Rear View Mirror

Volume 7, No.6

Author

- Don Capps

Date

- March 29, 2010

Download

- RVM Vol 7, No 6 (PDF format, 508k)

“Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson | Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman

Automobile Racing History and History

or Case History and Casey and Clio Has a Corollary: Part II

|

The Jackets Corollary: It is practically impossible to kill a myth once it has become widespread and reprinted in other books all over the world1 |

| L.A. Jackets |

The Jackets Corollary is really a blinding flash of the obvious. Although it is derived from a case that related to military history, a discipline within history which suffers many of the problems that afflict automobile racing history, it seems to state one of the more serious problems with which historians must wrestle in automobile racing history. Once errors get disseminated into a variety of sources, primarily books, there is a tendency for these errors to take on a life of their own and continue to pop up years after they have been challenged and corrected.

Casey (and Case History) at the Battlements

The major basic – if not fundamental – difference between the card-carrying historians and the others involved in automobile racing history – the storytellers, the Enthusiasts, the journalists, the writers, as well as whomever else you might wish to name – comes down to this one thing: references.

Simply stated, it is the tools of the historian’s trade, footnotes, bibliographies, citing sources used, all of which allow others to follow the same trail as the historian, even if that results in different interpretations of the material, that separates the card-carrying historian from his brethren and sisters who may enjoy reading history – or what may appear to be history, but not the sausage-making aspects of the historian’s craft. Harsh, perhaps, but also a reflection of the reality that faces automobile racing history.

Although genealogists deal with history in the sense that they use documents of historical importance – census data, city books, pension rolls, muster rosters, and other data dealing with vital statistics – in their work, they are not historians. Indeed, they are often the bane of historians for a litany of reasons, not the least of which is the misuse of many documents as well as the destruction and theft of those documents in some – thankfully relatively rare – cases which denies their use to others. As well-intended as genealogists may be, as occasionally useful as they might be on rare occasions, they are, in general, simply genealogists and not historians.

So, too, is the case of automobile racing Enthusiasts when it comes to history. Just as sleeping in the garage will no more make you a car,2 neither will sleeping in the history section make you a historian. Indeed, even possessing a degree in history does not make one a historian – although it certainly helps, of course. This is not to say that an Enthusiast cannot also be a historian or vice versa, but there needs to be a distance, a coolness, an attempt at objectivity that a historian must assume which can be quite at odds with the way an Enthusiast approaches his or her sport, automobile racing in this case.

The history of automobile racing is so inconsequential that it almost cries out and begs for the attention of historians. That this history of automobile racing has been largely left in the hands of non-academic or non-card-carrying historians has led to the situation where what we know is less than what it would appear to be in most instances. That there are few writers who have transitioned to being historians – or at the very least “history-minded,” which is usually good enough given the usual lack of interest in the wiles of Clio – means that what is brought into view is usually the low-hanging fruit, the obvious.

It is often a surprise to discover how much that is of actual importance to historians as they attempt to decipher, interpret, and sort out the Zeitgeist or context of events, is often regarded as pit chatter or even gossip or simply referred to obliquely and then forgotten or ignored. A meeting to discuss such-and-such a matter, such as safety or starting money, might be referred to in a race report, but then there is no further reference to it. Nor does it appear in other places within that magazine or others. Yet, while the consequences of that meeting may directly influence the running of events, the safety of the racing machinery, the financial aspects of automobile racing itself, it is breezily dismissed as mere “politics,” the anathema of Enthusiasts.

The result is that far less of the story, the history, is told than should or could be. It creates gaps or lapses in the chronicle which are usually ignored, the race reports and technical analyses of the racing machinery being quite sufficient to satiate the Enthusiast. Driver and constructor articles tend to border on hagiography rather than studied consideration of the subject. That is unless the objective of the piece is a “hatchet” job, something not entirely unheard of within the world of automobile racing literature.

A good writer who is history-minded can often be more effective in presenting the history of some aspect of automobile racing than the historian who is not such a good writer, few card-carrying historians, academic or otherwise, being noted for the brilliance of their writing. This is, however, a discussion for another day.

Within the realm of Clio, the narrative form is pretty much in the academic doghouse in recent years, being relegated to the background as other ways to explore and interpret the past have come into – and out of – vogue. What follows are a few brief thoughts on the approaches to writing and recording automobile racing history.3 The empiricists still have a foothold with the profession, of course, since it is unlikely that any card-carrying historian would reject that approach as a means of conducting research. Looking into the past of automobile racing does tend to lend itself to the empirical model, of course.

I have often wondered as to the Marxist aspects of writing the history of automobile racing. There certainly exist elements within automotive history to which one could see how there could be interpretations that would lend to themselves to Marxist historical theories, but racing does seem to spring immediately to mind as one of those areas or elements. And, yet, if one does contemplate some of the various economic issues related to automobile racing, there are some possibilities where a clever Marxist historian could have a field day. For some reason, the British seem to provide the more obvious examples that spring to mind when history as interpreted through Marxism is considered.

When it comes to psychohistory, an area of historical inquiry for which we can thank Sigmund Freud, automobile racing would seem to be a rich vein to mine for material. One need only to read some of the autobiographies, biographies, and various interviews to see psychohistory – or at least some form of it – at work. Traditionally psychohistory concerns itself with psychoanalysis, but this particular discipline seems to have expanded and broadened its purview in recent years so as to examine psychological factors outside of psychoanalysis. This not an obvious form of history as it applies to automobile racing, but it might be more prevalent than one would assume at first glance.

While the Annales school would appear to have made its way into automotive history, it also seems to have drifted close to automobile racing history. The Annales school promoted what we usually refer to as the “interdisciplinary” approach, that is examining and considering factors other than political or diplomatic issues when the past is considered. This approach is useful when attempting to establish context and the existence of multiple variants, but there is a tendency for the quantification and the enumeration to often distract the historian and this presentation of data overwhelm any interpretations or observations that may be offered to the reader. If one has ever had to read the two volumes of the landmark work of the Annales school, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Phillip II,4 you would readily understand some of the strengths and limitations of the approach, especially with regard to using this as the sole lens through which to gaze upon the history of automobile racing.

I am wondering when it will become apparent that what is written about several topics in automobile racing history skirts over into the area of historical sociology. While sociology tends to not be thought of in any relation to history these days, about a century ago when the move to create chairs and then departments to consider issues of socialization, it was an outgrowth of the work of various historians who were examining the interactions of individuals and groups in a historical contexts. Historical sociology could lend itself to the examination of change and how different groups dealt with it and what were the factors that influenced one group and either did not affect another group or that there were additional factors and influences at work.

Within the field of automotive history are a number who are practitioners of quantitative history, which includes the approach known as Cliometrics. It might be a Blinding Flash of the Obvious to suggest that this is the discipline which firmly believes that “if it is not a number, it is not important.” Indeed, there are elements of automotive history, to include automobile racing, which readily lend themselves this type of an approach. It would be not much of a stretch to suggest that the interest expressed by many in the statistics and data associated with the history of automobile racing could be lumped into this field of inquiry.

Oral history has become one means for historians and chroniclers to record and pass along the words and observations of those discussing the past. In the realm of sports history, The Glory of Their Times,5 an oral history told in the words of baseball players who played in the early Twentieth Century, is probably the most successful and the best known. Lawrence S. “Larry” Ritter, a professor of economics at New York University, used a bulky, unwieldy reel-to-reel tape recorder to record the recollections of dozens of these players over a five year period, covering about 75,000 miles in his quest. Editing the conversations so as to provide them with a flow that one would expect if that same conversation took place around a table in a bar or the kitchen table in a home, the book became an mainstay of the sports history world, still in print and on the bookshelves of stores over four decades later.6

True, oral history is long-established form of history and one used with great success in the United States decades before the Ritter book, especially in the recording of the recollections of former slaves by the staff of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington. However, the Ritter book was the first successful use of this form in the sports history genre. Needless to say, Ritter spawned a number of imitators, Vrooom!: Conversations with the Grand Prix champions by Peter Manso being one of the more notable ones in the automobile racing world.7

While the oral history form is very good for providing a feel for the tenor of the times and often provides details that are often not obvious to even the most skilled historian, it must be approached with some caution. It is not just a case of memory being fallible, it is also that an oral history interview can only provide one person’s views of the past and, a factor often overlooked, it takes places after the events have happened are may be shaped by subsequent events or related factors, skewing the recollections of the person recording his or her memories. This is not to belittle oral history or suggest that the use of oral history should be avoided, only that oral history must be used with caution and is most effective when used in conjunction with other sources.

At this point, it would be another case of pointing to the obvious, but as can be seen the way in which history actually gets written or recorded is often done so with a blending and mixing of disciplines with the ways in which history, the past, is examined. Which, of course, brings us to the humble form which was mentioned at the beginning: the narrative.

For all of its dents and worn parts, the narrative is still an effective form of communicating history to the reader. It is not a surprise to find that most of the books on military history written in recent decades used the narrative form. As a staple of the history genre at bookstores, the appeal of military history is often that it provides the reader with a story, an ordered collection of events fashioned in some chronological sense and given to that reader so as to provide a beginning, an exposition or middle, and an end. It is a form as old as history itself.

The narrative, as simple a form as it may be, is not that easy a form when it comes to actually writing the narrative. One may have his or her facts in order, the order of events correct, the characters and events identified, and have all the moving parts in synch, yet the story be as interesting as watching latex paint dry. One of the problems of the narrative form is that it places almost as much emphasis on the ability to tell the story as to relate the history, hence the ability of the non-historians to dominate and, for lack of a better word, control the field of automobile racing history.

And, yet, it is the narrative which best lends itself to the incorporation of the other approaches to history that were discussed above. If automobile racing history is to become more “history-minded,” to become less focused on what the Enthusiast wants to read and more on what needs to be written, then it means that the narrative is the most likely form to accomplish this.

One of the longstanding problems with what has been written as automobile racing history, as mentioned several times and will continue to be mentioned it seems, is that it has tended to be written by Enthusiasts whose enthusiasm tends to blot out any sense of objectivity as well as numb any efforts at scholarship. This is a problem which seems to plague sports history and automotive sports history is no different in that respect.

Make no mistake, the Enthusiast is the backbone of sports, the mainstay of the arts, the bedrock of any pursuit that stirs the passions of mere mortals for the feats of others. It is their enthusiasm and love of a sport or other pursuit that infects others and creates the interest and excitement that we all experience in some form or another. With the rarest of exceptions, they simply do not make very good historians for the sport that they enthuse over. Their love, their passion, their enthusiasm tends to blind them to any notion of objectivity, unfortunately. Biography becomes hagiography and narrative becomes hymn and celebration is too often the result when the Enthusiast assumes the role of scribe.

It must be said, however, that love and enthusiasm should not be an anathema to the historian. Indeed, it is the love and passion for history itself, the scholarship, the discovery process, making sense of the flotsam and jetsam of the past, the connecting of the dots. Enthusiasts tend to look upon scholars in askance when this is mentioned.

An Enthusiast usually has little tolerance for an agnostic and often none for an atheist when it comes to their sport, their passion. That a historian may not be a “fan” of their sport and yet writing about its history is often beyond their comprehension. This was brought to mind by the decision of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) to grant credit to Dorothy Jane Zander Mills, the wife of the late Dr. Harold Seymour, for her work on what is known to baseball researchers and historians as simply “The Trilogy.” Seymour – and his wife – was the first to produce what is accepted as the first scholarly look at the history of baseball. Beginning with Baseball: The Early Years (Oxford) in 1960, Baseball: The Golden Age (Oxford) in 1971, and, finally, Baseball: The People’s Game (Oxford) in 1990, these three books are the beginning point for anyone attempting to write about or delve into the history of baseball.

What makes the contribution of Mills to the history of the game so interesting is this: “She cared nothing for baseball, only the scholarship...” In a telephone interview with The New York Times, Mills stated, “I am still not a fan of baseball. People can’t understand that. I think it’s a good idea to remain above that. You write a lot more objectively about a subject when you’re not in love with it.”8

Thus, we have the situation often arise when an Enthusiast is bewildered that a historian is quite cool and detached about the sport, not sharing the same fire and passion that the Enthusiast does. Instead, the historian questions many of the assumptions held about the past and often provides views very much at odds with what the Enthusiast is used to seeing and hearing about the sport and its past.

There is also a tendency for the Enthusiast to focus on information – that is to say, trivia – and not necessarily knowledge. This is a great part of the reason that box scores and related statistics and race data are such a part of what the Enthusiast tends to be interested in, not necessarily “low-hanging fruit,” but while certainly the sort of objective information that is necessary to develop understanding and knowledge, as those levels of affective learning that Bloom and others would describe as being higher on the scale than the acquisition of information and being able to arrange it in some fashion. That information often seems to be the source of trivia rather than as part of an effort to gain knowledge about a subject or topic.

It might be that the film critic Roger Ebert could have the last word on this – at least for the moment: “The fatal flaw in the concept of trivia is that it mistakes information for knowledge. There is no end to information. Some say the entire universe is made from it, when you get right down to the bottom, under the turtles. There is, alas, quite a shortage of knowledge.”9

Case History: The Curious Case of the 1933 Gran Premio di Tripoli

....or We Were Misinformed?

|

Captain Louis Renault:What in heaven's name brought you to Casablanca? Rick Blaine:My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters. Renault: The waters? What waters? We're in the desert. Blaine:I was misinformed.10 |

It is a source constant amazement as to just how one man, Alfred Neubauer, in one book, Manner, Frauen und Motoren or Speed Was My Life, could create two of the biggest myths in automobile racing history. In a chapter entitled “Melodrama and Tragedy” in the English language editions, Neubauer spins a yarn about the I Corsa dei Milioni, the VII Gran Premio di Tripoli, which took place on 7 May 1933.

Here is exactly what Neubauer (and his co-writer Harvey Rowe) wrote regarding the race:

It was in 1933 that the giant American airship Akron crashed in the Atlantic with all hands on board. Thirteen years of Prohibition ended in the United States. In Germany the cruiser Admiral Scheer was launched, Goebbels imposed a boycott on Jewish business-men and the first concentration camps were established. And in the Italian colony of Libya Marshal Italo Balbo opened the new racing circuit at Tripoli, the fastest in the world.

Unlike the narrow, twisting course at Monte Carlo, the Tripoli circuit was eight and a quarter miles long. You could keep up a speed of 120 m.p.h. – and break your neck.

The drivers were well aware of this. So too were the authorities. They wanted sensational publicity for Italy, for Mussolini's 'imperium romanum', and especially for Marshal Balbo, the new Governor of Libya, the elegant sportsman who had mapped out a brilliant future for himself.

A national lottery was organised. Months before the race, tickets were already on sale throughout Italy. For the ridiculous sum of eleven lire you stood a chance of becoming a millionaire. Three days before the race thirty lucky tickets were drawn, one for each of the starters. The winning ticket would win seven and a half million lire, about £80,000.

On the eve of the race a stout, bald-headed gentleman called at Achille Varzi's hotel and asked to see him. He was shown up. Varzi was resting on a couch in his private sitting-room, as immaculate as ever, his hair parted in the middle and smoothly brushed. He was wearing a light-blue smoking-jacket and a white silk scarf with a genuine pearl scarf-pin. With him that evening was a beautiful young woman whom I shall ca11 Sophia and who was to play an important part in Varzi's life.

The stranger introduced himself as Enrico Rivio, a timber-merchant from Pisa. He asked to speak to Varzi alone, and Sophia retired to the bedroom. Then Rivio explained why he had come: to ask Varzi to win the race next day.

It's not hard to imagine Varzi's reaction. He was surprised that Signor Rivio should have flown especially from Pisa to Tripoli just to make that request! But there was more to it than that. Rivio had drawn the lottery ticket with the number of Varzi's car. Varzi remarked, not without a certain bitterness, that the most he stood to win from what promised to be a dangerous race was a great deal less than Signor Rivio, the timber-merchant, would get out of it. And that was the point where Rivio put his cards on the table: if Varzi won, he could have half the prize-money. Moreover, he produced a document drawn up by his solicitor to that effect. Varzi thanked him, promised to do what he could and, as soon as Signor Rivio had left the room, telephoned Nuvolari. . . .

On May 7th, 1933, at Tripoli it was nearly 100 degrees in the shade. The hot desert wind, the Ghibli, was blowing across the plain. The new circuit ran like a white ribbon between the palm-groves and the yellow sand. The grandstand was ablaze with colour: Italian officers in their gaudy uniforms, colonial officials, Blackshirts, Arab sheikhs and women in all their tropical finery.

Nearby in a special box sat a very different group, thirty people from all walks of life, each with a scrap of paper that might be worth a fortune. There was a butcher from Milan, a pathetic old lady from Florence, a post-office sorter, a salesman and a student. A down-at-heel baron had somehow attached himself to a rich widow. And there too, of course, was Signor Enrico Rivio, the timber-merchant from Pisa, his bald head beaded with perspiration and pink with excitement.

As Marshal Balbo, resplendent in his uniform, his beard beautifully trimmed, raised the green, white and red flag, the thunder of thirty racing-cars echoed across the desert. And what followed must be unique in the long and varied history of international motor racing.

Three cars led the field from the start: first there was Nuvolari in his red Alfa, then Borzacchini close behind, followed by the ace Campari, who also possessed a sufficiently good tenor voice to sing at the Scala in Milan and had an uncle who was a famous liqueur manufacturer.

Others who got off to a good start were the Frenchman Chiron, Fagioli and Sir Henry Birkin in his green Maserati. The favourite, Achille Varzi, was somewhere in the middle of the field and seemed quite happy to stay there. Among the onlookers some suspected that he might be off form, others that he was simply biding his time. At the end of the fifth lap Campari was leading, with Nuvolari and Birkin second and third. Varzi's blue Bugatti was already fifty-seven seconds behind the leader. Signor Rivio was observed mopping

his brow.

In the twelfth lap Campari was nine seconds ahead of Nuvolari. Borzacchini had moved up, and Birkin was lying fourth. There was no sign of Varzi.

Two laps later Campari's engine began to splutter. He stopped at the pits and the mechanics dived under the bonnet like flies. A few moments later Campari eased his bulky figure out of the driving seat, his face purple with rage. But not long after he was seen in the canteen with a bottle of Chianti in front of him and his fury seemed to have passed.

On the twentieth lap Nuvolari was still in the lead, with Borzacchini on his tail and Chiron and Birkin not far behind. There were another ten laps to go, and Varzi now put on a spurt. By the twenty-fifth lap he had moved up to third place, and Chiron and Birkin had

dropped back. But suddenly the engine of Varzi's blue Bugatti began to make ominous noises. Two cylinders went dead. The car was slowing down.

One can well imagine Varzi's feelings. This was something he had not reckoned with. To stop for a change of plugs would mean losing three or four minutes-and the race. He decided to keep going. But what agonies Signor Rivio must have suffered!

At the end of the twenty-sixth lap the crowd were shouting Nuvolari's name, and the flying devil from Mantua looked like lapping Varzi. Then on the twenty-seventh lap Borzacchini was seen to be looking back anxiously, as if he was afraid Varzi might pass him.

And yet Borzacchini was not driving full out, and Varzi's car was obviously limping along.

What happened next was still more extraordinary. Borzacchini cut one of the curves so close that his front wheel hit one of the empty oil-drums at the edge of the track. The drum sailed through the air, the car skidded and Borzacchini, without any difficulty, brought it to a standstill. A few moments later he trundled into the pits with one tyre blown. But he seemed singularly unconcerned at having to retire. Nuvolari entered on the last lap thirty seconds ahead of Varzi.

With a mile and a half to go the crowd noticed that Nuvolari was also throwing anxious glances over his shoulder. They cheered him on wildly. When his red Alta appeared at the beginning of the home straight they went mad with excitement. But the shouting quickly died away when they saw the red Alfa slow down and stop only a few hundred yards from the finish. Nuvolari climbed out of the car and stood in the middle of the track, wringing his hands: 'No petrol,' he howled. 'No petrol.'

Mechanics rushed out of the pits with petrol-cans and emptied them into the tank. While they were doing so two cars came in sight round the bend, Varzi's and Chiron's. Both were crawling. And the bewilderment and suspense were indescribable as Nuvolari

joined in this fantastic slow-motion finish. Varzi won literally by a tyre's breadth from Nuvolari, with Birkin third. In the general excitement it had been forgotten that Chiron was one whole lap behind.

Varzi, bathed in perspiration and completely exhausted, was lifted out of his car and carried shoulder-high to receive his prize. Among the first to congratulate him on his victory was a stout, bald-headed gentleman whom nobody knew – Signor Rivio.

That evening, as Varzi, Nuvolari and Borzacchini sat in their hotel drinking the most expensive champagne, the rumours began to gain ground. Where they originated no one will ever know, but in a remarkably short time there was talk of a rigged lottery and a racing scandal in the newspaper offices and the racing headquarters.

The following morning the supreme sport authority in Tripoli met in special session. The President opened the proceedings with a direct charge that certain drivers had agreed before the race that Varzi should win. One of his colleagues asked who the 'certain

drivers' were. The President named Varzi, Nuvolari and Borzacchini as the main culprits, with Campari and Chiron as strong suspects, and he demanded that all these drivers should be immediately disqualified and have their licences withdrawn.

There was a long, uneasy silence. To disqualify these five drivers, the finest in Europe, really meant disqualifying international motor racing. The proposal was not even put to the vote. The drivers in question were merely given a warning. But from then on new and

stricter regulations were introduced. The thirty lottery tickets were to be drawn in future five minutes before the start of the race when the drivers were already in their cars.

Twenty-five years later Canestrini, who by settling the feud between Varzi and Nuvolari had unwittingly prepared the ground for this coup, found that it was perfectly legal and helped to stimulate motor-racing! My own view is that, technicalities aside, any chance

to increase the earnings from such a dangerous profession is worth taking. Good luck to them! 11

As with Rick Blaine, however, we seem to be misinformed.

With surprisingly little variation, this story has been making the rounds in automobile magazines – and even books – for over four decades. The list includes such as magazines as Automobile Quarterly, Autosport, Car and Driver, Ford Times, Motor Sport, Road & Track, Sports Car Graphic, Vintage Racecar Journal, as well as the book Power and Glory; there are others, of course, but this is a representative sampling of where the articles appeared. The articles were written by such noted authors as William Court, Charles Fox, Richard Garrett, Mark Hughes, Robert Newman, Chris Nixon, Charles Proche, Joe Saward, Rob Walker, and Eoin Young, to name, as they, but a few. It should be noted that the authors are all writing in English.

The problem is simple: how do you weigh the version provided by Neubauer against this contemporary account from Motor Sport?

The Grand Prix of Tripoli, organised for the first time since 1930, was this year marked by a titanic struggle between Varzi (Bugatti) and Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo). The two had met at Monaco when Varzi just won, and the race at Tripoli was in the nature of a 'return'.

Additional interest was given to the race this year by a sweepstake, organised on the lines of the Irish sweepstake with the exception that there was only one 'unit'. Altogether, a sum of 15 million lire was subscribed, the first prize being over three million, (second one) million and the third being over 800,000 lira.

Judging by the colossal crowd which lined the course at the start, the future of the Grand Prix of Tripoli is assured. The scene at the start was a most impressive one, and a few minutes after three o'clock Marshall Badoglio, Governor of Tripoli, gave the signal to start. The cars were lined up in rows of four, and an initial lead was gained by Gazzabini (Alfa Romeo). His lead was short-lived, however, for a group of faster cars soon enveloped him, and to the joy of the few Englishmen present, it was seen that Sir Henry Birkin had forged his way to the head of the bunch of bright red cars.

Although the Mellaha circuit measures 13 kilometres, it is tremendously fast, and in a very short time the cars appeared once more at the end of their first lap. Birkin, handling his new Maserati –with consummate skill, was in the lead, followed by a howling pack composed of Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo), Campari (Maserati), Varzi Bugatti), Fagioli (Maserati), Borzacchini (Alfa Romeo), Biondetti (BM) Zehender (Maserati), Premoli (B.M.), Hartmann (Bugatti), Castelbarco (Alfa Romeo) and a straggling group of slower machines.

Birkin continued to give a masterly display of driving, and held his lead for four laps. Then the veteran Campari put his foot down well and truly, passed the astonished Nuvolari, and on the fifth lap took the lead from the Englishman. As the cars came past the pits Campari (Maserati) led, having covered 65.5 kilometres in 22 min. 58 sec.; Birkin (Maserati) was second, 9 sec. behind; Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) was 5 sec. later than Birkin, and he was followed by Varzi (Bugatti), Zehender (Maserati) and Fagioli (Maserati).

Some idea of the speed at which the race was being run can be gauged by the fact that Campari, who led at the end of 10 laps, had covered the 131 kilometres at an average of roughly 107 m.p.h. Nuvolari had by this time got ahead of Birkin, but the English driver was courageously sticking to his guns and was only a few yards behind.

On the 14th lap Campari pulled into the pits in order to refuel, he was joined by Fagioli. This stop gave Nuvolari the lead, half-distance the order was:

Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo), 1h 9m

Birkin (Maserati), 1h 9m 10s

Varzi (Bugatti), 1h 9m 19s

Campari (Maserati), 2 minutes later.

Zehender (Maserati), 2 minutes later.

Sir Henry Birkin's chances of victory were spoiled by his having to refuel on the 16th lap, and although this operation was carried out the usual rapid manner, both Campari and Zehender had slipped by when he got going again. Then Campari had to stop again to replenish his oil tank which had come loose in its seating. After 15 minutes delay while much rope was used to lash the tank securely, Campari started once more, but after a few laps he retired.

At 20 laps Nuvolari still led, but Varzi was now right on his tail. The Bugatti driver was giving a model display of cool driving, appearing obvious of the existence of other competitors, and concentrating on his polished handling of his own car.

On the 25th lap a shout went up when it was seen that Varzi had gained the lead. Nuvolari had evidently had a setback, for he was 20 seconds behind. On the next lap he drove like a demon and caught up the Bugatti. Nearer and nearer drew the red Alfa Romeo, each lap cutting down the French car's lead by a few feet. The crowd were wild with excitement, and a terrific roar was heard when, at the end of the 29th lap, Nuvolari came by the stands in the lead. As they disappeared on the last lap the spectators could hardly contain themselves, and craned their necks to see the cars come into sight for the finish. From a distance the two cars looked level, and they roared towards the finishing line almost abreast. But the blue car was slightly ahead and to the sound of a tremendous cheer Varzi crossed the line barely a length ahead of his rival.

Henry Birkin gave a magnificent performance in finishing third and, but for his pit stop, would have been nearer the leaders then his time indicated. Zehender had the misfortune to retire on his last lap.

Results

1st : Varzi (Bugatti) 2h 19m 51 1/10 s -168.598 k.p.t

2nd: Nuvolari (Alfa Romeo) 2h 19m 51 2/10 s

3rd: Sir H. Birkin (Maserati) 2h 21m 23s

4th Battilana (unspecified) 2h 21m 57s

5th Taruffi (Alfa Romeo).

6th Balestrero (Alfa Romeo).

7th Ghersi (Bugatti).

8th Battaglia (unspecified) 4 laps

9th Hartmann (Bugatti) 4 laps

10th Castelbarco (Alfa Romeo) 4 laps

11th Matrullo (Maserati) 5 laps

12th Cucinotta (Talbot) 5 laps

13th Barbieri (Maserati) 6 laps

The first three cars all used Dunlop tyres.

There is also this contemporary account of the race:

There is no doubt that Nuvolari's failure to win this race did not diminish his fame in any way. In fact, one could say that Nuvolari was morally the victor as he was in the lead from the fifteenth lap, setting a cracking pace, until he had to stop at his pit for almost a minute; when he re-started he was nearly a minute behind Varzi who had meanwhile assumed the lead. This disadvantage was soon totally quashed by Nuvolari and, in an unforgettable pursuit which lasted for seven laps, the Mantuan reached the finishing line only one fifth of a second behind the winner.12

Here is yet another contemporary account of the race at Tripoli:

Nuvolari was duly beaten in this race by Varzi but many people, without knowing the reason, did not really believe in this defeat. On the one hand, it is ridiculous to think that the two drivers had agreed a "fiddle" yet, on the other it is true that the two drivers (and Borzacchini, who retired) had made a pact with three holders of their [lottery] tickets. It would have not mattered who had finished first. Nuvolari stopped to refuel on the 23rd lap and Varzi assumed the lead; from then on, he was vehemently pursued by Nuvolari. At the beginning of the last lap Nuvolari was hard on Varzi's heels; the two appeared on the finishing straight almost at the same time, first Nuvolari, then Varzi… only a few hundred meters to go and Varzi accelerated irresistibly to get ahead of Nuvolari by half a length! Wild and lengthy applause from the excited crowd greeted both the victor and the vanquished.13

Comparing these race reports quickly points out some obvious variances with the tale as related by Neubauer. The finish of the race described in all three reports in bears no relation to the cars crawling to the finish line, Nuvolari meekly following Varzi home after a last lap stop for fuel, a key element in the legend. It is only in the report found in L'Auto Italiana that we begin to sense that something may have indeed been up, but what exactly? What happened in Tripoli?

The real story starts with the Italian colony of Libya – or Tripolitania – in North Africa. The colony is looking for sources of income to offset the balance of payments from Rome. Likewise, the Fascist government is also looking for ways to promote the colony. Rome is looking for ways to entice people to visit and then – hopefully – settle in Libya. Tourists are not being attracted in numbers as large as desired, much less immigrants. So far, the results have not been encouraging.

With motor racing a popular sport among the Italians, seemingly regardless of where they were located, in 1926 a racing circuit is constructed on the outskirts of Tripoli, the capital of the colony. From 1925 until 1930, races are held which, despite some early moderate success, quickly become financial flops. The 1929 race is held only due to direct intervention of the governor, Emilio de Bono. Governor de Bono managed to persuade sponsors to back the event and the race went ahead. However, the last race held in Tripoli, 1930, was a financial disaster with the deadly combination of a small field – only 12 cars on the grid, racing over a long 26.2 kilometer circuit, a small crowd, and the death of a very popular driver – Gastone Brilli Peri, the previous year's winner – resulting in the organizers being unable to hold a race the following two years.

Undaunted by all this, in 1932 the president of the local auto club in Tripoli, Egidio Sforzini, organizes another attempt at hosting a race in the Tripoli. This time it is to be an "European" type circuit, one built for the sole purpose of racing much like Montlhery, AVUS, or the even the Nurburgring. The circuit will be built outside Tripoli in the suburb of Mellaha. However, funding is tight and what there is available is due only to the Fascist government pouring money into a fair promoting tourism and settlement of the colony. The money for the new circuit is allocated only as a side attraction to entertain the expected tourists.

Meanwhile, there is an Italian journalist who is musing upon both the new Mellaha circuit and the very popular Irish Sweepstakes. Using the Irish Sweepstakes as the starting point, the journalist thinks that rather than creating a lottery based upon selling chances to be selected as the lucky holder of the ticket for the winning horse and thus win the jackpot, Giovanni Canestrini thinks the same scheme can be applied to a motor race. Canestrini is the editor of La Gazzetta dello Sport, one of the most popular sporting papers in Italy. His opinions and ideas carry considerable weight in the Italian sporting world. Egidio Sforzini, is approached by Canestrini with the scheme for a sweepstakes – a lottery – in conjunction with a race being scheduled for the Spring of 1933.

The lottery will supply the much needed money for the new circuit, fill the coffers of the Automobile Club di Tripoli, as well as provide both enormous publicity for Libya and large crowds for the race. Canestrini is offering Sforzini an idea that is simply too good to resist. It must be kept in mind that the Mille Miglia was another scheme that Canestrini masterminded and successfully brought to fruition. Sforzini envisions a truly modern racing circuit, one that will use lights for the start, a photo-electric timing system, and generous facilities for both the participants and the spectators. This took money, more than being allocated by the government in Rome.

Sforzini is enthusiastic over the idea as laid out by Canestrini and readily agrees to the plan.

Canestrini then takes the idea to Governor Emilio de Bono, who is an old acquaintance from prior to The Great War. Bono, soon to be the Colonial Minister in the government, is willing to entertain any notions that might help develop the prospects of Libya. De Bono is also enthusiastic over the scheme and lends his support to the Automobile Club's – Canestrini's – plan. This now sets the wheels into motion to bring the idea to fruition. The appropriate agencies pass the idea onward and upward until where it finally reaches Mussolini. Mussolini reviews the sweepstakes scheme and personally approves it.

On 13 August 1932, aboard the Royal Yacht ('Nave Reale') Savoia, Royal Decree 1147 is signed by King Vittorio Emanuele III authorizing the lottery. The lottery tickets will be sold for 12 lire and the proceeds will be used to fund promotion of Libya as bankroll the race. When de Bono departs to accept his new position in the Fascist Government, the new governor, Pietro Badoglio, is briefed on the scheme and lends his endorsement to the lottery as well.

The Lotteri dei Milioni and the Corsa dei Milioni are now off and running. The first lottery tickets go on sell during October 1932. The last date for selling the tickets is set for 16 April 1933. It is still somewhat unclear as to exactly how much the lottery actually raised. Whatever the amount was, it was a huge amount of money for the time in Italy, especially with the effects of the Great Depression now being felt, even in Italy. To the best of our knowledge, the lottery "cleared" (to use Canestrini's term) at least 15,000,000 lire. That is an astounding number of 12 lire lottery tickets.

According to Canestrini, the breakout of the money was allocated this way: 1,200,000 lire to the AC di Tripoli for its expenses; 550,000 lire for starting and prize money; and, 6,000,000 lire to the winners holding the tickets of the top three finishers - win, place, show - in the race. First place was worth 3,000,000 lire, second place 2,000,000 lire, and third place 1,000,000 lire. These are not small numbers in 1933. As the Poet once wrote, "Gold drives a man to dream…."

And, the prize money for the race – at least a sizable chunk of the 550,000 lire mentioned by Canestrini –was very, very generous. In most cases, the prize money for a race during this time was relatively small, usually being paid only for the top several positions, with the "real" money paid out by the organizers being in the form of starting or appearance money. In this case, the prize money was enough to guarantee that there was some very serious money to be made by finishing well in the Corsa dei Milioni. Needless to say, nearly all the top teams, especially all the major Italian ones, were there.

When you add up the numbers given by Canestrini, it comes out to 7,750,000 lire. This is slightly over half of what was claimed to be collected by the sale of the tickets. What happened to it? While Canestrini or anyone else does not mention it specifically, the remainder was apparently both the money used to promote the Libyan colony and "overhead." This latter category might be a polite way of saying that given the tenor of the times, some of it went into the pockets of some of the big shots in the Fascist government.

The counter-foils of the lottery tickets were sent to Tripoli for the drawing several days after the last ticket was sold. The drawing itself was held on Saturday, 29 April 1933, eight days prior to the race. The drawing was supervised by the governor, Pietro Badoglio. Each of the 30 entrants in the race – including Giuseppe Bianchi who was to apparently withdraw after the drawing took place – had a ticket drawn and assigned to that entry for the race. After the assignment of the tickets to their entries, the ticket holder was notified by a telegram from the organizers. There is sufficient time to ponder the wealth that awaited the winner of the lottery. There is also plenty of time to seriously consider various means to narrow the odds.

The drawing was, as mentioned, held on a Saturday which happened to be the day prior to the running of the Gran Premio di Alessandria. The attention centered on the Tripoli race a week later was blamed for the relatively poor entry by the organizers of the Alessandria race. Plus, there was the fact that Varzi was not allowed to participate in the race! Although he arrived at the circuit and was allowed to practice, his entry had arrived too late and he was, therefore, denied a spot on the grid. Needless to say, this did nothing to improve his disposition since not starting the event literally denied him his starting money. On Sunday, Nuvolari won the event from Carlo Trossi and Antonio Brivio.

Now we get to the interesting part. In an account recorded by Aldo Santini in his biography of Nuvolari, Santini uses notes taken from his interviews with Varzi to reconstruct the events surrounding the Tripoli race. Since Varzi had nothing to gain from being untruthful, there is a strong tendency to take him very much at his word. In addition, we also have what Canestrini says along with additional information from Nuvolari biographer Johnny Lurani.

At some point on the same day of the drawing, Nuvolari apparently contacted Canestrini about a meeting as both were in Alessandria for the race. Canestrini and Nuvolari met, but also present were Varzi and Borzacchini. Later, Canestrini would claim that the topic of the meeting was solely the discussion of travel plans to the Tripoli race the following weekend. Varzi, however, said that the only topic discussed was the race the next weekend in Tripoli and the lottery. Although Santini states that also present were the ticket holders of the of the Nuvolari, Varzi, and Borzacchini entries in the race, given the circumstances, this is not thought to be the case.

Obviously there is some confusion here. It is possible that Canestrini was being evasive. Canestrini was not universally revered. His habit of writing a race report while sitting in his comfortable office at the newspaper when he was supposedly at the event was known to many of the other journalists and eventually to his readers. Canestrini stated that he was unaware of the "true" meaning of Nuvolari pointing his finger at him while on the grid at Alessandria telling him to remember the meeting the next day in Rome. He states that his assumption was that the meeting was to discuss the travel plans for the following weekend. He then goes on to say that Varzi set him straight. Canestrini states that Varzi informed him that the meeting as to discuss the lottery, not the travel plans for the race.

The three drivers – Nuvolari, Varzi, and Borzacchini, the three ticket holders, and Canestrini did indeed meet, but the meeting was in Rome early in the week following the drawing, on Monday evening. The site was the Massimo D'Azeglio – near the Termini station, one of several hotels owned by fellow racing driver Ettore Bettoja, who also served as the host for the meeting. Canestrini states that he was asked to be present for the meeting to ensure that there was a neutral party who could arrange the terms so as to avoid any conflict with the regulations. In some accounts, Bettoja is named as the lawyer or notary who brokered the agreement. While Bettoja was indeed present, he was acting only as the host and simply provided the room for the meeting.

Johnny Lurani supports that Canestrini was indeed the mediator who negotiated the agreement between the holders of the tickets. What is rather murky is how the three ticket holders got together. It is entirely possible that Nuvolari may have spoken to Canestrini in Alessandria to make the arrangements. Canestrini is quiet on any such notions.

Valerio Moretti gives the name of the holder of the lottery ticket for Nuvolari as Alberto Donati, of Cellino Attanasio, Teramo. The man who drew the ticket for Varzi is usually given as Enrico Rivio from Pisa – largely on the strength of the Neubauer account of the race. However, Moretti gives his name as Arduino Sampoli from Castelnuovo Beradegna, Siena. The holder of Borzacchini's ticket is given as Alessandro Rosina from Piacenza. It with these three men and the three drivers that Canestrini negotiated the agreement.

Again, as Varzi recounts, the meeting was held to discuss the very specific topic of how, "to find a formula which did not contravene the sporting rules," specifically how to divide the lottery money among what became known as The Six. This was scarcely a secret meeting. The 15 May 1933 issue of Moteri, Aero, Cicli e Sport reported not only that the meeting had taken place, but that someone had approached Piero Ghersi with an offer of 1,000,000 lire if he won the race. Others have Henry “Tim” Birkin being offered either 70,000 or 100,000 lira by his ticket holder if he won the race.

According to Moretti, The Six – as some were to call them – formed a syndicate which pooled the prize money from the lottery and which would be split equally among them, as long as one of the three drivers won the race. The idea is generally credited to Donati. The drivers would receive half of the winnings of the syndicate, again to be split equally among those involved. And they also, something to remember, got to keep any of the prize money they won as well.

Once the parties agreed to the arrangement they had discussed, it was also agreed that it should be put in writing. Apparently Canestrini wrote up the agreement and had it signed by all the participants. Once more according to Canestrini, once the agreement was signed by The Six, a notary reviewed and then notarized the document. In any case, the manager of the local branch of the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro was summoned and given the document to either notarize – according to some accounts – or to hold until the appropriate moment. The agreement was then deposited in the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro for safekeeping.

The important outcome of the meeting was that there was to be no pre-arrangement in the document as to the outcome of the race. Canestrini and Lurani both make a deliberate point of stating this. There was no flipping of a coin or any discussion about who should win. What was decided was that regardless of whether Nuvolari, Varzi or Borzacchini won the race, the jackpot was to be split evenly among The Six. As long as one of the three drivers won the race, each member of the syndicate would receive approximately 500,000 lire – regardless of who finished first. Add another 333,000 lire if one of the three drivers also finished in second. With an additional 166,000 lire or so should they swept the top three positions, each member of the syndicate would win tidy 1,000,000 lire. This was a good haul for one race in 1933. Even just taking the top two positions would reap a significant windfall for all involved: approximately 833,000 lire for each person, plus for the drivers any prize monies they earned.

Even before the meeting, the sporting papers were printing reports – which, interestingly, are nearly identical in content – about the purpose and probable outcome of the meeting. That is, all except one: La Gazzetta dello Sport. And the absence of such reports was remarkable, since its motor sports editor was none other than – guess who? – Giovanni Canestrini! Indeed, La Gazzetta is alone among the sporting journals of the day in being strangely quiet about the entire affair.

Canestrini was similarly quiet about any remuneration that he may have received as a result of his role in this affair. While it is never clearly stated, apparently Canestrini did not do this solely out of his love for the sport. Moretti quotes Lurani as mentioning that one – or perhaps all of the trustees – presenting a Fiat Balilla to Canestrini as a token of their gratitude.

Interestingly enough, the whole thing was quite legal, even if somewhat questionable in terms of judgment. One point made very clear later on was that Nuvolari's entrant, Enzo Ferrari of Scuderia Ferrari, was not a party to the proceedings. Indeed, on 15 May, Ferrari – according to Moretti – had Nuvolari issue a statement making it clear that "…the Scuderia Ferrari was extraneous to the agreement with the ticket-holder paired with his name." Whether Ferrari was upset with the financial arrangements being made without his involvement or on moral grounds is somewhat unclear, but one senses it was the former.

So finally, The Six arrive in Tripoli for the race. Many of the other drivers in the race were quite unhappy about the "arrangement" and they were quite vocal about it. Campari and Fagioli were said to be especially hostile to both Varzi and Nuvolari. Both made it clear that they were determined to win the race and ruin it for the "conspirators" and the "coalition." Birkin may also among those whose speed may not have entirely due to simply trying harder, pour le sport. Canestrini mentions Birkin as being among those who wanted to win the race to upset the apple cart.

It is interesting to note that Lurani points out that both Campari and Gazzabini were turned down in attempts to make similar deals with their ticket holders. Campari and Birkin then entered into a personal agreement to foil the efforts of the "conspirators." Gazzabini was also very unpleasant towards Varzi and Nuvolari, heaping scorn on them and making threats.

According to Canestrini, Varzi responded by saying, "Do whatever you like, I will drive my own race." Nuvolari in particular seemed to be impressed by the vehemence directed at Varzi, Borzacchini and himself. In an effort to calm matters down, Nuvolari promised the other drivers to play "50/50." Canestrini goes on to record with the answer Nuvolari gave when asked by Varzi as to how he could make such a promise, "It is quite simple: since you can't make 50/50 with everyone it is evident that I will share with nobody."

Lurani does not mention the coin toss to decide the winner. However, as usual, it is Canestrini who supplies the story. Varzi was said to be quite aware that Campari and several others were counting on the often heated rivalry between himself and Nuvolari to result in the both of them taking each other out of the race. According to Canestrini, Varzi approached him on the morning of the race about his concerns that Nuvolari might forget about the money and re-heat the always smoldering feud and cause them to lose all that money.

In the Canestrini version of things, Varzi and Canestrini then went to see Nuvolari and this concern was laid out and discussed. Nuvolari said he understood and proposed that Canestrini toss a coin and that the winner would be the one to cross the line first. The agreement with the ticket holders – and the money – was far more important than the victory itself. Varzi agreed to the solution. Canestrini tossed the coin and Varzi won. Nuvolari then agreed to honor the arrangement. Borzacchini apparently was never consulted about the coin toss or any finishing instructions as far as we know.

Keep in mind, however, that this is the Canestrini version of things, there not being any collaborating evidence to verify the coin toss even being done, much less it being done to determine the finishing order. Which, on the whole was quite presumptuous to begin with since there were no guarantees as to the final order including either Varzi or Nuvolari.

The twenty-nine – not thirty as often noted – entries lined up on the grid in the order determined by the drawing of ballots, which also determined the race numbers. For some reason, Borzacchini and Cazzangia lined up out of numerical sequence. Once the grid was formed, Governor Badoglio pressed the button to activate the starting lights.

When the starting lights came on, Carlo Cazzangia took off like a rocket in his Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 grabbing the immediate lead. However, as the field came around to complete its first lap, Birkin was leading the race. Birkin was followed by Nuvolari, Giuseppe Campari (works Maserati 8C-3000), Goffredo Zehender (Raymond Sommer-entered Maserati 8CM) who started from the fifth row, pole-sitter Premoli, and the rest of the pack. When the field came round the next time, it was led by Campari who had passed both Nuvolari and Birkin and was starting to already draw out a small cushion. On this lap Luigi Fagioli peeled off and pitted his Maserati 8CM for a plug change. Varzi was nursing his Bugatti along on seven cylinders due to the mechanics topping off the engine with oil at the last minute and while doing so overfilling the sump, a not uncommon problem with the Bugatti. The experienced Varzi realized that once the oil level was reduced, it would start running on all eight cylinders.

Just short of the halfway point, after 14 laps, Campari pitted. His oil tank was coming adrift and causing problems with lubricating the engine. After several quick, frantic attempts to bolt it in place, the offending tank was finally secured in place with rope found in the pits. However, after several more laps Campari was forced back into the pits to deal once more with the offending part. Yet another attempt to make further repairs was halted once it became apparent that the lack of oil had produced a death rattle in the engine of the Maserati. Campari did not give up easily. His efforts to win would seem stirred by his anger towards Varzi and Nuvolari.

On the same lap that Campari originally pitted, so did Birkin. Birkin pitted his Maserati to refuel. The stop was utterly routine, the only drama being Birkin accidentally getting a burn on his arm from the exhaust pipe, an all too common occurrence and an occupational hazard in those days. As noted, it was done quickly and with a minimal fuss. Neither Canestrini nor the report in Motor Sport mention anything out of the ordinary about his pit stop.

When Campari pitted, Nuvolari swept into the lead. Varzi and Zehender were now in second and third places, with Birkin now in fourth and going very well, showing no apparent ill effects from the burn suffered during his pit stop. After 23 laps, Nuvolari roared into the pits for the modern equivalent of a "splash-and-go." The pit stop itself took only 20 seconds, quite a remarkable time when it is realized that most pit stops of the day were measured in minutes. However, it cost him a total of about a minute entering, stopping, and then leaving the pits. The Varzi Bugatti, as it turned out, was fitted with an additional fuel tank with Varzi planning to avoid a pit stop and run the race non-stop.

Nuvolari screamed out of the pits roaring after Varzi. Over the last several laps of the race, Nuvolari carved big chunks of time off the lead that Varzi had built up. Some of the time was gained when Varzi experienced difficulties switching to the spare tank. Canestrini wrote that he stationed himself on the Tagiura Curve not only to keep an eye on Varzi and Nuvolari, but also signal to them to remember the agreement. As Varzi struggled with his fuel tank switch, Nuvolari finally managed to not only catch Varzi, but actually pass him. Nuvolari, under the clear impression that the deal was off since Varzi was apparently in trouble – assuming that there actually was such a deal, of course, had the bit in his teeth and going for it. Canestrini mentions that the drivers were shouting and making gestures at each other, but neither one was slowing down and neither were they paying any attention to his futile efforts to get them to slow down. They entered the last lap almost dead even and stayed that way well into the lap.

On the last part of the last lap Nuvolari was almost literally side-by-side with Varzi. Going into the last turn before the finishing straight, however, the advantage lay with Varzi. His Bugatti could still both out-brake and out-accelerate the Nuvolari Alfa Romeo. And Varzi was using all the road making his Bugatti as wide as he could make it. Despite the frantic efforts of Nuvolari to pass him before last turn, Varzi braked later into the corner and then tucked in behind, at the last second rushed away from Nuvolari, using the slipstream to assist him over the last few hundred meters. At the finish line Varzi was a scant 0.2 seconds ahead of the Flying Mantuan after Nuvolari's heroic effort to catch the Bugatti simply fell short. Had there been a 31st lap, the finish could have easily been reversed.

In his book, Moretti has Nuvolari – in a "crisis of conscience" – lifting his foot and allowing Varzi to pass for the win. It seems difficult to accept this judgment. As even Canestrini points out, Varzi and Nuvolari were racing and ignoring any outside influences to moderate their speed and keep in mind the "deal" that had been made. The two drivers had engaged in a series of close battles on the track over the past several seasons and while they were apparently civil to each off the track, they went at it hammer and tongs while on the track. Keep in mind that it did not matter financially who won, only that one or the other did indeed win the event. While Varzi may have won, it was not a gift from Nuvolari.

Birkin was to die on 22 June 1933, from what most initially thought was as the result from the burn he received. Apparently the Englishman neglected to have the burn attended to or it was later to become infected for another reason. In June, Birkin was hospitalized with his health in serious danger. Although most accounts attribute his subsequent death solely to his burn turning septic, there is reason to believe that while it played the major role, something else was a contributing cause. During the Great War, Birkin served in the Middle East and fell ill – as did many others – with malaria. It is now thought that Birkin suffered an untimely relapse of the disease and in a weakened condition from the apparently untreated burn, died. Had he not suffered the burn, or had it been properly attended to, it is thought that he could have survived the relapse and returned to racing. It must be noted that while the burn may have played a role, Birkin may have been in danger regardless.

While there was much grumbling and grousing by the other drivers and ticket-holders, "The Six" and Canestrini had acted within the rules as well as the law. Even Lurani makes that point very clear. All those within the syndicate made a tidy profit from the affair and got on with life. Within a few months the storm and the dark clouds that hung over the actions of the syndicate dissipated. One factor was the death of both Borzacchini – whose joy at the financial windfall was "a pleasure to witness" according to Lurani – and Campari at Monza that Fall. Another factor was that the Fascist government silenced criticism of the plan and quietly took steps to ensure that there would not be a repeat of 1933.

When the next Corsa dei Milioni was run in 1934, Marshal Italo Balbo was now the Governor of Libya. And he did make one small change in the procures as to when the tickets from the lottery were drawn: 30 minutes prior to the start when the cars were already on the grid and the race was about to start.

Sforzini suffered at the hands of the many critics as to what had happened. In 1936, he was replaced as President of the Automobile Club del Tripoli by Ottorino Giannantonio. Sforzini was then forced to return to Italy and allowed to fade into obscurity. He was forgotten by those within the racing community with one exception: Canestrini. After his death in February 1956, Canestrini – still editor at La Gazzetta dello Sport all those years later – published an obituary for his friend Sforzini.

This is scarcely the sordid tale that Neubauer spun and the many others then parroted. Indeed, it is a much more complex and nuanced story, a far more complicated tale than the one created by Neubauer, to say nothing of being much more ambiguous. It is a far more interesting and fascinating story and casts new light on the principal players involved in the arrangement. It also opens many new doors to explore….

Let me give credit where credit is due, especially since this is also a part of the story. The first voice that may have openly expressed doubt as to the Neubauer version of Tripoli 1933 was Bill Boddy in the September 1969 issue of Motor Sport. In “The Lottery Grand Prix, What Really Happened at Tripoli in 1933? The Editor Poses Another Motor Racing Question,”14 Boddy uses an article by Eoin Young and the mention of Tripoli in a book by Richard Garrett, both following the story line that the race was “rigged,” to launch a questioning of whether this could have been the case, reproducing the report of the race printed in the magazine in its June 1933 issue.

Boddy clearly casts doubt on the accepted story and wonders how the Neubauer version – as well as the re-telling by Young and Garrett – could be at such odds with what was reported in the contemporary report. There were responses to the article in the form of letters to the editor in the November issue, one from Johnny Lurani and the other from J.F. Cohen. Both cast doubt on the Neubauer version of Tripoli while making one wonder what else there was to the story.15

It was this article which piqued my interest in the Tripoli affair in the early 1970s. However, there were other things I was doing and I never gave it very much thought, other than to consider the Neubauer version very much open to question. Not until much later, 1992, did the story once again surface and in a very dramatic fashion.

In a coda to the 1933 season in A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing, Volume 3: 1932 – 1936, Betty Sheldon went Bill Boddy one better and laid out the results of the research that she had conducted into the Tripoli race. It was as if a thunderbolt had hit. Putting what Sheldon had found together with the thoughts of Bill Boddy, it became very clear that the Neubauer tale was little more than a cock-and-bull dinner story that he had devised for the entertainment of his readers. The thought was that the myth would now be laid to rest since what actually happened was now openly available.

What was dismaying was to find that the Neubauer-inspired myth continued to prosper and grow as if the research conducted by Sheldon and Boddy had never occurred. Once one knew what to look for, the story began to unfold and make sense. With the assistance of the scholars at The Nostalgia Forum on the Atlas F1 Web site, an earlier article on Tripoli was refined and later used by Christopher Hilton in his 1993 biography of Tazio Nuvolari.

Perhaps it is finally time to finally put the old myth to rest and properly give credit to Betty Sheldon and Bill Boddy for helping solve this mystery.16 In addition, give credit as well to Christopher Hilton for putting it print as well as being open-minded enough to look at the story from another view, one that was at odds with everything else he had read, and then accept it and print it.

However, let us examine two articles on the Tripoli race that were published at about the same time that the research that resulted in the above was being conducted. In other words, the two articles theoretically had access to the same materials, yet yielded entirely different results.

The first article, written by Mark Hughes, appeared in the January 2000 issue of Motor Sport.17 Given that scarcely thirty years prior to the article appearing in the same magazine that Bill Boddy questioned the Neubauer version of the race, the Hughes article is simply a regurgitation of what appeared almost exactly forty years earlier in 1960. All the familiar elements are in place – Rivio, Chiron, the characters in the special box for the lottery ticket holders (“....butcher from Milan, a frail old lady from Florence, a post office sorter, a salesman, a student.”), Varzi’s misfiring Bugatti causing Rivio much anxiety, the various delays in the pits, as well as Borzacchini in second place at the halfway point – a miracle considering that he had retired on the second lap with gearbox problems, with Borzacchini performing a major miracle by clouting a marker drum and bursting a tire on lap twenty-seven (although one must give Hughes credit for stating that the reason for retirement was given as “transmission”), Campari at the same point in the race stopping for a check of his suspension and retiring due to a “loose oil tank,” while Nuvolari pitted for fuel so as to allow Varzi to catch up and take the lead, then the Varzi Bugatti sputtering and slowing down until fuel from the reserve tank began to flow which allowed Nuvolari to catch up and pass Varzi, but Nuvolari then stopped once more for fuel as he entered the finishing straight, allowing Varzi to sweep by for the victory as Nuvolari gently crossed the finish line in second, with Chiron also in the mix of things at the finish.

All this was complete rubbish,18 of course, being even more so because it apparently never entered Hughes mind to search the archives at Motor Sport for anything on the race. I never received even a squeak from the editor, Andrew Frankel at the time, when I wrote him to politely point out what a load of bad history this article was. That Motor Sport had published an article on the Tripoli race meant that it would be a very long time before another article on the race would ever appear.

Not long after the Hughes article appeared in Motor Sport, an article on the Tripoli races appeared in Vintage Racecar Journal & Market Report and written by Robert Newman.19 Although the article was intended to cover the entire span of the Tripoli races, the centerpiece of the article was the 1933 race, of course. Newman has the drawing three days prior to the race, allowing Rivio – again – to fly to Libya to contact Varzi and make a deal to split the winnings if he could arrange to guarantee the result with the assistance of several of his friends. Newman refers to the events on race day as a “ham-fisted little drama.”

Once more the drama involves Varzi aboard a spluttering Bugatti in the closing stages, Borzacchini hitting an oil drum in the late stages and shredding a tire being forced to retire, Nuvolari in the lead on the last lap then stopping a few hundred yards away from the finish line to refuel, the task taking just long enough for the misfiring Bugatti of Varzi to pass Nuvolari for the lead, but the Alfa Romeo of Nuvolari taking station behind Varzi for second place as Varzi crossed the finish line for the victory.

Once again, complete rubbish, yet another retelling of the Neubauer story with a few elements of writer’s license used in the retelling of the tale. As in the case of the Hughes story, I contacted Vintage Racecar Journal & Market Report and pointed out, politely of course, that the article was scarcely an accurate portrayal of the race as it happened, simply another story lifted from Herr Neubauer. This time I did a response from the author. I had pointed out the article that I had written for Leif Snellman for his site, The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing, on the Tripoli race.20 Newman’s response was that although he had come across something like the tale I was supporting, in his opinion the weight of the evidence was behind what he wrote in the article. Plus, he said that the article I wrote was “self-referential” and, therefore, did not provide a valid counter-argument to what he had written.

That Newman provided no references in his article nor any in his response in support of the version of the events as he related them, the question must be asked as to exactly what evidence that he found which supported the Neubauer version, which was exactly what Newman provided in his article. Needless to say, even all these years later I would be quite interested to see what those sources were. Given that the article was written with plenty of time for Newman to avail himself of the same materials that I was, the question is why did he persist on using the Neubauer story without even mentioning that there might be alternative version of what happened.

I am curious as to what Newman thinks of what Christopher Hilton wrote regarding the race in the biography of Nuvolari that appeared in 1993. Does he discount what Hilton wrote? Is Vintage Racecar Journal & Market Report willing to finally publish a rebuttal to the Newman article?

Lest it seem that I am be singling out Newman and Hughes – which I am, of course – for any special criticism, they are simply examples of there being readily available information on the topic they chose to write about which was not consulted and which their editors were obviously unaware. In general, Newman does a credible job when it comes to his articles, but his audience is composed largely of those interested in historic racing, not racing history, which are two entirely different things.

Newman is a good writer and a mainstay of Vintage Racecar. He does have a wide-ranging interest in automobile racing history and often selects topics not within the mainstream which seem to get covered more than necessary considering that little new is ever generated. Likewise, Hughes is also a good writer, less inclined to write about history than Newman which is not surprising given his journalistic focus, the current Formula One scene.

For the record, the earliest Tripoli story based upon the Neubauer tale that I have found, although there might be others, of course, was written by Charles G. Proche and appeared in the February 1964 issue of Sports Car Graphic.21

Case History: John Glenn Printz and the Struggle for the Past

The A.A.A. Catastrophe: Arthur Means, Val Haresnape, Russ Catlin, and Bob Russo

|

No major sport has been so poorly chronicled, documented and recorded as “big time” American automobile racing. Very little information on it is readily available and much of what is easily obtainable is grossly accurate, incomplete and misleading in substance. It is very easy, for instance, to collect five times the amount of material or data on the Indianapolis 500 alone as compared to the remaining portions of a given season’s Championship activity…. By way of contrast to the American National Championship events, the European Grand Prix races generally have been given very detailed coverage since their birth in 1906.22 |

| John Glenn Printz |

|

The situation regarding National Championship racing is very strange with regard to the available information on the various races. It may be fairly said that for every 999 words written about the Indianapolis 500 race, none are written on any of the other races in the Championship..23 |

| Paul Sheldon |

Here is an excellent illustration as to what the American automobile racing historian is up against:

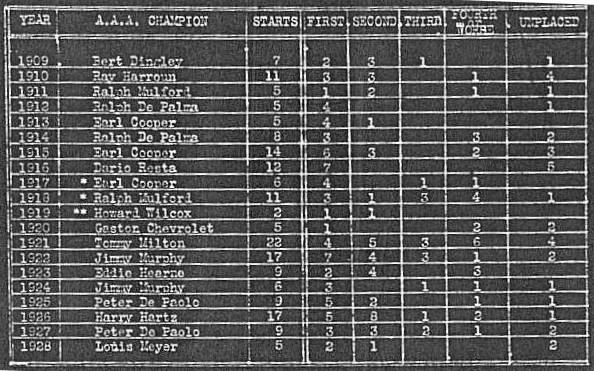

American National Champions24

The AAA Years

| 1902 | Harry Harkness | 1903 | Barney Oldfield |

| 1904 | George Heath | 1905 | Victor Hemery |

| 1906 | Joe Tracy | 1907 | Eddie Bald |

| 1908 | Louis Strang | 1909 | George Robertson |

| 1910 | Ray Harroun | 1911 | Ralph Mulford |

| 1912 | Ralph DePalma | 1913 | Earl Cooper |

| 1914 | Ralph DePalma | 1915 | Earl Cooper |

| 1916 | Dario Resta | 1917 | Earl Cooper |

| 1918 | Ralph Mulford | 1919 | Howard Wilcox |

| 1920 | Tommy Milton | 1921 | Tommy Milton |

| 1922 | Jimmy Murphy | 1923 | Eddie Hearne |

| 1924 | Jimmy Murphy | 1925 | Peter DePaolo |

| 1926 | Harry Hartz | 1927 | Peter DePaolo |

| 1928 | Louis Meyer | 1929 | Louis Meyer |

| 1930 | Billy Arnold | 1931 | Louis Schneider |

| 1932 | Bob Carey | 1933 | Louis Meyer |

| 1934 | Bill Cummings | 1935 | Kelly Petillo |

| 1936 | Mauri Rose | 1937 | Wilbur Shaw |

| 1938 | Floyd Roberts | 1939 | Wilbur Shaw |

| 1940 | Rex Mays | 1941 | Rex Mays |

| 1942 | No Racing - WWII | 1943 | No Racing - WWII |

| 1944 | No Racing - WWII | 1945 | No Racing - WWII |

| 1946 | Ted Horn | 1947 | Ted Horn |

| 1948 | Ted Horn | 1949 | Johnny Parsons |

| 1950 | Henry Banks | 1951 | Tony Bettenhausen, Sr. |

| 1952 | Chuck Stevenson | 1953 | Sam Hanks |

| 1954 | Jimmy Bryan | 1955 | Bob Sweikert |

This listing can be found a section named, ironically, “Auto Racing History,” which is part of the Deep Throttle site.25 Another site which carries race and season summaries for the AAA national championship events from 1909 onward which was developed and produced by Phil Harms, is Motorsport.com,26 which still provides the results used as source material for those interested in the American Automobile Association (A.A.A.) national championship.27 Once again, one can find a wealth on the A.A.A. national championship at the site Rumbledrome.com.28 This sort of listing can also appears, in various forms, in the United States Auto Club (USAC) yearbooks and many other publications that still sit on bookshelves all over the world. This listing is still accepted by many writers within the automobile racing community as being an accurate listing of the national champions.

Studying the list carefully, along with having a good knowledge of the AAA national championship, it quickly becomes apparent that the list should look something like this:

| 1905 | Barney Oldfield | 1916 | Dario Resta |

| 1920 | Gaston Chevrolet | 1921 | Tommy Milton |

| 1922 | Jimmy Murphy | 1923 | Eddie Hearne |

| 1924 | Jimmy Murphy | 1925 | Peter DePaolo |

| 1926 | Harry Hartz | 1927 | Peter DePaolo |

| 1928 | Louis Meyer | 1929 | Louis Meyer |

| 1930 | Billy Arnold | 1931 | Louis Schneider |

| 1932 | Bob Carey | 1933 | Louis Meyer |

| 1934 | Bill Cummings | 1935 | Kelly Petillo |

| 1936 | Mauri Rose | 1937 | Wilbur Shaw |

| 1938 | Floyd Roberts | 1939 | Wilbur Shaw |

| 1940 | Rex Mays | 1941 | Rex Mays |

| 1942 | WWII | 1943 | WWII |

| 1944 | WWII | 1945 | WWII |

| 1946 | Ted Horn | 1947 | Ted Horn |

| 1948 | Ted Horn | 1949 | Johnny Parsons |

| 1950 | Henry Banks | 1951 | Tony Bettenhausen, Sr. |

| 1952 | Chuck Stevenson | 1953 | Sam Hanks |

| 1954 | Jimmy Bryan | 1955 | Bob Sweikert |

While some may quibble about the about the inclusion of the 1905 A.A.A. National Motor Car Championship, it did exist, it did happen, and to the very best of our knowledge Barney Oldfield was the champion.29

The question becomes, of course, why does the second list differ from the first list?