Rear View Mirror,

Volume 8, No.4

Author

- Don Capps

Date

- December 29, 2010

Download

- RVM Vol 8, No 4 (PDF format, 936kb)

“Pity the poor Historian!” – Denis Jenkinson | Research is endlessly seductive, writing is hard work. – Barbara Tuchman

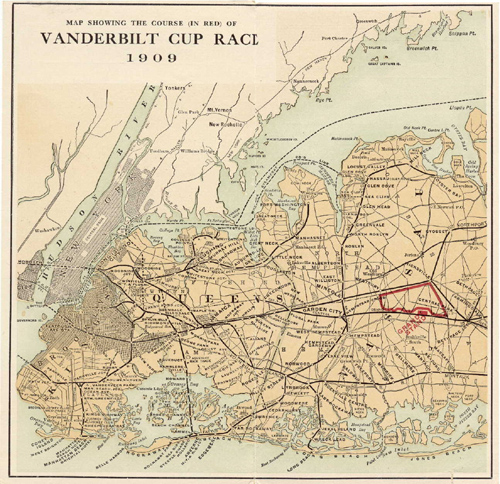

The 1909 Vanderbilt Cup Circuit in Relation to the New York City Area

I do not think that many have an appreciation for the proximity of the William K. Vanderbilt, Jr. Cup events held on Long Island to the New York Metropolitan area. This map shows quite well just how the location of the running of the 1909 event was situated to the metropolitan area. It is also informative to realize that this map also provides the locales for much of the racing in the area, both horse racing and automobile racing. The horse racing tracks for the Brooklyn Jockey Club (Gravesend), the Coney Island Jockey Club (Sheepshead Bay), Aqueduct Race Track, Morris Park, Brighton Beach, Empire City, and Belmont Park can be found on the map, although there is also the Empire City Race Track in Yonkers.

As far as automobile racing is concerned, there are the Brighton Beach track, the Morris Park track – which was originally for horse racing and then converted to use for automobile racing and then back to horse racing before being closed, the Empire City track in Yonkers, Jamaica where speed contests were held on the streets, the Coney Island Jockey Club track in Sheepshead Bay which saw some automotive competition – the Barney Oldfield-Jack Johnson Match Race being the best known – before it was torn down, with a planked-board speedway being built in Sheepshead Bay in 1915. There were also the Riverhead road races on Long Island and the Briarcliff race just north of the metropolitan area, plus the speed event on Staten Island in 1902 which set contests held on public roads back several years due to an accident which resulted in fatal injuries to spectators.

None of this, of course, even begins to consider the later races which would take place on the various small tracks that would sprout during theyears just before and after World War II era that witnessed the Midget Era and then the rise of stock cars. Nor should the sports car events on the area be overlooked, including those at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn as well as the Flushing Meadows event as the World’s Fair slouched to a close, to say nothing of the various Automobile Racing Club of America’s events held on Long Island.

Much remains to be written regarding automobile racing in the environs of New York during the early years of the Twentieth Century.

The 300 Mile Auto Race Classic

The Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition, Dallas, Texas

1

1

In the mid-Thirties, a possible revival of road racing seemed to be underway in the United States. Although the two runnings of the George Vanderbilt Cup races at the Roosevelt Raceway capture most of the attention, of course, during 1936 there were also the races held on the combined beach and road course at Daytona Beach and the all-but-forgotten eighty-eight mile road race held in conjunction with the Memphis Cotton Carnival in May.

The Memphis event benefited from the presence of the members of the American Automobile Racing Club of America, whose members made the trek from their usual environs in the Northeast to support the Southern event. The Memphis event had only eight starters, few of any contemporary fame, doubtless a major factor in its being lost in the mists of time.

There was also an effort underway around this time to build a permanent racing facility near Mines Field where several road races had been held. The new track was to be called the Los Angeles International Raceway. That the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association closely followed the story of the new Los Angles race track was taken as a sign that this was the apparent beginnings of an effort by the Triple-A to revive an interest in road racing. Or, perhaps, there was an interest on the part of some in reviving road racing which then gained the attention of the Contest Board.

The Los Angeles Raceway was scheduled to open on 29 November 1936 with a five hundred-mile event, followed by another such event on 22 February 1937.2 This announcement was followed by one stating that the November date had been dropped and that there would be a five hundred mile event held on 28 March 1937.3 Later, the Contest Board announced that there would be major events at the Roosevelt Raceway on 5 July and 6 September, Labor Day, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on 31 May, and an event during the Fall at the Los Angeles Raceway.

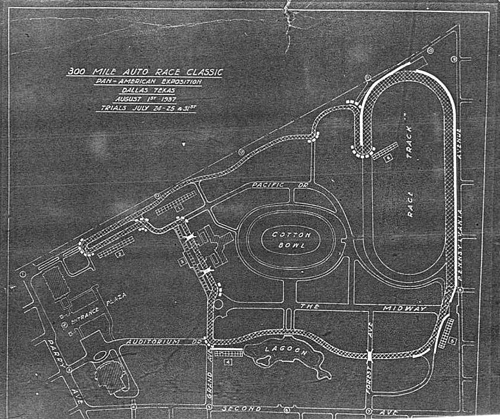

Then there was the road race to be held on 1 August in conjunction with the Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition in Dallas, which would utilize the Texas State Fairgrounds.4 The fairgrounds also held the Cotton Bowl and a one-mile horse racing track. The “Pan-American 300 Auto Race Classic” was being promoted by George P. Marshall, the same promoter for the Roosevelt Raceway events. Marshall was the Director General of the exposition.

The course was described as being “approximately two miles,” and would have the Cotton Bowl in the middle of the course. The purse was announced as $17,500, of which $15,000 would be divided among the first seven finishers and the remaining $2,500 would be split among the first five during qualifying. Qualifying was to be spread over three days: 24, 25, and 31 July. The first entry for the event was the MG Midget of Miles Collier.5

Soon, however, it was announced that the Dallas race was canceled.6 The Contest Board stated that by an agreement on 10 July 1937, between the Contest Board and the director of the Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition that the event was being dropped. The reason for the event was given as the refusal of “a group of prominent drivers to enter the contest unless the distance was drastically reduced.” An offer to reduce the distance to 250 miles as offered by the promoter against that of two hundred miles by the drivers was dismissed as not being worth the expenditure by the promoter.

It is interesting that the story of the Los Angeles Raceway is rarely given much thought nor the saga of the Dallas event. That the 1937 Labor Day event at the Roosevelt Raceway was scheduled, but never held is usually another surprise to many when it is brought up. It would have been interesting to see what might have happened had things gone differently.

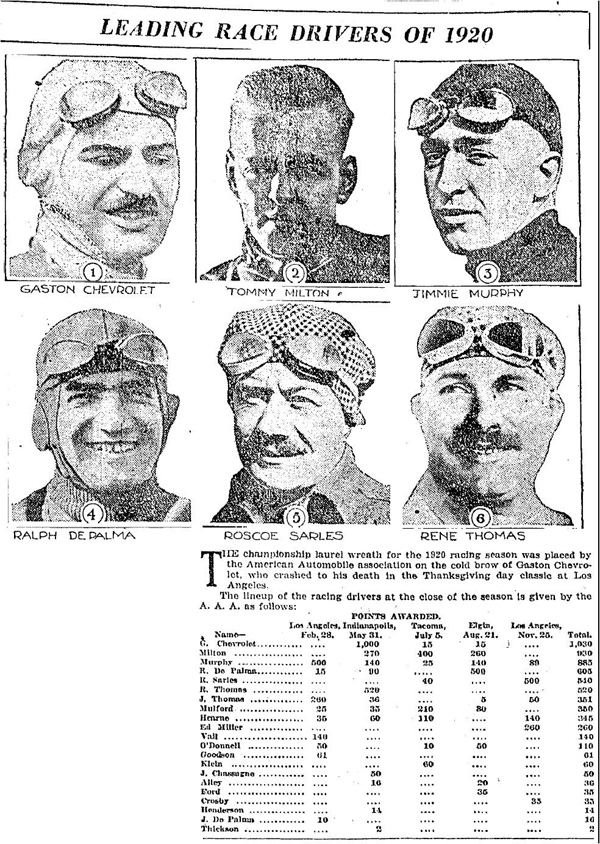

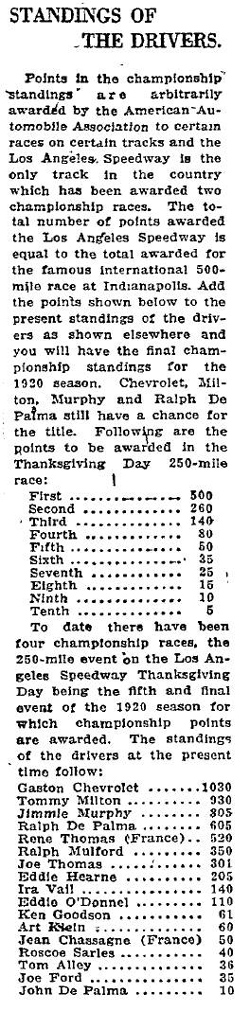

Contemporary Results of the 1920 A.A.A. Championship

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

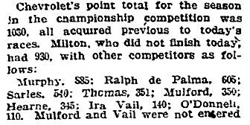

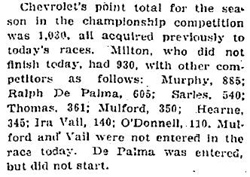

Not meaning to continue to try to squeeze any more glue out of a seriously dead horse, but here are five (5) contemporary sources which should nail the coffin firmly shut on the crackpot notion that Bob Russo – and Russ Catlin – tried peddle about the 1920 National Champion being Tommy Milton.

11

11

An Addendum:

The 1936 Daytona Beach A.A.A. Stock Car Race

Omitted through simple oversight on my part as part of the look at the March 1936 running of the A.A.A. at Daytona Beach12 was the entry list for the race.13 It makes for some interesting reading and I apologize for somehow not providing it in the original article.

| Car No. | Make | Driver | Entrant |

| 14 | Ford | Walter Johnson | D.L. Moody |

| 5 | Dodge | Wm. Schindler | H. Atkinson |

| 22 | Ford | “Hick” Jenkins | H.R. Dixon |

| 19 | Ford | Sam Purvis | Sam Purvis |

| 15 | Ford | Dan Murphy | Carl Purser |

| 17 | Ford | Ed Eng | Don Suttle |

| 29 | Auburn | John Rutherford | John Rutherford |

| 16 | Ford | Albert Cusick | Albert Cusick |

| 9 | Ford | Wm. Lawrence | Wm. Lawrence |

| 11 | Ford | Lou Campbell | L.S. Campbell |

| 21 | Ford | Bill Sockwell | Bill Sockwell |

| 3 | Chevrolet | B.J. Gibson | B.J. Gibson |

| 1 | Willys 77 | Langdon Quimby | Langdon Quimby |

| 4 | Willy 77 | Sam Collier | Sam Collier |

| 24 | Ford | Doc Mackinzie | G.D. Mackenzie |

| 18 | Ford | Ben Shaw | E.D. Parkinson |

| 6 | Ford | Bob Sall | Rudy Adams |

| 26 | Ford | Tommy Elmore | Thos. Elmore, Jr. |

| 20 | Oldsmobile 8 | Ken Schroeder | Floyd A. Smith |

| 2 | Auburn | Bill Cummings | M.J. Boyle |

| 25 | Ford | Al Wheatley | Al Wheatley |

| 12 | Ford | Al Pierson | Al Pierson |

| 27 | Ford | Jack Holly | Jack Holly |

| 28 | Ford | Virgil Mathis | Dan H. Stoddard |

| 8 | Ford | Gilbert Farrell | C.A. Hardy |

| 7 | Lincoln Zephyr | Major A.T.G. Gardner | A.T.G. Gardner |

| 10 | Ford | William France | Isaac Blair |

| 23 | Ford | Milton Marion | Milt Marion |

The bottom of the page listing of the entrants carries this bit of information: “1936 National Championship Beach and Road Race.”

The flag signals used during the race are also listed:

| Green | Start of race; Course is clear. |

| Yellow | Caution; Bring car under control and reduce speed to 50 miles per hour. |

| Orange with Blue Center | Competitor is attempting to overtake you. |

| White | Report at your pit on the next lap. |

| Red | Danger; Stop. |

| Blue | You are entering your last lap. |

| Checker | You have finished. |

More Sighs of the Apocalypse:

Notes from the Ashepoo & Combahee Drop Forge Tool Anvil & Research Works

Society of Automotive Historians. Recently, I had the privilege of attending the annual meeting and awards banquet of the Society of Automotive Historians held at the Hershey Country Club in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Although I have been a member of the SAH for several years now, due to my usual adventures with the American military establishment I have not been able to attend many – as in any – of the SAH meetings since I made the decision to sign on with the outfit. It was a delightfully low key affair, very much in ambiance and style the sort of thing that I recall from my days in the hallowed halls of the academe. Which is to say that it was exactly the sort of slightly askew sort of affair one expects from an organization that is largely composed of those from the academic world. Needless to say, I very much enjoyed it.

The Society of Automotive Historians uses this meeting as the venue to hand out most of its annual awards – along with a separate meeting held in Paris during February, in conjunction with the Retromobile show, which is held for the European members and to present the non-English language awards. It was interesting that the two books receiving recognition the English language category, Storied Independent Automakers: Nash, Hudson and American Motors by Charles K. Hyde and Maxwell Motor and the Making of the Chrysler Corporation by Anthony J. Yanik, recipients of the Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot Award and the Award of Distinction respectively, were published by the Wayne State University Press.14

The E.P. Ingersoll Award is presented as recognition for “excellence in presentation of automotive history in other than print media.” This covers the gamut from film to the internet, which is really quite a span. Most of the previous awards have been for projects using visual media, film or video, but this year for the third time an internet site won the award: Coachbuilt.com. Personally, I had hoped that Leif Snellman’s site, The Golden Age of Grand Prix Racing, would win, but there is, I must admit, a strong inclination for things truly automotive to be recognized by the SAH, recognition of things strictly related to automobile racing still being an exception, which is to be expected given the focus of the vast majority of the membership.

Perhaps the most noteworthy recognition, for me at least, was the presentation of the James J. Bradley Distinguished Service Award, which is an award recognizing the library or archive involved in the preservation of historic materials relating to motor vehicles around the world deserving special recognition. The 2009 award went to the Automotive Research Library of the Horseless Carriage Foundation, located in La Mesa, California, which is in the San Diego area. For me, this was wonderful because thanks to this particular effort there are now volumes upon volumes of The Automobile, Motor Age, The Horseless Age, and other American automotive journals from the early Twentieth Century now available on the internet. This is an excellent example of the value of the Digital Library concept. Half a world away from the Research Library of the HCFI in La Mesa, I was able to access and use materials for my research even though I was in the Middle East. I would love to see the International Motor Racing Research Center at Watkins Glen to also receive this recognition.

During the dinner itself, I sat at the same table with Dr. Joe Freeman, the man behind Racemaker Press. Dr. Freeman is also the owner of the Bob Russo archives as well as several other collections. It is possible that, thanks to Dr. Freeman, I might have the opportunity to finally take a look at the Russo collection and find out just exactly what is in the collection, having heard several conflicting tales as to its contents. Only time – and a trip to Boston – will tell.

2010: Armageddon out of here. The 2010 automobile racing season pretty much came and went without much in the way of any real interest on my part. Well, not exactly without any interest. I was intrigued that the Indy Car Series might actually adopt the Delta Wing for its next baseline design. I even laid aside my usual skepticism and – regrettably as it turned out – cynicism regarding what has been a basically dysfunctional series for years and years. It was fascinating and downright amazing that those running the series would even consider such a design, much less that it could be a true contender.

That there could be only one design that would “win” bothered me a great deal. While there was once upon a time a large degree of merit in the one-design or “spec” series notion, that time would appear to be long past. That what purports to be a major national – I find it difficult to consider it “international” in the older meanings of that term – open-wheeled series has long been reduced to a “spec” series is somehow rather pathetic. This is not to necessarily to belittle or deprecate those competing in the series, but rather that there are consequences to actions, even those made years in the past. That those consequences are inflicted upon those removed from those events is why those in automobile racing are generally concerned only with the Here And Now, history being, perhaps, a season or so in the past and relevant only for matter pertaining to car set up rather than any larger meanings.

Of course, I should have known better to even allow myself to find any enthusiasm for the Delta Wing car. Unlike the other designs, it looked different – and did so in a good way. When they chose what can only be charitably described as more of the same blandness – the whole nonsense concerning proprietary “aero packages” is enough to make one wonder just how long the series has left – rather than the Delta Wing, I realized that I had been taken. Despite the genuine enthusiasm for the Delta Wing by those such as Gordon Kirby, I should have realized that it was never a viable option for those on the interestingly named “Iconic” committee which made the choice.

When it counted, they simply lacked the guts to make the hard choice.

Harsh? Yes.

True? Absolutely.

The Indy Car crowd has, by and large, rationalized the selection that was made, in reality a rejection of the real choice that the Delta Wing reflected.

One of the great rationalizations that is lamely trotted forth and repeated endlessly as to why people state that they like automobile racing is the technology involved in racing. Given how much of the technology in automobile racing is anything but advanced or even that interesting or has any practical application, I tend to curl my lip and snarl my dissent at such pedestrian excuses. It is my major concession to the lesser angels of my nature, I must admit. All the hype concerning the technology in racing is, at best, smoke and mirrors, polite exaggerations or wishful thinking, infused with not a small dose of a willful suspension of belief.

As the season wound down, I found that it was difficult to muster much in the way of any enthusiasm for any of the four finalists in the Formula One World Championship – which is perhaps best thought of as Formula Ecclestone given that what we now have is largely the result of his, well, ego and raw use of power.

The same lack of enthusiasm could be said for the three finalists in the Sprint Cup Series. The last remnant of my interest in contemporary automobile racing has long been with the NASCAR premier series, with the Indy Car series trailing at a remote distance. However, I am finding that there is less and less of interest for me whenever I watched the events this season. True, for much of the past half dozen years I have been in the Middle East and this has been a not insignificant factor in my dwindling interest in contemporary automobile racing.

I would suggest, however, that it is difficult to impossible to imagine automobile racing in 2011 being any “better” – perhaps “interesting” or “appealing” would be better words? – than it was in 2010 or even 2008 or 2004, these being the last time I witnessed full racing seasons I was around to consider at home.

On the other hand, it often seems that the interest in the history of automobile racing is becoming more and more a matter of the trivial and the superficial. Those producing works that reflect thinking in historical terms appear to becoming fewer rather than more prevalent.

Something to think about.

Notes

- Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume XII Number 3, 3 May 1937.

- Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume XI Number 7, 9 July 1936, p. 1.

- Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume XI Number 10, 29 October 1936, p. 2.

- Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume XII Number 3, 3 May 1937, p. 2.

- Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume XII Special Bulletin, 13 May 1937, p. 3.

- Official Bulletin of the Contest Board of the American Automobile Association, Volume XII General Bulletin, 12 July 1937.

- H.A. Tarantous, “Another Year of Racing,” Motor Age, January 1921, p. 62.

- “Two Killed, One Dying In Auto Race Crash,” Boston Daily Globe, 26 November, 1920, p. 1.

- “Gaston Chevrolet Killed in Big Auto Race,” Chicago Tribune, 26 November 1920, p. 1.

- “Leading Race Drivers of 1920,” Chicago Tribune, 30 January 1921, p. D5.

- “Standings of the Drivers,” Los Angeles Times, 21 November 1920, p. VI 1.

- “Daytona Beach, 1936,” Rear View Mirror, Volume 8 Number 2.

- William P. Lazarus with J.J. O’Malley, Sands of Time: A Century of Racing in Daytona Beach, Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2004, p. 83.

- It was also not very surprising to note that the Wayne State University Press also published MC5: Sonically Speaking, A Tale of Revolution and Rock ‘n’ Roll by Brett Callwood (2010).