Rear View Mirror & Case History,

Volume 10, No.1

Author

- Don Capps

Date

- May 17, 2012

Download

- RVM Vol 10, No 1 (PDF format, 253KB)

Chasing Down the Dust Bunnies of Automobile Racing History – non semper ea sunt quae videntur – Phaedrus

“Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson | Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman

Indianapolis, we have a problem

Izod IndyCar Series 2012 Historical Record Book, by Steve Shunck and Tim Sullivan, Indianapolis: INDYCAR, 2012.

To begin with, the 2012 edition of the IICS Historical Record Book is pretty much the 2011 edition updated to include information from the 2011 season of the Izod IndyCar Series – or INDYCAR as it seems to be known as of the 2011 season. This means that the problems with the 2011 edition were simply rolled over the current edition.

The book is once again the product of Steve Shunck of IndyCar – or rather, INDYCAR – and Tim Sullivan of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. This, of course, is not all that an unexpected combination given the rather incestuous nature of the IndyCar Series – sorry, INDYCAR – and the Speedway over the decades.

The book, it appears, was done as is at the behest of Randy Bernard, the Chief Executive Officer of the Izod IndyCar Series or INDYCAR, who provided this guidance in an interview in late 2010:

The other one is what we’re doing with our history books. When you talk about all open-wheel drivers – legends and current – the fact that we are going to roll all the statistics up and combine them, so IndyCar statistics will go back for a hundred years, is something I know they appreciate. I think IndyCar fans—CART, IRL, AAA; you name it—will appreciate that too. We have statisticians putting it together right now. They’re combining them as we speak. By the time the new season gets here, you should see a new combined set of IndyCar statistics in our media guide. I think it’s important.

I think if someone breaks one of AJ Foyt’s records, that's huge news. And it’s not being disrespectful to [the legends]… they want it too, they want to see their records recognized for being so great, which they are. And I think that we try to hide that. It was open-wheel racing before the IRL was created, by God, and we need to make sure we go back to that and we combine everything and make sure we honor those legends that have been such a big important part of our history. And if someone breaks one of those records, it’s a huge, huge accomplishment. I think the real open-wheel purist is going to love that. This is long overdue, in my book.1

While Bernard seems to know something about rodeos and maybe even a bit regarding motor racing by now, I get the distinct sense that history was not his major in college.

It is not to damn with faint praise to state that Shunck and Sullivan on the one hand have provided something long overdue and very much appreciated, yet dropped the ball on the other hand. The IICS 2012 Historical Record Book places the basic information for the championship seasons of the various sanctioning bodies in a single work. This sort of compilation has long been needed and the authors deserve great praise for providing a very useful and well done reference work.

The production qualities of the IIRC 2012 Historical Record Book are top notch. It is difficult not to be impressed with its heft, the quality of the pages, and the, yes, the authoritative appearance of the book. As always, however, the devil is in the details.

When I first latched on to a copy of the 2011 edition of the IICS Historical Record Book, the following words on page one – and they are still there in the 2012 edition – popped out at me and made me actually re-read them several times:

This book is the official reference for North American Indy Car racing statistics dating to 1946, and includes records complied by the following sanctioning bodies: American Automobile Association (AAA), United States Auto Club (USAC), Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), Indy Racing League (IRL), Champ Car, and INDYCAR.

The audacity of the statement and how it almost matches that audacity were it not for the minor problem of the 1946 season and how what is found one place is contradicted in another. From 1947 on there are relatively few problems that I could see, and minor ones at that. Generally, they are the sort of problems that are inherent when compiling that much information and then putting it on the printed page. Errors happen and one can easily suppose that they will be weeded out over the next few editions.

There is, unfortunately, a somewhat larger set of problems that need to be addressed. The irony is that in one place problems seem to be addressed and, perhaps, resolved, yet then ignored elsewhere. This dichotomy begins on page six, which addresses “All-Time Indy Car Champions, 1909-2011,” continues on pages seven, “Championships, 1946-2011,” and eight, “All-Time Official Career Race Winners, 1909-2011.”

On page six there is a listing of “Indy Car” champions that begins with 1909. There is an asterisk next the years 1909 through 1919 which leads to this note:

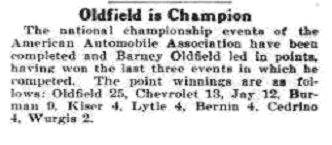

American Automobile Association (AAA) first created a National Track Championship in 1905. It was a series of races from 5 to 10 miles in length with points going to the first three finishing places. Barney Oldfield won most of the races and is considered the champion. However it is believed this championship may have been abandoned as AAA did not recognize it in subsequent years.

Prior to 1916, Motor Age, the leading American automobile journal, selected their pick for the best driver of the year from 1909-1915 and 1919. The following is a list of the Motor Age picks:

1909 – Bert Dingley

1910 – Ralph Mulford

1911 – Harvey Herrick

1912 – Ralph DePalma

1913 – Earl Cooper

1914 – Ralph DePalma

1915 – Earl Cooper

1919 – Eddie Hearne

At the urging of Motor Age, AAA established an official points championship in 1916. The championship was discontinued during war years and not revived again until 1920. Sometime around 1926 or 1927, Val Haresnape, at the time the secretary of the AAA Contest Board, used existing AAA records to reconstruct a championship for the years of 1909 to 1915 and from 1917 to 1920. Unfortunately, records from those early years were sketchy and any points applied by Haresnape had no validity from the original time period. For example, it was a common practice for AAA to penalize drivers with a loss of points as well as money for rules violations. Also, there is disagreement as to which races could legitimately be considered official and therefore count toward the championship. AAA accepted Haresnape’s computations as official from 1927-28 and 1952-55. In 1951, racing historian Russ Catlin convinced AAA to change the 1909 champion from Bert Dingley to George Robertson and the 1920 champion from Gaston Chevrolet to Tommy Milton.

While it is heartening that Messrs Shunck and Sullivan have been paying some attention to the historical issues surrounding the pre-1921 era – more to follow on 1920, of course – and making an effort in an official publication to attempt to correct the long distorted record, they got the title of the song right, but got most of the lyrics wrong. This is in no small part due to at least one of the authors being a statistician and not a historian. There is, contrary to what seems to be the belief in most of the racing world, a significant – if not huge – difference between being a statistician (or something similar) and being an historian. This would strongly suggest that the IICS 2012 Historical Record Book is actually the IICS 2012 Statistical Record Book.

1905

Let me begin with the comments regarding the 1905 season.

American Automobile Association (AAA) first created a National Track Championship in 1905. It was a series of races from 5 to 10 miles in length with points going to the first three finishing places. Barney Oldfield won most of the races and is considered the champion. However it is believed this championship may have been abandoned as AAA did not recognize it in subsequent years.

It was actually known as the “National Motor Car Championship” and the 11 rounds are given below:

10 June / Morris Park, The Bronx

Louis Chevrolet, Fiat

17 June / Charter Oak Park, Hartford

Barney Oldfield, Peerless “Green Dragon”

26 June / Empire City Trotting Track, Yonkers

Louis Chevrolet, Fiat

29 June / Brunot Island Track, Pittsburgh

Louis Chevrolet, Fiat

4 July / Morris Park, The Bronx

Webb Jay, White Steamer “Whistling Billy”

14 August / Glenville Driving Track, Cleveland

Charles Burman, Peerless

19 August / Kenilworth Park, Buffalo

Barney Oldfield, Peerless “Green Dragon”

9 September / Readville Trotting Track, Boston

Barney Oldfield, Peerless “Green Dragon”

18 September / New York State Fair Grounds, Syracuse

Guy Vaughn, Decauville

23 September / Narragansett Park, Cranston

Barney Oldfield, Peerless “Green Dragon”

29 September / Hudson River Driving Park, Poughkeepsie

Barney Oldfield, Peerless “Green Dragon”

| Wins | |

| Barney Oldfield | 5 |

| Louis Chevrolet | 3 |

| Webb Jay | 1 |

| Charles Burman | 1 |

| Guy Vaughn | 1 |

The notion that the championship was “abandoned” is based upon an opinion or observation that seems to have become the accepted view by many. When one begins to study this notion more closely, that the championship was abandoned becomes more difficult to support in light of the following which might suggest otherwise:

2

2

Indeed, I will suggest that the final round of the championship did take place at Poughkeepsie and it was not, therefore, abandoned as often suggested. The daunting part of the is the seeming lack of recognition for the championship in subsequent years. Just how did the American Automobile Association manage to “forget” this championship? Given the lack of much in the way of Racing Board records to work from – as in very, very few to none – regarding issue, one must consider the context of the 1905 season and its Zeitgeist for some idea as to why this amnesia seems to exist.

From what can be gathered, the incoming president of the A.A.A., Elliott C. Lee, and others in the A.A.A. leadership expressed a distinct lack of enthusiasm for automobile racing. Spectator deaths and injuries combined with the highly publicized serious injuries sustained by noted drivers Earl Kiser and Webb Jay and continuing crowd control problems on Long Island during the running of the Vanderbilt Cup did little to endear automobile racing to many within the AAA.

The crowd problems on Long Island were such that the Racing Board was sent a resolution by the leadership of the AAA opposing road racing and recommending that racing be confined only to tracks specially constructed for automobile racing. The number of such tracks in January 1906 was exactly zero.

Another consideration is that during the Winter of 1908-1909, the AAA had just settled its war with the Automobile Club of America and was in the process of reconsidering its role in automobile racing. Although the Manufacturers Contest Association had earlier offered and then withdrew an invitation for the AAA to become the Contest Board of the MCA, the MCA reconsidered and the AAA accepted a renewed offer. The newly formed AAA Contest Board then began sanctioning events by March 1909.

By the time the Racing Board ceased operations and the Contest Board picked up the duties as the national sanctioning organization, the Racing Board had developed a sizeable number of records. A reasonable assumption would be that they transferred to the Contest Board, this being based upon the presence of copies of the Contest Rules prior to 1909 being found in what few pre-1921 records that exist.

Unfortunately, except for any records that might exist in the fabled file cabinets in Indianapolis which were the source for the files found on the microfilm that Gordon White had produced for about three decades ago, little in the way of pre-1909 Racing Board material is available. While one may speculate that the turnover of the membership and staff of the Racing Board – and then, perhaps, the Contest Board, as well – and the contemporary lack of recognition given to the championship at the time allowed the 1905 championship to fade from memory.

Whether or not Barney Oldfield was a factor in the apparent memory loss on the part of the AAA would only be another instance of speculation, although the often stormy and difficult relationship that the AAA and Oldfield experienced over the years might raise a cynical eyebrow or two. That said, the thought does lurk in the back of one’s mind.

Motor Age & the Means-Catlin Championships: 1909-1915, 1917-1919, and 1920

The next part of the note is one that covers quite a bit of mangled history. It also contains the seeds for a major fault with the IICS 2012 Historical Record Book.

Prior to 1916, Motor Age, the leading American automobile journal, selected their pick for the best driver of the year from 1909-1915 and 1919. The following is a list of the Motor Age picks:

1909 – Bert Dingley

1910 – Ralph Mulford

1911 – Harvey Herrick

1912 – Ralph DePalma

1913 – Earl Cooper

1914 – Ralph DePalma

1915 – Earl Cooper

1919 – Eddie Hearne

Beginning with the 1908 season,3 Motor Age began a review of road racing for the season just ended. The initial review was written by C.G. “Chris” Sinsabaugh, who would also most of the subsequent reviews. For the 1908 season, no driver was singled out for attention. In the 1909 review,4 did single out several American drivers, with Bert Dingley and George Robertson being pointed to as being the top two during the season:

In the race for supremacy it is hard to pick one who is head and shoulders above the rest, as was, the case last year, when Strang had them all beaten in number of races won. However, it would seem as if Bert Dingley and George Robertson are entitled to the most credit for their fine work. Perhaps, if anything, Dingley should be favored.5

In subsequent years, this endorsement of Dingley would be hardened into a selection, if you will, rather than a suggestion.

In 1910, The Horseless Age joined Motor Age in reviewing racing from the past season,6 but did not name a “champion” or otherwise single out an individual driver for such recognition.

For the 1911 season, there were now three publications7 providing reviews of the season, but only one, Motor Age, named a “champion” for the season, in this case the rather obscure Harvey Herrick – a choice endorsed by Fred Wagner, no less.8

For 1912, the Motor Age9 review gave its choice in the following words, which should be read carefully: “Road racing in 1912 developed in Ralph de Palma the champion driver of the year so far as American sport is concerned.”10 Perhaps, it is time to point out that the selection being made by Sinsabaugh for Motor Age is for the best driver each season as far as road racing is concerned. Track races are not considered in Sinsabaugh’s reckoning, something that is usually either not known or simply overlooked or ignored. Hopefully, this should provide a bit of missing perspective to the Motor Age selections: they only reflect the road racing efforts of the driver selected and not necessarily his overall merit that season.

The use of road racing results only for the Motor Age selection carries over to the 1913 season as well,11 with The Horseless Age joining Motor Age in reviewing only the road races of the season.12

In 1914, Motor Age once again focused on road racing in its end of season review,13 while The Horseless Age included both road and speedway events in its review.14 The Horseless Age did suggest that while “[t]here is no accurate method of figuring the standing of the standing of the various drivers that participated in the various road and speedway races on a percentage basis…”15 this did not deter it from proclaiming: “De Palma the Champion on Roads.”16

It is, perhaps, MoToR,17 that truly pushes the envelope with an its approach to determining the American road racing champion. It used a points-scoring scheme to determine the champion, what is known as the “Mason System,” named for the person who devised it, Harold T. Mason.

Mason created a rather interesting and unusual scoring system18 to determine the 1914 season’s road racing champion for the United States:

| 10 points | = | first place |

| 6 points | = | second place |

| 4 points | = | third place |

| 3 points | = | fourth place |

| 2 points | = | fifth place |

| 1 point | = | sixth place |

| 7/8 point | = | seventh place |

| ¾ point | = | eighth place |

| 5/8 point | = | ninth place |

| ½ point | = | 10th, 11th, or 12th place |

| ¼ point | = | 13th, 14th, or 15th place |

| 1/8 point | = | 16th thru 20th place |

| - 1 point | = | one point is deducted for each race started without finishing |

The top 10 positions in the Mason ranking of American drivers for the 1914 season were computed as follows:

| 1st | 99 5/8 points | Ralph de Palma |

| 2nd | 80 points | Ralph Mulford |

| 3rd | 72 5/8 points | Bert Dingley |

| 4th | 66 points | Hughie Hughes |

| 5th | 55 points | George Robertson |

| 6th | 52 points | Earl Cooper |

| 7th | 48 points | Charles Merz |

| 8th | 47 points | Lewis Strang |

| 9th | 43 points | Harris Herrick |

| 10th | 36 1/8 points | Louis Nikrent |

Mason did not include a listing of events to accompany his article – or, at least, MoToR did not print it – so one must rely on others for these events and placings. Motor Age19 lists nine events in its listing of American road races during the 1914 season:

| 26 February | Santa Monica / William K. Vanderbilt, Jr. Cup |

| 28 February | Santa Monica / Grand Prize for the Gold Cup of the Automobile Club of America |

| 4 July | Visalia Road Race |

| 21 August | Elgin / Chicago Automobile Club Trophy |

| 22 August | Elgin / Elgin National Trophy |

| 16 September | Spokane to Walla Walla Road Race |

| 8-9 November | El Paso to Phoenix Race |

| 9-11 November | Los Angeles to Phoenix Desert Race |

| 26 November | Corona Road Race |

The Horseless Age20 review listed these road races for the 1914 season:

| 26 February | Santa Monica / William K. Vanderbilt, Jr. Cup |

| 28 February | Santa Monica / Grand Prize for the Gold Cup of the Automobile Club of America |

| 18 April | Merced Road Race |

| 23 May | Hanford Road Race |

| 3 July | Tacoma / Intercity Trophy |

| 3 July | Tacoma / Potlatch Trophy |

| 4 July | Tacoma / Montamarathon Trophy |

| 4 July | Visalia Road Race |

| 6 July | Prescott / “Outer Loop” Road Race |

| 21 August | Elgin / Chicago Automobile Club Trophy |

| 22 August | Elgin / Elgin National Trophy |

| 8-9 November | El Paso to Phoenix Road race |

| 9-11 November | Los Angeles to Phoenix Desert Race |

| 26 November | Corona Road Race |

What is interesting in comparing these lists and then with the Mason scores is that Oldfield is not credited with a first place in the scoring tally, nor is Hugh Miller, the winner of the El Paso to Phoenix race. Relatively minor item, but one of those that presents itself when one does a bit of digging.

The 1915 season, the year before the Contest Board created the inaugural national championship, was addressed by no less than four articles in three automotive publications. The Horseless Age review21 used the Mason System to determine the champion, but apparently omitted the explanations for points awarded for 11th and 12th, ½ point, as well as ¼ point, 13th thru 15th, 1/8 point, 16th thru 20th, and that a point was deducted for not finishing a race. This was apparently due to Shaw modifying the Mason System to deduct a point for each time a drover was unplaced in a race he started.

The Horseless Age review provided the overall standings for the season as well as the leaders for both the road races and the speedway events. Here are the overall standings:22

| 1st | 51 points | Earl Cooper |

| 2nd | 38 points | Gil Anderson |

| 2nd | 38 points | Eddie O’Donnell |

| 4th | 33 points | Dario Resta |

| 5th | 31 points | Eddie Rickenbacher |

| 6th | 28 5/8 points | Barney Oldfield |

| 7th | 21 points | Ralph de Palma |

| 8th | 19 points | Glover Ruckstell |

| 9th | 16 ¾ points | Bob Burman |

| 10th | 15 points | Eddie Pullen |

| 11th | 5 points | Ralph Mulford |

The standings for the road racing events were:

| 1st | 24 points | Earl Cooper | |

| 2nd | 23 7/8 points | Barney Oldfield | |

| 3rd | 20 points | Dario Resta | |

| 4th | 17 points | Gil Anderson | |

| 5th | 14 points | Eddie O’Donnell |

An interesting aspect of the road racing scores is that the Rickenbacher score of the road races was a -1, this being despite a fourth place finish (Tucson) which was apparently balanced against being unplaced for four road races. This resulted in a negative score, -1, for Rickenbacher. This how the overall score for Rickenbacher ends up being less than the score he earned for the speedway events.

The speedway standings were:

| 1st | 32 points | Eddie Rickenbacher | |

| 2nd | 27 points | Earl Cooper | |

| 3rd | 24 points | Eddie O’Donnell | |

| 4th | 21 points | Gil Anderson | |

| 5th | 17 points | Ralph de Palma | |

| 6th | 14 points | Glover Ruckstell |

The MoToR season review23 noted that there were three drivers “who have done almost equally well – Earl Cooper, Barney Oldfield, and Dario Resta.” Although praise and consideration is accorded to all three, it is Cooper who finally gets the nod.

Motor Age had not one, but two season reviews for 1915. The first review considered the road races of the season,24 while the second25 addressed the speedway events. It is the latter review that was a departure for Motor Age, whose previous season reviews were focused on road races.

For the Motor Age review of the speedway events, the author created not only a points system and also a two-tiered “championship” for the speedways. The points system was quite simple:

| 1st place | = | 6 points |

| 2nd place | = | 5 points |

| 3rd place | = | 4 points |

| 4th place | = | 3 points |

| 5th place | = | 2 points |

| 6th place | = | 1 point |

The author then split the speedway events in two divisions: “major” and “minor.” The major speedway division included the following tracks:

Indianapolis / Indianapolis Motor Speedway

Chicago / Speedway Park

Brooklyn / Sheepshead Bay Speedway

Fort Snelling / Twin City Speedway

The minor division included these tracks:

Omaha / Omaha Auto Speedway

Des Moines / Des Moines Speedway

Providence / Narragansett Park Speedway

Sioux City / Sioux City Speedway

Tacoma / Tacoma Speedway

The champion for the “major” division was Gil Anderson with 16 points, followed by Earl Cooper with 12 points, and Dario Resta with 11 points. The champion for the “minor” division was Eddie Rickenbacher with 18 points. Invitational events were not included in the calculations.

What one does not find anywhere in the contemporary literature is a “national championship” created and sanctioned by the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, which the authors of the IICS 2012 Historical Record Book, unlike far too many others, recognize and accept. Then there is this statement in the IICS 2012 Historical Record Book which, in light of the foregoing discussion, certainly does raise an eyebrow – or, perhaps, even both:

At the urging of Motor Age, AAA established an official points championship in 1916.

Unless the authors know something that has escaped others, this statement is a rather difficult to accept, especially when it states that it was “[a]t the urging of Motor Age….” that the Contest Board created a national championship in 1916. If the authors meant to imply that C.G. Sinsabaugh, who had written the road racing season reviews for Motor Age since 1908 and selected a “champion” since 1909, was behind the move to motivate and urge the Contest Board to create the national championship for 1916, he had moved to MoToR by 1915 and was no longer at Motor Age.

Legend has had for many years that it was Eddie Edenburn of the Detroit News who helped draw up the first points schedule and generally push the Contest Board towards creating a national championship. There might even be some elements of truth in the involvement of Edenburn in the creation of the national championship in 1916. However, the lack of the documents that might clearly lay out what led the Contest Board to its decision is lacking, therefore, it is something of, if not a mystery, and unknown. However, what does seem crystal clear is that there is nothing in the Motor Age review of the 1916 season26 that would lead to the assertion that it was the urging of Motor Age that made the difference.

Let us examine the next statement contained in the note:

The championship was discontinued during war years and not revived again until 1920. Sometime around 1926 or 1927, Val Haresnape, at the time the secretary of the AAA Contest Board, used existing AAA records to reconstruct a championship for the years of 1909 to 1915 and from 1917 to 1920. Unfortunately, records from those early years were sketchy and any points applied by Haresnape had no validity from the original time period. For example, it was a common practice for AAA to penalize drivers with a loss of points as well as money for rules violations. Also, there is disagreement as to which races could legitimately be considered official and therefore count toward the championship. AAA accepted Haresnape’s computations as official from 1927-28 and 1952-55. In 1951, racing historian Russ Catlin convinced AAA to change the 1909 champion from Bert Dingley to George Robertson and the 1920 champion from Gaston Chevrolet to Tommy Milton.

Give the authors credit for getting most of this correct. Arthur Means, an employee of the Contest Board, did, indeed, create a set of notional “national championships” that covered the years 1909 – 1915 and 1917 – 1919, as well as providing a different champion for the 1920 season. The earliest example of his work that I have been able to find appeared in late 192727 in conjunction with the 1927 championship. There is a paragraph which multiple champions are discussed, which by winning his second championship, now includes Peter DePaolo:

| 1911, 1918 | Ralph Mulford |

| 1912, 1914 | Ralph DePalma |

| 1913, 1915, 1917 | Earl Cooper |

| 1920, 1921 | Tommy Milton |

| 1922, 1924 | Jimmy Murphy |

| 1925, 1927 | Peter DePaolo |

At a later date, the sentence, “DePaolo thus becomes the sixth member of a very famous sextet of illustrious drivers to achieve the coveted title in more than one year,” is changed by someone using a pen or pencil by striking out “sixth” and replacing it by “fifth” as well as “quintet” replacing “sextet.” In addition, Milton is struck through and there is the notation “Gaston Chevrolet” written to the side. There is, unfortunately, nothing to indicate the date that this was done.

This sentence, “For example, it was a common practice for AAA to penalize drivers with a loss of points as well as money for rules violations,” does not, to the very best of our knowledge, have any basis in fact since there is no indication in any of the records or announcements or press releases regarding penalties being meted out to drivers or owners that involved the loss of points as part of that punishment. That, of course, begs the question as to exactly what points would have been forfeited given that there were no championships to award points to begin with.

This sentence, “Also, there is disagreement as to which races could legitimately be considered official and therefore count toward the championship,” is part of the conundrum that Shunck and Sullivan create and which serves to undercut any effort on their part to seemingly correct the record that has been so mangled and distorted over the years. While they might seem to know the tune, they have no idea as to the words.

Harsh words perhaps, but, unfortunately, all too true. That the authors make what seems to be an effort to set the record straight and then continue as if what they wrote in one place has no bearing in another is quite exasperating and, yes, irritating. Despite writing this, “AAA accepted Haresnape’s computations28 as official from 1927-28 and 1952-55. In 1951, racing historian Russ Catlin convinced AAA to change the 1909 champion from Bert Dingley to George Robertson and the 1920 champion from Gaston Chevrolet to Tommy Milton,” clearly implying that something was amiss, they then proceed to accept these errors as fact.

That there are events and seasons from non-existent, non-concurrent “championships” being included in the “all-time” lists compiled by Shunck and Sullivan is nothing less than dismaying given that it purports to be “the official reference for North American Indy car racing statistics.” Although the authors caveat this by adding “dating to 1946,” they still get it wrong.

And, then, it gets worse….

1920

The authors have, alas and alack, fallen hook, line, and sinker for a canard has been perpetuated by first Arthur Means, then Russ Catlin, and, finally, Bob Russo:29

AAA had two different listings for the 1920 season. At the start of the year, 11 races were listed as counting toward the championship, but at the end of the season, AAA determined the championship to be based on the results of five races giving Gaston Chevrolet the championship. These results were considered official by AAA from 1920-26 and 1929-51. The 11-race championship was first recognized in 1926 with Tommy Milton as champion and was considered official for 1927 and from 1952 to 1955, the final year that AAA sanctioned auto racing.

Noted automotive historian John Glenn Printz provided a scathing two-part rebuttal30 the Russo article and the role that Russ Catlin played in both the distortion of the 1920 championship and the entire pre-1921 history of what might now be anachronistically referred to as “North American Indy car” history.

In essence, Russo parroted what he was told by Russ Catlin – and, it seems, managed to “improve” the tale in retelling. In each of the five events that counted towards the 1920 championship, there is nothing that can be found in the contemporary materials to indicate that the drivers and the press were not fully aware as to which events counted towards the championship and those that did not. Nor is there any indication in the season review appearing in MoToR31 to indicate that anything was amiss. Had Milton been the victim of the sort of conspiracy to commit the sort larceny that Russo – and Catlin – state there seems to be no contemporary evidence of it. That there are numerous articles in contemporary newspapers and magazines clearly stating the championship standings after each event would either indicate that what Russo wrote was a total fabrication – nice way of saying lie, or that there was a conspiracy of enormous proportions that occurred, one that would truly shock historians of the era.

Needless to say, everything points to the Russo article being flat wrong in every respect. Therefore, why does the note actually support what is simply not true and, therefore, once again distort and continue the pernicious subverting of history?

1946

The national championship for 1946 was an oddity in that its inclusion of virtually every Big Car event held in the East – and a few in the Midwest, was included in the championship:

AAA in 1946 had an original schedule which included not only the six traditional championship races as listed by recent historians but numerous other sprint car races on tracks of short length (less than 1-mile) and duration (mostly 15-20 laps). Ted Horn won the championship based not only on the six races that have been traditionally listed but also the one with all of the races. In annual meetings in December, 1946, AAA abandoned the counting of the sprint car races in the championship for 1947. The following is the 1946 top-ten in points as listed in an AAA bulletin as of December 31, 1946:

1. Ted Horn – 2,448

2. George Robson – 1,544

3. Emil Andres – 1,348

4. Bill Holland – 1,280.6

5. Tommy Hinnershitz – 896.8

6. Walt Ader – 850

7. Jimmy Jackson – 800

8. Joie Chitwood – 693

9. Rex Mays – 613

10. Duke Dismore – 454

The reason for the inclusion of so many events was the fear on the part of the Contest Board in the latter part or 1945 and early 1946 that there may not enough cars for the championship. Needless to say, as the season began and progressed it was clear that this fear was misplaced and there were sufficient cars for the championship. However, the Contest Board did not change its criteria for the championship and the number of events in the championship ended up being well over seventy.

It seems that almost immediately that the Contest Board began to indulge in a bit of historical revisionism that essentially meant that it suffered a bout of amnesia and forgot about all those Big Car – or Sprint Car, events that formed the vast bulk of the 1946 championship events. That Ted Horn would have won the championship regardless of whether or not the Sprint Car events were included or not, simply facilitated the Contest Board’s doing so.

Of course, the Contest Board would suffer another bout of mental confusion in a few years when it fell under the spell of the charlatan Russ Catlin and then proceeded to bollix its own history to the point where any attempt to disprove the lies are met with shock and dismay that someone would dare to revise “history” while being totally unaware that the “history” they are defending is actually the revision and, sadly, mythology and fraud.

Here, for Messrs Shunck and Sullivan, is a listing of the 1946 AAA National Championship events taken from the Sanction Records of the Contest Board. It gives the date, location, venue, and distance of each main event as well as the winner of the Main Event as well as the entrant and Car Name. The listing includes the race dates that were not held for various reasons for the sake of completeness.

31 March / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway (Sanction No. 3961), Mike Benton Sweepstakes, 20 miles.

Jimmie Wilburn, (Jimmie Wilburn) Morgan Offenhauser

This was an invitational event and did not count towards the national championship.

14 April / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway (Sanction No. 3962), 15 miles

Walt Ader, (Ted Horn Enterprises) Schrader Offenhauser

28 April / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway (Sanction No. 3963), 15 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

5 May / Trenton, New Jersey State Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3964), 20 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Fred Peters) Peters Offenhauser

5 May / Dayton, Dayton Speedway (Sanction No. 3965)

Initially postponed to 9 June due to track construction delays and then cancelled.

12 May / Winchester, Funk’s Speedway

Rain, not held.

19 May / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway (Sanction No. 3967), 15 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Fred Peters) Peters Offenhauser

26 May / Reading, Reading Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3966), 12.5 miles

Walt Ader, (Ted Horn Enterprises) Schrader Offenhauser

26 May / Winchester, Funk’s Speedway (Sanction No. 3968), 15 miles

Bus Wilbert, (Charles Engle) Engle Offenhauser

26 May / Langhorne, Babcock’s Langhorne Speedway (Sanction No. 3969)

Cancelled

30 May 1946/ Indianapolis Motor Speedway, International 500 Mile Sweepstakes (Sanction No. 3960)

George Robson, (Thorne Engineering) Thorne Sparks

30 May / Trenton, New Jersey State Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3970), 20 miles

Johnny Shackleford, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

30 May / Altamont, Tri-County Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3971), 15 miles

Bumpy Bumpus, (Bumpy Bumpus) Bagley Hal

2 June / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway (Sanction No. 3973), 25 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

9 June / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway (Sanction No. 3974), 15 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

9 June / Thompson, Thompson Speedway (Sanction No. 3972), 15 miles

Oscar Ridion, (Oscar Ridion)

This event moved from its original 2 June date to 9 June.

16 June / Flemington, Hunterdon County Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3975), 12.5 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

16 June / Indianapolis, Indiana State Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3976)

Cancelled

23 June / Greensboro, Central Carolina Fairgrounds, 12.5 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

23 June / Thompson, Thompson Speedway (Sanction No. 3977), 12.5 miles

Oscar Ridion

23 June / Dayton, Dayton Speedway, 15 miles

Elbert Booker, (Lawrence Jewell) Jewell Hal

29 June / Dayton, Dayton Speedway, 10 miles

Bus Wilbert, (Charley Engle) Engle Offenhauser

30 June / Langhorne, Babcock’s Langhorne Speedway (Sanction No. 3979), 100 miles

Rex Mays, (Bowes Racing) Bowes/Stevens Bowes/Winfield

30 June / Thompson, Thompson Speedway (Sanction No. 4046), 12.5 miles

Joe Verebley

30 June / Columbus, Powell Speedway (Sanction No. 3978), 7.5 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

4 July / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway (Sanction No. 3981), 20 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

4 July / Allentown, Allentown Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3980)

Cancelled

7 July / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway (Sanction No. 3982), 15 miles

Johnny Shackleford, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

7 July / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway, 50 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

14 July / Reading, Reading Fairgrounds, 15 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

20 July / Selinsgrove, Selinsgrove Speedway, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

20 July / DuBois, Gateway Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

21 July / Langhorne, Babcock’s Langhorne Speedway, 20 miles

George Robson, (Paul Weirick) Sparks/Weirick Offenhauser

21 July / Dayton, Dayton Speedway, 10 miles

George Connor, (Norm Olson) Olson

22 July / Selinsgrove, Selinsgrove Speedway, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

27 July / Harrington, Kent-Sussex County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

28 July / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway, 15 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

3 August / Washington, Washington County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

4 August / Columbus, Powell speedway, 7.5 miles

George Robson, (Paul Weirick) Sparks/Weirick Offenhauser

10 August / Bedford, Bedford County Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3992), 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

11 August / Batavia, Genesee County Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 3994), 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

11 August / Langhorne, Babcock’s Langhorne Speedway, 20 miles

George Robson, (Paul Weirick) Sparks/Weirick Offenhauser

11 August / Winchester, Funk’s Speedway, 10 miles

Elbert Booker, (Lawrence Jewell) Jewell Hal

18 August / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway, 15 miles

George Robson, (Paul Weirick) Sparks/Weirick Offenhauser

18 August / Skowhegan, Skowhegan Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

24 August / Hamburg, Erie County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

25 August / Hopwood, Uniontown Speedway, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

25 August / Dayton, Powell Speedway, 10 miles

George Robson, (Paul Weirick) Sparks/Weirick Offenhauser

30 August / Essex Junction, Champaign Valley Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

31 August / Flemington, Hunterdon County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

31 August / Altamont, Tri-County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

31 August / Hamburg, Erie County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

1 September / Flemington, Hunterdon County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

1 September / Winchester, Funk’s Speedway, 10 miles

Charles van Acker

1 September / Richmond, Strawberry Hill Raceway, Atlantic Rural Expositions Grounds

Cancelled

2 September / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway, 100 (97) miles

George Connor, (Ed Walsh) Walsh/Moore/Kurtis Offenhauser

2 September / Flemington, Hunterdon County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

2 September / Richmond, Virginia State Fairgrounds

Cancelled

6 September / Rutland, Vermont State Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Lee Wallard, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

7 September / Port Royal, Juniata County Fairgrounds, 8 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

8 September / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway, 15 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

15 September / Reading, Reading Fairgrounds, 12.5 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

15 September / Indianapolis, Indiana State Fairgrounds (Sanction No. 4014), 100 miles

Rex Mays, (Bowes Racing) Bowes/Stevens Bowes/Winfield

22 September / Milwaukee/ West Allis, Wisconsin State Fairgrounds, 100 miles

Rex Mays, (Bowes Racing) Bowes/Stevens Bowes/Winfield

22 September / Great Barrington, Great Barrington Horse Track, 4 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

22 September / Trenton, New Jersey State Fairgrounds

Cancelled

22 September / Dayton, Powell Speedway, 5 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

23 September / Allentown, Allentown Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

28 September / Bloomsburg, Columbia County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

28 September / Shelby, Cleveland County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Walt Ader, (Ted Horn Enterprises) Schrader Offenhauser

28 September / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway, 20 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

29 September / Trenton, New Jersey State Fairgrounds, 20 miles

Joie Chitwood, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

4 October / Frederick, Frederick Fairgrounds

Cancelled

5 October / Winston-Salem, Forsythe County Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Tommy Hinnershitz, (Ted Horn Enterprises)

5 October / Atlanta, Lakewood Speedway, 20 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

6 October / Goshen, Good Time Track, 100 miles

Tony Bettenhausen, (Bill Corley) Petillo Offenhauser

6 October / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway, 15 miles

Lucky Lux

6 October / Greensboro, Central Carolina Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

6 October / Dayton, Powell Speedway, 25 miles

Hal Robson, (Paul Weirick) Sparks/Weirick Offenhauser

12 October / Richmond, Strawberry Hill Raceway, Atlantic Rural Expositions Grounds, 10 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

12 October / Charlotte, Southern State Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

12 October / Spartanburg, Piedmont Interstate Fairgrounds

Cancelled

13 October / Greensboro, Central Carolina Fairgrounds, 7.5 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

19 October / Raleigh, North Carolina State Fairgrounds, 10 miles

Walt Ader, (Ted Horn Enterprises) Schrader Offenhauser

26 October / Charlotte, Southern State Fairgrounds, 15 miles

Hank Rogers, (Ted Nyquist) Peters Offenhauser

27 October / Mechanicsburg, Williams Grove Speedway, 25 miles

Bill Holland, (Ralph Malamud) Malamud Offenhauser

27 October / Greensboro, Central Carolina Fairgrounds Cancelled

9 November / Shelby, Cleveland County Fairgrounds, 15 miles

Ted Horn, (Ted Horn Enterprises) THE Offenhauser

10 November / Richmond, Strawberry Hill Raceway, Atlantic Rural Expositions Grounds, 12.5 miles

Tommy Hinnershitz, (Ted Horn Enterprises) Garnett Offenhauser

| Wins | |

| Ted Horn | 19 |

| Bill Holland | 18 |

| Joie Chitwood | 7 |

| George Robson | 6 |

| Walt Ader | 4 |

| Rex Mays | 3 |

| Bus Wilbert | 2 |

| Johnny Shackleford | 2 |

| Oscar Ridion | 2 |

| Elbert Booker | 2 |

| George Connor | 2 |

| Tommy Hinnershitz | 2 |

| Bumpy Bumpus | 1 |

| Joe Verebley | 1 |

| Charles van Acker | 1 |

| Lee Wallard | 1 |

| Tony Bettenhausen | 1 |

| Lucky Lux | 1 |

| Hal Robson | 1 |

| Hank Rogers | 1 |

Summary

Being a statistical record book despite the use of “historical” in its title, something that is definitely missing from the IICS 2012 Historical Record Book to make it anything remotely worthy of using the “historical” in the title is the lack any explanations for some of the more nebulous areas in the history of North American “Indy Car” racing. At the moment, the emphasis is far more on the “record” than the history, which is to be expected given that its purpose seems to be more a source for factoids and statistics than to provide any sense of the history of this form of racing.

I would suggest that Messrs Shunck and Sullivan seriously consider the issues that have been addressed in this review, otherwise each and every subsequent edition published of the IICS Historical Record Book in which the errors continue uncorrected will prompt a similar response until the history of “North American Indy car” racing is no longer the prisoner of the mythology that has distorted for far too long.

Not a threat, rather simply a promise to persevere until INDYCAR finally realizes that the history of “North American Indy car” racing prior to 1921 being peddle is, well, not quite the truth.

Notes

- Marshall Pruett, “INDYCAR: 20 Questions With Randy Bernard, Part 2,”, posted 27 December 2010 and accessed 5 May 2012.

- Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal, Volume X No. 5, 1 November 1905, p. 37.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Road Racing at Home and Abroad in 1908,” Motor Age, 7 January 1909, pp. 28-33. There are several additional pages, 34-41, covering reliability runs, hill climbs, other branches of motorsport, and support provided by the makers.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Road racing Performances of the Year,” Motor Age, Volume XVI No. 22, 25 November 1909, pp. 1-5.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- M. Worth Colwell, “1910 Season Produced Some Great Racing,” The Horseless Age, Volume 26 No. 26, pp. 910-913.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Motor Age’s Review of Road Racing,” Motor Age, Volume XX No. 24, 14 December 1911, pp. 1-8; “Many World’s Records Broken During 1911,” The Horseless Age, Volume 28 No. 26, 27 December 1911, pp. 976-980; “Résumé of the 1911 racing Season,” The Automobile, 7 December 1911, pp. 990-993.

- Fred Wagner, “Driver Herrick the Surprise of the Season,” New York Times, 12 November 1911.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Motor Age Review of 1912 Road racing,” Motor Age, Volume XXII No. 19, 7 November 1912, pp. 5-11.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Motor Age’s Review of 1913 Road Racing,” Motor Age, Volume XXIV No. 21, 20 November 1913, pp. 5-10.

- Jerome T. Shaw, “Complete review of 1913 Road Races,” The Horseless Age, Volume 32 No. 25, 17 December 1913, pp. 1025-1028.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Motor Age’s Review of 1914 Road racing,” Motor Age, Volume XXVI No. 24, 10 December 1914, pp. 5-10.

- Jerome T. Shaw, “1914 A Year of Records,” The Horseless Age, Volume 34 No. 24, 9 December 1914, pp. 839-840, 840a-840b.

- Ibid., p. 840a.

- Ibid.

- Harold T. Mason, “The Champions of Road Racing,” MoToR, December 1914, pp. 41-43, 136.

- Ibid., p. 43.

- Sinsabaugh, Motor Age, 10 December 1914, p. 9.

- Shaw, The Horseless Age, 9 December, pp. 840-840a.

- Jerome T. Shaw, “The Racing Champions of 1915,” The Horseless Age, 15 October 1915, pp. 354-358.

- Ibid., p. 355.

- C.G. Sinsabaugh, “Road Honors to Cooper & Stutz,” MoToR, November 1915, pp. 48-49, 102.

- J.C. Burton, “Earl Cooper Comes Back,” Motor Age, Volume XXVIII No. 17, 21 October 1915, pp. 5-9.

- J.C. Burton, “Anderson and Rickenbacher Speedway Champions,” Motor Age, Volume XXVIII No. 22, 25 November 1915, pp. 5-14.

- William K. Gibbs, “1916 Racing Review,” Motor Age, Volume XXX No. 23, 7 December 1916, pp. 5-13.

- “Championship Award for 1927,” Official Bulletin Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume II No. 20, 17 October 1927, p. 1.

- Actually, the ersatz national championships were created by Arthur Means and not Val Haresnape.

- Bob Russo, “Perspective: The 1920 Championship,” Indy Car Racing, January 1987, pp. 43-45.

- John Glenn Printz, “Perspective: A Second Look at the 1920 Championship,” Indy Car Racing, 15 January 1988, pp. 10-13, and 29 January 1988, pp. 12-14.

- H.A. Tarantous, “Another Year of Racing,” MoToR, January 1921, pp. 62-63, 208, 214, 218.