regazzoni the pilot

while 1975 saw Carlos Reutemann wearing the winner's garland for Brabham.

1975 was also the year that saw the first ever lap in under 7 minutes,

when Niki Lauda got round in 6m 58.6s during practise. Then came 1976

and the final death knell for the Nürburgring.

The story of the 1976 season would not be out of place in a third-rate novel and is of course too well known to justify re-telling here. Suffice to say that by lap two Lauda had slammed into the cliff face just before Bergwerk. The fire almost cost the Austrian his life but he was destined to return to the cockpit and win two more championship before finally hanging up his helmet. Sadly that fate was not to be shared by the 'Ring. The early 1970s had seen more and more drivers calling for greater safety at the circuit. Lauda's accident proved their worst fears were well-founded and the 'Ring was consigned to the history of Grand Prix racing.

The truth of the matter is that in terms of safety the circuit had a better record than most although it did have its share of fatalities. In Grands Prix meetings alone Viktor Junek (1928), Ernst von Delius (1937), Onofre Marimon (1954), Peter Collins (1958), Carel Godin de Beaufort (1964), John Taylor (1966) and Gerhard Mitter (1969) all lost their lives here.

Despite the loss of the Grand Prix, which moved to the unimaginative Hockenheim, the 'Ring soldiered on for a few more years hosting sportscar and touring car events. Eventually a decision was made to build a new 'Ring. What followed was an act of vandalism that may be soon be repeated at Monza. The old pit complex and grandstand were flattened. Fortunately the old Nordschleife was left intact and thus remains as a monument to the great events it once staged.

The first ever event held on the new track brought out a whole host of vintage Grand Prix machinery. Auto Unions and Mercedes were re-united with the likes of Lang and Fangio for a run round the new circuit. Only one competitive race was staged - it was for Mercedes 190 saloons and was won by a young Brazilian named Ayrton Senna.

During its heyday the 'Ring never claimed to be the fastest circuit, that was the domain of Monza. It was also never the most glamorous setting for motor racing, with that honour belonging to Monaco. It probably does not even have a reputation as a spiritual home of racing which surely belongs to Montlhéry or Brooklands. In fact, many of the drivers hated the circuit. Stewart called it the 'Green Hell' and once said 'I was always relieved when it was time to leave. The only time you felt good thinking about the 'Ring was when you were a long way away, curled up at home in front of a warm fire on a winter night. I never did one more balls-out lap there than I absolutely had to. Any driver who says he loved the 'Ring was either lying, or not driving quickly enough'.

In all of the Grosser Preis events from 1927 to 1976 there were only two races in which a World Champion, or the pre-war equivalent European Champion, did not finish in the top three. In fact in four races, champions filled all three steps of the podium, thus confirming the 'Ring's pedigree as the ultimate test of true ability.

In reality the Nürburgring is actually little more than a piece of

tarmac in an attractive setting. What made it special is the drivers

who tackled, and mastered, the intricacies of a circuit designed to

test their mettle. Astonishing feats of bravery, often tinged with both

madness and sadness make the 'Ring a hallowed place in a way that no

modern circuit could ever be. It was a venue that set apart the greatest

from the great, while making true heroes from everyday champions.

Ben Lovejoy's awesome "Ringer" website