My racy Valentine

Author

- Mattijs Diepraam

Date

- June 8, 2009

Related articles

- 1947 Italian Championship - The race when Nuvolari waved the steering wheel at the crowd and a forgotten Championship, by Alessandro Silva

- Alfa Romeo 158 - The voiturette that became the Grand Prix car to beat, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas

- Alberto Ascari - Cursed natural talent, by Mattijs Diepraam/Felix Muelas/Leif Snellman

- Lancia D50 - Tipo D.50 case history, by Don Capps

- Maserati V-8R1 - German influence, by Leif Snellman

- Tazio Nuvolari - Mantua's Great Little Man, by Leif Snellman

- Raymond Sommer - The heart of a lion, by Felix Muelas/Michael Müller

- Luigi Villoresi - Ascari's mentor, by Leif Snellman/Robert Blinkhorn

- Jean-Pierre Wimille - The uncrowned king of the forties, by Mattijs Diepraam

Who?Tazio Nuvolari What?Cisitalia D46 Where?Parco del Valentino When?1946 Coppa Brezzi |

|

Why?

A long time ago, when the industrial revolution was gaining speed, cities created lush and lofty park areas to function as green lungs, havens of peace and quiet for their citizens to dwell in the middle of fast-moving and rapidly expanding metropolitan life. And yet, in so many places across Europe, city parks were soon found to provide quite the opposite of peaceful recreation and botanical beauty. From Bois de Boulogne to Montjuich Park, from Leipzig Stadtpark to Parco del Valentino – they all proved to be an exciting environment for a motor race. We visited Turin’s Valentino Park to see why.

The Parco del Valentino was opened by the city of Turin in 1856. It’s situated on the left bank of the Po, stretching for over 30 hectares along the country’s longest river, and was Italy’s first public garden. The focal points of the park are the Castello Valentino, the former royal palace, around which the park was originally laid out by Carlo Cognegno di Castellamonte in the 17th century before it received its 19th-century makeover by Frenchman Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, and two mock medieval edifices, the Rocca, a replica fortress built in the 17th century, surrounded by the Borgo Medievale, a fake middle-age village created as a part of the first Italian Arts & Crafts exhibition of 1884. Since then the Valentino has been the site of many fairs and flower shows. The botanical garden, the rock garden and the rose garden are all results of those exhibitions. The Torino Esposizioni, once the realm of Turin’s auto salon, now holds a temporary display of the Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile, which has been closed for renovation for several years already.

The Rocca.

Entering the Borgo.

Inside the Borgo.

The vast majority of today’s joggers and sunbathers won’t be aware of the fact that this romantic French-style park was once the scene of a furious annual spectacle that used the park’s main promenades as a playground that wasn’t quite as innocent as a leisurely game of soccer among friends. To the trained eye, though, it’s obvious.

It’s the width of these roads. The curvaceousness of the curves. The crests and drops of the parkways, against a luscious backdrop of flowers, trees and the Po river. It’s perfect for a racing circuit. For several circuits, in fact.

The Valentino Park circuit doesn’t exist. Its lay-out was adapted constantly, from the first event in the thirties to the last one in the fifties. It didn’t happen with a change here or there, these changes weren’t varying on the same basic theme. Almost every thoroughway in the park – and even beyond – was used at least one, and often in both directions as well.

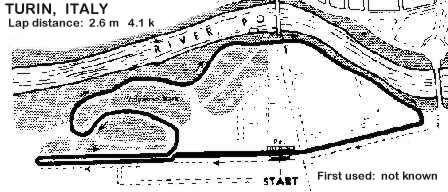

The 1935 layout.

In 1935, on the bright summer’s day of July 7, the first Gran Premio del Valentino was held on a circuit with its main straight outside the park itself, on the Corso Massimo d’Azeglio, with an up-and-down section alongside the park’s western boundary. The part running alongside the Po from the Borgo back to the main straight, along the Viale Marina d’Italia, also left the park area. The park section comprised the sloping parkway around the rock garden.

Coming down from the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli towards the Viale Virgilio and the rock garden.

Heading towards the rock garden and the Borgo.

On the Viale Stefano Turr, towards the Po and the south side of the park.

A bit further on.

Going underneath the Corso Dante onto the Viale Marina d'Italia, the road alongside the Po towards the most southern point of the 1935 circuit.

The race was held on the same day as the Marne GP, so the big teams had to split their efforts. Ferrari sent a quintet of Tipo Bs for Nuvolari, Brivio, Trossi, Pintacuda and Tadini to Turin while Chiron and Dreyfus were sent to Reims to take up the challenge of Sommer’s private Alfa. Scuderia Subalpina allowed the Maserati V-8RI to take its debut at the French event in the hands of Étancelin and sent Farina and Siena to Turin in a pair of 6C-34s, with Dusio in an 8CM. Variety was provided by Taruffi in a works Bugatti T59 while the field was completed by a legion of privateer Alfas and Maseratis. The Ferrari cars proved to be unbeatable, Tadini, Trossi and Nuvolari winning their heats from pole, with the latter beating Brivio and Pintacuda in the final.

The 1937 layout.

The 1937 race, run on April 18 under the moniker of the GP Principe del Piemonte, used an entirely different circuit. Now using a shorter stretch of the Corso d’Azeglio the track entered the park at its main entrance in front of the Royal Palace, then around the botanical garden onto the Viale Virgilio. Instead of charging past the rock garden and the Borgo, the circuit hairpinned back up to the hilly Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli where two years earlier the cars raced in the other direction. It then curved eternally towards the Viale Carlo Ceppi before crossing the squadra for a short blip down the other side of the Corso d’Azeglio, in front of the Torino Esposizioni buildings.

The long and winding north-side corner around the botanical garden. This is looking back towards the Viale Pier Andrea Mattioli.

Looking to the other side, onto the Viale Virgilio.

The Viale Virgilio towards the castle.

A bit further on.

This time the race was one big 60-lap event, again dominated by the Ferrari-entered Alfa Romeos. Four 12C-36s were sent to Turin for Brivio, Farina, Trossi and Nuvolari, the main opposition coming from Wimille’s works Bugatti. Just nine cars made the start, and Ferrari’s main man Nuvolari wasn’t among them as he’d crashed heavily during practice. He only returned from hospital in a plaster corset three days later, so Pintacuda was called in to replace the Mantuan. Eventual winner Brivio was the only Ferrari driver not having to stop for water to relieve his Alfa from radiator problems, making him a comfortable winner over Farina and Trossi.

The castle on the right.

Looking back onto the Viale Virgilio.

The hairpin turn back onto the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli.

An overview with the Viale Virgilio on the right and the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli on the left.

The supporting voiturette event, the Circuito di Torino, ran over 40 laps, with two works Maseratis for Dreyfus and Bianco leading the entry. It was Bira’s ERA, however, that took pole. At the start, the Maserati works cars shot away into the lead with Bira in hot pursuit. Bira first dragged past Dreyfus on lap 4 to go after Bianco, who made his car very – some would have said unallowably – wide. Then the Italian lost his goggles and the Siamese forced his way through. It was all in vain since he had to retire with a broken gearbox only a few laps later. The hero of the race wasn’t among the front-starters, however. Norwegian ice-racing king Eugen Bjørnstad had spun his ex-works ERA on lap 2 and looked out of contention. But he then employed his customary aggressive driving style to slide through the entire lead and take the lead 5 laps from the end. It was Bjørnstad’s first and only win off Scandinavian soil – or rather, ice.

The climb towards the top on the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli.

At the top of the hill on the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli.

Turning back to the Viale Carlo Ceppi.

On the Viale Carlo Ceppi.

Park races were among the first to be revived after World War II. Indeed, Bois de Boulogne saw the first motor race after Europe’s liberation, and the circus returned to Turin one year later. Yes, a circus, literally this time, since the Coppa Brezzi was the overture to Piero Dusio’s Cisitalia D46 ‘racing circus’ that would be travelling the world in 1947 but found an early demise after its display in the Egyptian desert. Here, the D46 would see its debut in the sportscar race named after Andrea Bretti, Dusio’s sportscar ace who died during the war. Because of the D46 the race was opened to unsupercharged single-seaters with a maximum capacity of 1500cc. Turin was Cisitalia’s hometown, after all. The D46s, all raced by name drivers attracted by Dusio’s generosity, duly occupied the first rows of the starting grid. While it was Dusio himself who won ahead of fellow Cisitalia drivers Cortese and Chiron, the show was undoubtedly stolen by none other than Tazio Nuvolari. The ageing showman managed to work loose the car’s steering wheel when its hinges broke under the stresses ‘Nivola’ had applied to them. Never one to give up, he proceeded at great speed across the main straight, waving the wheel at a crowd that understandably went totally mad.

The Viale Carlo Ceppi, now half closed off by a gate.

Entering the square.

Looking back towards the Viale Carlo Ceppi.

The main event was the third GP del Valentino and it was consummately won by the two Alfa Romeo 158s still in the race, Varzi leading Wimille, both of them two laps ahead of their nearest rival Raymond Sommer in his Maserati. Three weeks later many of the same cars and drivers were found in another park, Parco Sempione, for the Circuito di Milano, the final going to Trossi ahead of Varzi and Sanesi, all again on Alfettas. The two races are often seen as the first two ‘Formula 1’ races, since the category had just been coined by the CSI.

The square.

The park's main entrance. Here the cars would re-enter the park from the Corso Massimo d'Azeglio. In 1948 and 1955 they would just run across it on the right-hand side.

Viale Pier Andrea Mattioli, with the entrance to the botanical garden on the right.

The following year, the Turin GP was held late in the year, as a sportscar event. After having made its debut in the Coppa Acerbo at Pescara on October 12, Raymond Sommer gave the new Ferrari 159 S its first victory at Valentino Park.

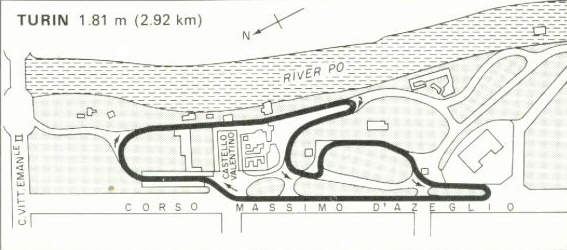

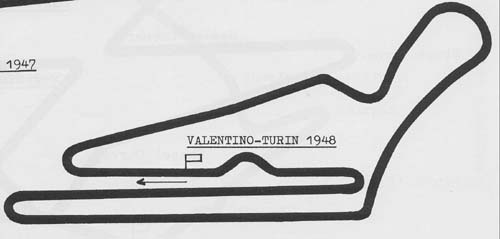

The 1948 layout.

The F1 cars were back on September 5, 1948, but not just for the fifth GP del Valentino. This time, the venue was no less than the 18th Italian GP as well, and the Alfas of Wimille and Trossi were again leading the entry. The usual Maserati (Villoresi, Ascari, Parnell) and Talbot-Lago (Rosier, Étancelin, Comotti) opposition were joined by Sommer, Farina and Bira giving the new Ferrari 125 its first outing. The single-seater version of Ferrari’s first car of his own, the 125 S, shared the same Colombo-designed 1.5-litre V12 with its sportscar predecessor and managed to claim third place in the race, Sommer one lap down on Villoresi and two laps down on winner Wimille. Sommer was the first non-Italian to race a works Ferrari – quite a contrast to the last few decades when this has been the rule rather than the exception.

The top end of up-and-down main straight on the Corso d'Azeglio, at the junction with the Corso Vittorio Emmanuele.

On the Viale Virgilio, passing the junction with the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli, this time going straight through.

Having past the Borgo, the track took a sharp right onto the Viale Matteo Maria Boiardo, towards Torino Esposizioni.

The fountains at the back of Torino Esposizioni.

The circuit was a 4.8km track expanded from the 1937 layout. It again used the Viale Pier Andrea Mattioli and the Viale Virgilio around the botanical garden but blasted straight through past the rock garden and the Borgo to cut back to the Viale Matteo Maria Boiardo. At the end the track would spill out onto the Corso Massimo d’Azeglio. Here a huge straight covering the entire length of the park westside border led to a narrow hairpin turn at the upper end of the Corso where the same stretch was done again on the other side of the Corso, in the opposite direction of course. Much more of a high-speed layout than the others, it was obvious that this played into the cards of the powerful Alfettas.

Approaching the square.

Having run the entire up-and-down straight on the Corso d'Azeglio, the cars would turn back on the north side of the square onto the Viale Medaglie d'Oro. This is looking back onto the Viale Medaglie d'Oro on the junction with the Viale Diego Balsamo Crivelli.

The track continued on the Viale Carlo Ceppi towards the park's main entrance and the botanical garden.

The 1952 Turin GP went to Luigi Villoresi. The sixth GP del Valentino, now moved to April, was another Ferrari whitewash but now the Commendatore swamped the podium with three cars of his own manufacture, Villoresi in the 375 F1 car easily outclassing the F2 examples of Taruffi and Fischer. Along with Albi, Goodwood, Dundrod and Boreham, the park was among the few international events still open to F1 cars in the first year that the big World Championship events all switched to F2 regulations.

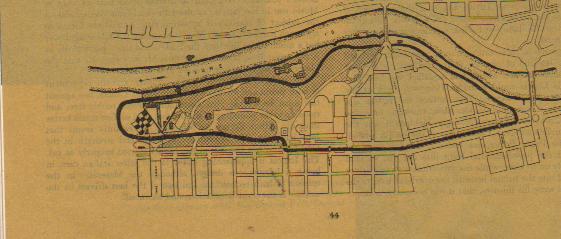

The 1955 layout.

Grand Prix racing returned to the Valentino one more time. On March 27, 1955, an even faster track was used, combining the 1935 back stretch along the Po with the 1948 ‘infield’ section. Rather melancholically, the race went to Alberto Ascari and the Lancia D50, not long before the two took to water at Monaco and Ciccio’s premature death at Monza four days later caused Lancia’s Grand Prix efforts to stall. Rather happier days still at the Parco del Valentino then…

All peace and quiet on the promenade along the Corso d'Azeglio.

With more purpose-built circuits being created and the number of non-championship races declining all through the fifties time had run out for Valentino Park as a venue for motor racing of the highest calibre. Now, over half a century later, there is nothing to remind you of this noisy and exciting part of the park’s history.