The Indy 1964 second-lap disaster - Closing in on the truth

Part 2: Before May 30, 1964

Author

- Henri Greuter

Date

- October 25, 2010; with December 8, 2011 additions

Related articles

- The Indy 1964 second-lap disaster - Closing in on the truth, by Henri Greuter

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 3: May 30, 1964

- Part 4: Since May 31, 1964

- Part 5: On Black Noon by Art Garner

Who?Eddie Sachs What?Halibrand Shrike-Ford 'American Red Ball Special' Where?Indianapolis When?1964 Indianapolis 500, practice |

|

Why?

- About Dave MacDonald and Eddie Sachs

- The 1964 Mickey Thompson Sears Allstate Special

- An evaluation of the 1964 car, compared with the 1963 version

- The 1964 “500” practice and qualifying

About Dave MacDonald and Eddie Sachs

This site doesn’t intend to become the best source of info on Dave MacDonald available on the Internet. But a brief biography about him is appropriate. (5)

Dave was born on July 23rd, 1937. He was married to Sherry and together they had two children, a son Rich and a girl Vicky, who were aged 7 and 5 in May 1964, respectively.

Dave started his racing career in drag racing in 1956. In 1960 he started to drive sports cars. His first race came at Willow Springs driving a Corvette and he won the production class. He was then picked up by Carroll Shelby and became a factory driver for the Cobra team. His best year was 1963, driving a King Cobra, and he won important races at Laguna Seca and Riverside. That year he also carried out some initial tests for Mickey Thompson at Indianapolis.

For 1964 he was signed up for the Mercury stock car racing team and finished 10th in the Daytona 500 that year. Dave and Mickey knew each other from the drag racing world and both came from the same town, too. When Dave was offered the drive he told to Dick Mittman (editor of the Indianapolis Time) that he knew he could not win the race and had still a lot to learn.

Thompson regarded MacDonald as one of the most talented drivers he knew, capable of sorting out the car and telling what was wrong with it, a fact that helped him to get the drive with Mickey’s stable.

Given the fact that fate has linked Dave and Eddie, here is a brief biography on Eddie Sachs as well. (5)

Eddie was born on May 28th, married to Nance and father of a 2 year old boy. His first time at the Speedway was in May 1953 after having built a reputation in sprint cars. But when he spun early on in a drivers test he was asked to gain more experience before trying again. He passed the test in 1956 but was first alternate that year. Still he won a USAC race that year. One year later he qualified second at Indianapolis.

At the beginning of the sixties Eddie’s career entered a zenith. He became the pole winner in 1960 with new track records but eight days later Jim Hurtubise smashed his fresh records. In the race he led 21 laps and was classified 21st when his car retired after 132 laps. In 1961 Eddie won the pole yet again and finished second after making a late pit stop for a fresh tyre with 3 laps to go. Some people suggested that Eddie should have tried to nurse his car home and take the risk since victory was at stake. Eddie however felt that it was his life that was on the line so he took the decision not to take unnecessary risks.

In 1962 his qualifying attempt was late and he was 27th in the field but he managed to work his way up to third. In 1963 he started tenth and was in fourth place at the end of the race till he spun out, allegedly on oil lost by Parnelli Jones. He ended up in a big argument with Parnelli, which eventually ended in a physical fight, As a result, Eddie was put on probation for a year.

Eddie was convinced that the rear-engined cars that had appeared in the past years were the way of the future and he wanted such a car for 1964. The car owners he drove for since 1963 provided him with such a car.

Eddie was a colourful person, never lost for words. Given a chance to speak, it was difficult, if not impossible to stop his vocal waterfall, known for his sense of humour. He was well respected, well loved and had earned the nickname “the clown prince of auto racing”

But he was also known for being almost in tears during the traditions preceding the start of the “500”. He had promised his wife that he would quit racing once he had won Indianapolis.

Dick Sommers was one of the team owners Eddie drove for in 1963 and 1964. In his own biography, Sommers wrote one line which must have met much approval with all people who cared for Eddie. Sommers described the USAC board hearing about the fist fight between Eddie and Parnelli. He concluded with:

“I’ve often regretted not having yelled and screamed at the USAC board that day in the hope that Eddie would follow suit. He probably would have been suspended for a year and might be still around.” (4, p.32)

The 1964 Mickey Thompson Sears Allstate Special

Few cars, if any, have earned such a bad reputation at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as these cars. The Novis had a reputation of being jinxed and the 1946-built FWD Novi chassis killed two beloved, experienced veteran drivers. But this particular car was twice holder of the 1 and 4-lap track records (and currently still the 4-lap track record holder for front drive cars!) and, like just about every Novi, was popular with the crowd as well. The STP Turbine cars of 1967 and ’68 were also very much disliked by the majority of the race fans in their active years but that was because of their engine technology and their efficiency. In later years the cars gained a lot of credibility because of their being innovative and revolutionary. The 1964 Thompson, however, never gained any popularity for whatever reason with the crowd or just about anyone else.

The 1964 car was based on a chassis that had been introduced one year before. At that time, the rear engine revolution had just started seriously with the arrival of the Colin Chapman-built Lotus powered by Ford. American car builders, however, remained loyal to the traditional Offy-powered, front-engined `roadsters`. The only exception was Mickey Thompson.

Thompson had entered the 500 for the first time in 1962 with a car designed by John Crostwaithe. This was a car based on the rear-engined Cooper design, fitted with a 4.2-litre Buick pushrod V8 engine. Although several cars were entered, only rookie Dan Gurney managed to qualify one. Gurney was an early retirement in the race but is credited as having told the car to be quite good and being rather positive about the team and its commitment to race the car. (9, p.122)

One of the 1962 cars of Mickey Thompson. This is Chuck Daigh’s rear-engined Thompson-Buick.

He failed to qualify but Dan Gurney made the race in another Thompson entry.

(copyright First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

In 1963 Thompson entered several cars, three of which were very low-built, flat and wide cars, rear-engined again, powered by a 4.2-litre Chevrolet pushrod V8. The most remarkable detail about these cars were their tiny, 12-inch diameter tyres to reduce the air resistance. In order to give the tyres enough area to put on the track, they were wider than usual to compensate. The car quickly earned the nickname 'Rollerskate'. The chassis were tube frames.

Another driver practicing the car was Bill Krause, who had been successful with, among others, Maserati sportscars. Maserati historian Willem Oosthoek interviewed Krause about his career. Krause had the following to say about his experience with the Thompson:

WO: After Daytona 1963 Chevrolet closed the door but you still had Mickey’s Indianapolis program.

BK: The Indy cars constructed by Mickey had those little controversial 12 inch wheels and we tested them at a Firestone test track in Texas, a 7-mile oval in the middle of the desert. But that track did not offer enough high friction so we couldn’t find out much about the adhesion and handling characteristics of those tires. Firestone was nervous about their use and made real hard rubber compounds for them. It showed! When they let go during practice at Indy there was no warning. When I spun the car I had no clue. It was just gone, lost traction. Usually you have a little warning. It was zero. I was straight and I was sideways. I spun in turn 1 and ended up in turn 2, never touching the brakes. And I would not have hit anything if Roger McCluskey’s roadster hadn’t run into me.

WO: Nobody could qualify those cars. Graham Hill couldn’t. Masten Gregory couldn’t.

BK: Well actually Duane Carter did. But there was too much confusion in the team. Mickey had 6 cars entered. Three days in a row, when I was doing 200 mph on the back straightaway, the hot oil would come out and the wind would blow it in my face and goggles. I lost confidence. I didn’t feel comfortable. I probably could have qualified the car but I couldn’t have driven it with 32 other guys because I couldn’t tell where it was going. So I decided to pack up and go home to California. At that point I decided I should stick with making a living and pursue my business interests. I had lost my motivation. Indy changed my attitude. I did race after that but it was never the same. (32)

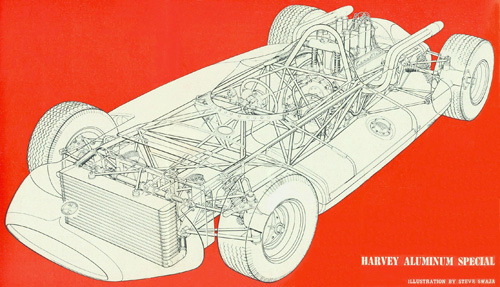

A cutaway drawing of the 1963 Thompson-Chevy.

One of the cars had a chassis built out of the superlight metal titanium. This car was assigned to Masten Gregory, who failed to qualify the car.

This is the titanium chassis driven by Masten Gregory who failed to qualify the car for the race. (copyright First Turn Productions LLC, used with permission)

World champion Graham Hill also practised with a car but failed to qualify as well. The only driver managing to qualify a 'Rollerskate' (15th) was veteran Duane Carter. He was forced to retire from the race after 101 laps, being classified 23rd. Al Miller had qualified one of the 1962 chassis in 31st position on the very last day of qualifying but finished a creditable 9th.

For 1964 however, USAC outlawed the use of 12-inch tyres. This forced Mickey Thompson to put his cars on the smallest size of tyres available: 15 inch. Mickey wouldn't be Mickey if he didn't have something special up his sleeve. He used specially made 15-inch tyres that were 11 inches wide, contrary to the 8-inch wide tyres used by the opposition, all in order to enhance grip and traction.

The ban on the 12-inch tyres was announced in 1963. There was a lot of testing at the Speedway in November ’63. Thompson showed up for tests with the 'Rollerskates', still fitted with Chevy engines, on these new tyres. Thompson had Duane Carter and Dave MacDonald driving the cars on November 26th and 27th. Neither drove very fast since the increased wheel size had changed the roll center. (34)

Carter was reported to have hit 146mph but this being the maximum possible. Despite all that the team tried, the car wasn't cornering well. At the end of the day, Thompson left and was reported to ”think over what chassis mods will be necessary to restore proper roll center” (34)

The original 1963 'Rollerskate' was designed by John Crosthwaite. However, Crosthwaite was no longer involved in the modifications done to his cars ahead of the 1964 race. Shortly after the 1963 race he left the Mickey Thompson organization and went to work for Holman-Moody to work on an Indy project for them. Surprisingly enough, Holman-Moody (a major ally to Ford in US racing) lost the Ford backing for such a project and by December 1963 Crosthwaite had joined BRM. (40)

Information on what changes were made is confusing. There are reports that some new suspension components had been made (35) but also that the suspension set-up of the car wasn't yet altered because of the larger tyres when practice began at Indianapolis in May 1964. If the tyre change was not enough in itself, the cars had more radical changes compared with the year before.

Ford had upped the ante for 1964. In 1963 the Ford engine had been slightly reduced in capacity, and was an aluminium version of the Fairlane pushrod V8 that put out a decent 375 hp on gasoline fuel. For 1964 Ford introduced a new engine, still using a reworked version of the Fairlane cylinder block. It was now fitted with double overhead camshaft cylinder heads with 4 valves per cylinder, thus being a 32-valve Quadcam. This engine was made available together with factory support to a number of selected teams that entered rear-engined chassis. Thompson managed to secure no less then five of these engine deals for his cars.

Besides that, Thompson altered the bodywork of his car. The bodywork in front of the front wheels and between the front and rear wheel was full width, the front wheels were no longer standing free but surrounded by bodywork and actually entirely enclosed as in a sportscar. Streamlined as it looked, thus enhancing top speeds, little is known in hard facts and data about its actual effects on the handling of the car. There is much talk about the car being very unstable at speed due to lift. Now, lift was a known phenomena on race cars of the era. In fact, the story goes that even Colin Chapman, the designer of the Lotus cars, was surprised to find out that (in the mid-sixties) when measuring the ground clearance of his car, it was at its lowest point while stationary in the pits. The Sears Allstate Special, however, was said to be highly unstable. Aerodynamics were still in their infancy at that time. Streamlining was often carried out without giving any attention to maintaining roadholding. Many slippery, low-drag cars were dangerously unstable. With the knowledge of today, one can instantly see how streamlined the front part of the car was. But it is also instantly visible that the nose looks as if it generated no downforce whatsoever but generated lift instead.

It is interesting to mention that in an article appearing in print in what appears to have been a Long Beach area newspaper (33) Thompson stated that the cars had been tested at Indianapolis in November and that they wouldn't handle because of too much body roll due to the higher center of gravity, But Thompson then continued by telling that “The car is in a wind tunnel now”.

Pictures of the November 1963 tests showed that the car was still using the 1963 bodywork shape, thus it seems most logical to expect that if indeed a car went into a wind tunnel was one that started out as a 1963-shape car. But did the inspiration for the 1964 bodywork came from these tests? And more interesting, was the eventual 1964 bodyshape ever tested in a wind tunnel too? Or were there at least parts ever tried on the 1963 car that looked like what was used in 1964?

The Thompson car had an approximately 45-gallon, rubber-bladder fuel cell, located in the left sidepod of the car. The rubber bladder wasn't stored within a metal protective box, the fuel filler was connected to the bladder itself as well as onto the all enveloping bodywork. On first sight the car appears to be standing rather high on its wheels, having a fairly high ground clearance.

The car did not have asymmetric suspension in order to create a left side weight bias. Another highly unusual feature was that the right rear wheel was also steering, only the left rear wheel had no steering function. Duane Carter had tested this setup in the winter of 1963/'64 at the Riverside track and told he was terrified by the car. (3, p.524)

Three cars were entered, the titanium chassis car under #82, the red-coloured #83 was entered for rookie driver Dave MacDonald and the third car was the white #84. According to the chassis record of legendary Bob Laycock the #83 was the chassis used by Duane Carter the year before.

The majority of the other entrants and drivers looked at the Thompson cars with some hesitation and suspicion. First of all, they belonged to the much doubted, questioned and by some people hated rear-engined 'funny cars', the challengers of the establishment and their traditional beloved Offy roadsters. Their reputation had not been stellar if it came to roadholding. Nevertheless, fitted with factory Ford engines and benefiting from the full support of the Ford factory, the Thompson cars could well turn out to be serious contenders should the team succeed in extracting the potential hidden within the car.

The Ford engines were prepared to use alcohol fuel in practice and qualifying to benefit from the higher power output that methanol-based fuels enable. For the race, however, the intention was to run on gasoline fuel, as a link to the Ford production cars. The DOHC Ford V8 was derived from a production block. Using gasoline meant sacrificing some power (some 40 to 50 hp) but fuel consumption figures were much better so at least one, if not two pit stops could be avoided by using gasoline. One stop had to be sufficient and in case the tyres could cope with at least half a race distance, a Ford car could save time in the pits by needing much less fuel stops. In Danny Miller’s book Eddie Sachs, the clown prince of auto racing, however, a statement can be found credited to Mickey Thompson telling us he wasn’t in favour of using gasoline but Ford mandated it. (3, p.550)

More details about this can be found in Eric Arneson’s book on Mickey Thompson (9). Thompson mechanic Bill Marcel explained that Mickey Thompson was concerned about the safety but there was the fact as well that the engine ran hotter and that the car didn't have enough radiator area for running on gasoline. Thus the car had an overheating problem. Requests to run on alcohol were turned down by Ford and made impossible since the required parts in the Hilborn fuel injection systems necessary to run on alcohol weren't made available to anyone else but Ford. (9, p.147)

One of the mechanics working on the Thompson cars was Englishman Peter Bryant, who immigrated to the USA in April 1964 and joined the Thompson outfit. In later years Bryant got involved in Cam-Am racing and made a name for himself in that discipline. In later years he published his memoirs in a book entitled Can-Am challenger. This book became one of the few publications giving information from within the Thompson group. His skills as a mechanic and engineer make that his observations included in his book of considerable interest. I hereby reproduce a few of Bryant's observations.

Regarding the fuel tank, this is how Pete Bryant described it in his book:

“There was a single large fuel bladder, holding about 44 gallons, on the left outside of the frame in a fiberglass body shell supported, by the fill neck, which was anchored to the inside frame rails with a loop of steel tube and a small bracket. The only support for the fuel cell was the moulded fibreglass body housing and a flat thin magnesium plate beneath the tank, braced by two steel straps hanging from the top rail of the frame.” (1, p.147)

Bryant expressed his concerns about the crashworthiness of the car, given this type of fuel-tank installation. (1, p.148)

In another publication Bryant is quoted as having said the following about the fuel-tank installation of the car:

“That was one thing I didn’t like about the car from the beginning. The car really needed some outriggers, another set of frame rails outside of the frame. It Indy, if you got in trouble, you were definitely going to hit the wall, and on out car the fibreglass body was the only thing holding the gasoline bladders in place.” (9, p.142)

Regarding the rear-wheel steering, Bryant told that the rear wheel steered to the left when the driver turned to the right as long as the driver didn't made more than half a turn. Once turned in more than half the wheel went into the opposite direction. Bryant wasn't impressed with the system at all and wanted it disconnected. (1, p.148)

Bryant felt that the chassis didn't have much torsional stiffness. He described it as follows:

“The chassis were so flexible that if you held the rear end rigid, you could twist the front end with a wooden broomstick.” (1, p.151)

Bryant was assigned to the #82, the titanium-chassis car, and fabricated frame enforcements that were to be put on the car once in Indy. (1, p.152)

An evaluation of the 1964 car, compared with the 1963 version

Denny Miller’s biography on Eddie Sachs (3, p.505) as well as Eric Arneson’s biography on Mickey Thompson (9, p.136) contain some info as to what Thompson had said about his 1964 car compared with the 1963 car. According to Thompson he had originally fitted the cars with ground effect bodies that were not permitted and had to be taken off. Originally, the ground clearance was only 2 inches but he was forced to run them with 4-inch clearance. Thompson also claimed that he initially had skirts fitted on the car which were consequently banned as well and because of all the aero appendages that had to be taken off, the car lost its downforce and began to lift instead. Arneson’s book (9, p.136) also mentioned that a driver-operated rear wing had been installed but was taken off. If true, that would mean that Mickey’s car preceded Formula One cars with driver-controlled wings by some four years and also had one before Jim Hall raced his Chaparrals with such wings.

According to Thompson, he felt that the technical committee made things difficult for him since he didn’t yet belong to the Establishment. (3, p.505)

Let’s take notion of this information as being in existence but since there is little if any approval of all these statements to obtain, it appears as if it is only part of the ongoing myths about the cars. On top of that, it is difficult to argue about a car’s configuration in which it eventually never ran, if it did exist to begin with. So let’s stick with the cars of 1963 and 1964 that did make it onto the track.

Duane Carter drove one of the 1963 'Rollerskates' in the race that year. Initially he was assigned one of the 1962 cars but when that car caused trouble and the 'Skate' assigned to Graham Hill was still open, awaiting the return of Graham, Carter took over that car. He is cited to have said the following about the car:

“So we pushed it in line, took the three laps to warm it up and qualified. I think we were 15th fastest out of the field and I had only three laps in the car. It was a good automobile.” (3, p.473)

It's interesting to notice that the experienced Carter managed this with a new car he hadn't driven before. It makes one wonder what the 1963 'Skate' in the hands of experienced drivers could have achieved from the very beginning. It also must be noted that Carter seemed to have a nick of liking unusual cars. One year later, in 1964, he drove one of the two weirdest cars ever at the Speedway, the Smokey Yunick Sidecar, and kind of liked that car. He also drove the Ferguson-Novi P104 4WD car and credited this as the best car he had driven that year. Jim McElreath, on the other hand, complained that the P104 felt big and heavy and elected not to drive it.

Carter was considered for a drive in a 1964 Thompson but being a Champion spark plug contracted driver, he could not step into a 'Ford ignited by Autolite' car. We can only wonder how much help Carter could have been, using his experience the 1963 version of the car. That is, if the use of the steering right rear wheel didn’t scare him of after his experience with that setup a few months earlier.

According to literature, the suspension setup on the car wasn't yet changed over the original 1963 chassis. But the changes to the 1963 and 1964 specifications must have had dire consequences for the overall balance of the car.

First, because of running on 3 inch larger wheels, the center point of gravity (CG) was raised with 1.5 inch.

The car was tested with such wheels and in a Los Angeles Time article Mickey stated: “The car wouldn’t handle. There was too much body roll due to the high center of gravity.” (9, p.136)

Then the pushrod Chevy V8 engine was replaced with the Ford Quadcam V8. It has been stated that because of switching to the Ford the weight of the car would increase slightly, although no figures were given. (35) But it is interesting to have a closer look at this matter since some of the conclusions on the effects this engine change had on the car can be deducted. Exact figures of how much the Chevy weighed are not available but it was told to be light. On first sight, however, it seems more than likely that the replacing Ford was heavier than the Chevy, primarily because of much more hardware placed above the cylinders due to the Quadcam four-valve design. One feature of the Ford was however a certainty. Its GC had to be higher than that of the Chevy. The latter had the for a V8 classic configuration of inlets within the Vee, and exhausts on the outside. The Ford Quadcam on the other hand had the exhausts within the Vee, thus within a higher position than on the Chevy. The inlet tubes and fuel injection systems were located on top of the cylinder head, between the camcovers, thus also way above the crankshaft. All of this made the Ford larger and having more hardware (= weight) above the crankshaft, and so rather top-heavy. Even if the Ford engine was lighter than the Chevy it replaced, which looks doubtful, it still had a higher GC, which was the second reason why the GC of the entire car was higher compared with the original 1963 design. Assuming the Ford was indeed heavier than the Chevy, the GC of the entire car didn't only get higher but went backwards as well, changing the overall balance of the car even further.

Mickey Thompson and his crew had a job at hand when the track opened.

The 1964 “500” practice and qualifying

Due to the test sessions held before practice began, Mickey and Dave were both cautious about their chances of victory. In the Long Beach Independent Mickey confessed that he didn't expect to win the race but still believed he had a chance. He also confessed that he and Dave were in a learning position. He wanted to see how the car acted at Indianapolis and how Dave would find his way around. (9, p.137)

The very same article also had a quote by Dave MacDonald.

“Driving at Indy is not as much fun as some of the other types of driving I do. Everything has to be just right – there is absolutely NO room for error. I like the way Mickey’s car handle, and I think we have a good chance to do well on Memorial Day. But we’ll have to run over 150 miles per hour, and I haven’t done that yet…. Mickey’s cars handle differently than sports cars. You have to drive them through the turns. You can’t just throw them into a turn and slide through. Not if you don’t want a few tons of retaining wall on your back. Believe me.” (9, p.137)

The Thompson team started the month with the intention to have Masten Gregory qualify and race the blue #82 titanium chassis car and Dave MacDonald doing the same with the red #83 with the white #84 as a spare, to be prepared after the other cars had qualified. Dave passed his mandatory rookie test on May 2. He was the first of the rookies to pass the test. The start of the entire program was pretty promising.

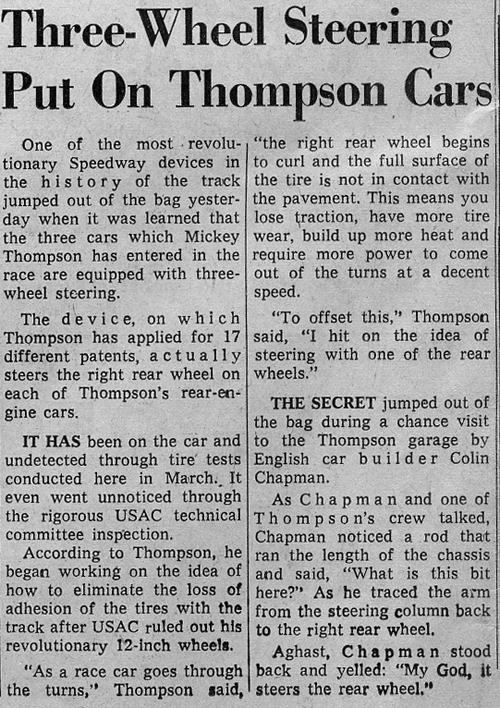

The secret of the steering right rear wheel leaked out very early in the month. This is how the Indianapolis Star newspaper announced it in their May 4 edition.

Pete Bryant described in his book Can Am Challenger that Gregory noticed his car “darting” under braking at the entrance in Turn One. According to Bryant it was really bad and it was also noticeable how the nose lifted. Bryant and Thompson who had a look in Turn One also noticed that it appeared as if the car raised its outer front wheel. Bryant diagnosed 'bump steer' that needed correction and suggested a bunch of other modifications as well. Since there was not enough time before qualifying the team (or more correctly Bryant) focused on curing the bump steer while Thompson worked on the aerodynamic problem. Bryant discovered an amount of bump steer that made him wonder how the drivers could keep their cars in a straight line. (1, p.159)

It is interesting to point out that In Arneson’s biography on Thompson, Bryant is quoted in a far more negative manner on the car:

“The car was the most ill-handling piece of shit I ever worked on. The chassis stiffness was terrible, and the suspension geometry was all wrong.” (9, p.140)

Another mechanic with Thompson, Bill Marcel, had said:

“The cars, as designed and built after going through tech, did not have a stiff enough chassis. We kept jacking weight around, changing the shocks… it was never ending. They’d take the car out on the track, run three laps, bring it in, and change everything again. We were all bitching and moaning.” (9, p.140)

The 1964 Clymer quoted Gregory as having said:

“The front end lifted on the straightaways and made the steering so light I didn’t have control.” (5, p.108)

On May 6th Thompson had the red #83 fitted with wool tuffs at the front and sent out MacDonald to drive at the track while a photographer took pictures of the car with a long-range lense in order to evaluate the airflow over the car, using the directions of the wool tuffs. Both Gregory and MacDonald liked the cars a bit better although they still complained about oversteer. That same day however, Gregory had a crash which made him so upset that he left the team and spoke about the Thompson car to Jack Brabham as being the most lethal, evil-handling car he ever drove. Curiously enough, it would take until May 20 before the local newspapers printed the news that Gregory and Thompson had parted.

Peter Bryant then got the job to alter the suspension setup on the cars as he had suggested and worked for days and nights to modify them. As a result of the long-lense pictures, the inlet of the radiator was lowered to counteract the lift. The tops of the wheel arches were taken off in order to avoid air building up in them. MacDonald was sent out on the track with his modified car on Friday May 15 and clocked a 155 average in a car that had a little understeer.

The big question remains: if Thompson had figured out in the November ’63 test sessions that the suspension geometry had been all wrong for the 15-inch tyres, and also told the press that he wanted to think over the solution of this problem, what had he done to the cars since November ’63 to improve their situation? Evidence suggests: not much, if Bryant still had to do all that workat the track in May.

Dave MacDonald seen in a practice session

One day later, on Pole Day, MacDonald qualified his car with an average of 151.464mph in 14th position, the middle of Row 5. He was second fastest of the rookies, Walt Hansgen in 10th was the fastest. The loss of speed compared with the previous day was credited by Peter Bryant to the fact that Mickey Thompson had played with the spring setup. (1, p.163)

Bryant also told that Mickey Thompson was “over the moon” after having qualified because Masten Gregory had told to Jack Brabham “our car was the most ill-handling car… and it was until we fixed it… then we qualified ahead of Brabham.” (9, p.141)

This comment, however, must be put in some perspective. Dave MacDonald did indeed qualify in front of Jack Brabham, but this was partly a result of the qualifying procedures at Indy in which drivers are ranked in the sequence of day they qualified, regardless of their speed. Brabham qualified a week later than MacDonald and was thus put behind Dave (25th), despite the fact that Brabham had a faster qualifying speed. And in defence of Sir Jack, he missed out on qualifying on the second day by a matter of seconds. He was ready to go as the final qualifier on Sunday May 17 but Troy Ruttman hadn't cleared the track at 6:00 exactly when the gun went off. According to the rules Brabham was not permitted to start his run after 6:00. This forced the Australian into the unhappy situation that he had to practice and qualify for the Dutch Grand Prix the next weekend on Friday, then fly to Indy to qualify on Saturday and rush back to Zandvoort to race on Sunday!

So in his own book as well as that of Arnesen, Bryant suggests as if over time during practice, the cars became better. Besides that, mechanic Bill Marcel confirmed that the car was improved during practice. Marcel is quoted as saying:

“Somebody came to the conclusion that the chassis was flexing, and the decision was made to make it more rigid by taking the aluminium panels that were in there in the birdcage frame and drill holes and pop-rivet the panels. Another mechanic and I stayed up all night the night before qualifying, pop-riveting all the panels to make the car more stiff. We were so tired that we slept in the next morning and missed the team picture when the car qualified.” (9, p.140)

There is however one printed comment which says the opposite was the case (7, p.68). In addition, there was another comment made by an unnamed Thompson crew member. This mechanic said the cars should have been withdrawn after the first days of practice and handling had become even worse after the mandatory use of 15-inch tyres. He also stated that the team went trough drivers in a manner described as “As soon as one driver would get in the car, another would get out.” The crewman also stated that Thompson knew of the problems but that his ego got in the way. (7, p.68)

A bit off-topic but worth mentioning: if the chassis was said to be flexing in 1964, it makes you wonder how bad it must have been in 1963 and how Duane Carter managed to get on terms with the car in the first place.

We got something of an answer on this question in January 2016 when we were contacted by the son of John Crosthwaite, the designer of the original 'Rollerskate'. John Crosthwaite Jr informed us that his father had a non-published autobiography in which some comments were made about Indy 1964. Crosthwaite Sr had been at Indy for qualifying, together with Tony Rudd, since BRM was thinking about an assault at Indy in 1965. Among the comments in Crosthwaite's biography are a few observations about the changes to the cars. According to Crosthwaite Jr, this is what his father had written:

"In May 1964, I went with Tony Rudd to Indy for qualifying only, just so he could look around and I was truly horrified to see what Mickey had done to my rollerskate (now with 15inch wheels). To get the huge overhead cam. Ford racing engine into the car, they had just bent the 1inch dia. engine compartment tubes, round the engine - this meant the chassis had no rigidity at all and would just flex and eventually break. I told Fritz (Voight) this wasn't on and he just shrugged. I can't see how it got through technical inspection! I wish I had made more of a fuss about it, it might have saved drivers lives." (40)

Crosthwaite's son also stated that although at the time (1964) his father and Mickey Thompson were not on speaking terms Crosthwaite Sr nonetheless respected and admired Mickey. Crosthwaite and Thompson spoke again shortly before Thompson's death and Crosthwaite didn't have negative feelings towardsThompson because of the eventual events of 1964 discussed later on. (40)

Based on John Crosthwaite's observations in 1964, it appears as if the original cars of 1963 had been more rigid, thus possibly explaining why Duane Carter never mentioned such chassis flex that year.

Meanwhile, Eddie Sachs, driving a Shrike-Ford had endured a difficult practice period with malfunctioning Ford engines but eventually was ready to qualify on Pole Day as well. Regrettably for him, he had an accident and the car needed repairs. Eventually Eddie became the fastest of the second-day qualifiers in 17th spot, right behind Dave. (3), (5)

A practice shot of Eddie Sachs in his American Red Ball Special, a Shrike-Ford, innovative thanks to its magnesium alloy monocoque.

Dave had done some practice again that day but blew an engine in the process. (5, p.119) Sachs’ teammate was Jim Hurtubise, driving an Offy Roadster built by himself, using parts of the 1963 Watson driven the year before by Eddie Sachs. In Jim’s biography, written by Bob Gates, the following passage can be found on page 184. After mentioning how Jim qualified on Pole Day, Gates continues as follows:

“Just two days before, both MacDonald and Thompson spoke candidly of the difficulties they were experiencing. “The car doesn’t feel right yet,” stated MacDonald. “The front end wants to lift, and I just can’t seem to handle it coming out of the turns.”

(…) Thompson explained why. “The car was designed for the small, twelve inch diameter tires, but they were banned. And, that’s got my suspension system messed up. The roll centers aren’t in the right place, the mounting points aren’t right. Anything I do to help it will be a compromise, and I’ll never get it right.

But we’re making some aerodynamic changes in the car,” Thompson continued, explaining what he was doing to correct the problem. “I’m trying to control my car with a certain amount of lift. It’s still lifting too much, but I’m trying gradually to decrease it.” (6, p.184)

Gates used some of the comments above as well in his 2012 publication about Troy Ruttman (37). In private correspondence I had with Mr Gates he informed me that the original sources in which he found this information had been the local newspapers in Indianapolis.

Veteran driver Eddie Johnson was hired to drive a Thompson on May 19 but he had a crash in the repaired #82 titanium car. That car certainly had a workout in having spins and accidents since, apart from the Gregory mishap, Dave MacDonald had driven it once in the week before and spun off as well. Dave told that he had spun since the car wasn’t his own car and the blue one felt differently.

It was also reported in the newspapers that Chuck Arnold was hired to drive the white #84 but this car eventually went to Eddie Johnson, who qualified it during the second weekend of qualifying with an average of 151.9mph for the 24th spot. For a number of people it was because of Eddie’s experience with the track itself and 'only' having to adjust to a new-for-him rear-engined car that he was faster than Dave. Perhaps another satisfaction for Thompson and his team was that Eddie qualified 24th, a touch faster than Jack Brabham who was 25th. On speed, one of the Thompsons was indeed faster than Brabham.

Arnold was seen in the #82 and he too spun that car on May 24. Just about every driver who took out the #82 spun in it. As to why, I never found an explanation but my own personal theory about it is as follows.

The titanium chassis was said to be lighter than the chassis of the sister cars. This should mean that the complete car was lighter as well. However, due to the lighter chassis frame it meant that the GC of the car had moved a little to the rear, meaning that the front of the car was a lighter than that of its sister cars. So even less weight at the front to counteract the lift generated by the front part of the bodywork.

However, there is no way of confirming this theory, so it remains speculation.

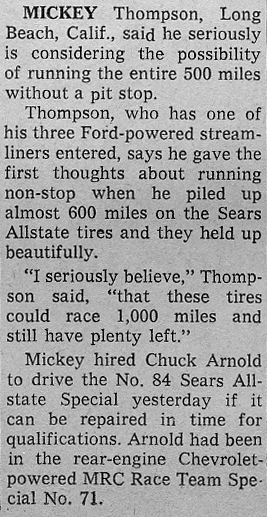

Earlier that week, there was something to be found in the local newspapers that, with hindsight, may have had dramatic consequences. An article printed on Wednesday May 20 in one of the local newspapers stated that Mickey Thompson was considering trying to do the race without a pit stop for new tyres since their behaviour indicated they were more than capable of going the full distance.

This news raises thoughts. With all the troubles to sort out the cars decently and make them work, did the team still have obtained sufficient data to make this assessment with any comfort and faith? And had they done some tests with the car fully loaded with fuel already in order to sort out the tire wear after doing a simulated long distance run in order to validate the tire wear when the car was heavy? Because running without a pit stop meant that the car would need a tremendous fuel tank capacity in order to finish the race without a fuel stop.

Could this May 20 Indianapolis Star article be among the sources causing so many people to believe the Thompson cars were fitted with massive fuel tanks in order to do the entire race without a pit stop?

During that weekend, just at about the very last moment possible, Masten Gregory came back to the team and in the final quarter of the time trials he made a qualifying attempt in the blue #82, but with 146.038mph he was too slow. It only made him 2nd alternate. (1, p.164)

During the practice period, Dave MacDonald had caused some concerns with several people at the track, among them several of his peers and Mickey Thompson. Dave preferred a driving style with a bit of oversteer in the car so he could hang out the tail in the corners, a driving style he was familiar with in sportscar racing. Thompson on the other hand wanted Dave to take the corners as smoothly as possible. Oversteer was considered a danger at the speedway. It is said that Dave was warned about his driving style by a number of people. It must have worried quite a few, considering the fact that the Thompson cars had earned themselves no good reputation because of their crashes and spins, that one such car was in the hands of a driver who was inexperienced in Indy and was using a driving style unusual to ovals. Dave MacDonald himself also had some concerns about this situation as the quote from Gates' Hurtubise book proves.

Another telltale story can be found in Bill Libby’s biography on Parnelli Jones, Parnelli. On page 194 you can find the following paragraphs with quotes credited to Mickey Thompson and Dave MacDonald.

“Thompson, bristling from the ridicule his unusual creations had drawn, said, “We’ll show everyone.” One of his drivers, MacDonald, ( … ) was not so sure. (…) He was a pleasant youngster, who seemed to lack confidence.

“I never driven anything like this,” he said, “When Mickey offered me a ride in one of his cars in the 500, I said 'of course'. Who wouldn’t? But here I feel like I’m learning all over again. In sportscar racing, if you get in trouble, there are escape routes, but here there are only the walls. It’s my first time here and if I get in troubles, I won’t know what to do. My car is handling a little funny. I just can’t seem to handle it coming in and out of turns. But Mickey says I’m just here for the ride, to learn this year, so I can take it easy. I hope it goes allright.” (11, p.194)

The question remains why Dave continued driving the car. That had lots to do with the fact that Dave feared that, should he leave the team, it would end his future with Ford. Being taken on with the Ford program, after all the driving he had done for Ford in the Cobra program and NASCAR, he believed he stood a chance of being taken up by Ford as a works-supported driver. And if there was one American car company preparing to enter the racing scene big-time, world-wide, it was Ford. For an American driver, being able to hook up with Ford in one of these programs meant a big promise for his career and future. Dave wasn't willing to risk losing his big chance, and so stuck with the car and tried to make the best of it.

One of the persons he told about the lift habits of the car was his father.

It's certain that Mickey Thompson must have released a breath of relief when Eddie Johnson qualified the second car. Remember, he had a deal for five of the Ford engines and got only two cars in the field. No doubt that some high Ford officials must have had their doubts whether placing that many engines with Mickey had been such a good idea. Jim Clark and Dan Gurney at Lotus and Rodger Ward at Leader Cards were the three top Ford drivers. Eddie Sachs was another potential contender, as was Bobby Marshman in a Lotus, fielded by Lindsey Hopkins. But the two hottest drivers, Parnelli Jones and A.J. Foyt, each had a rear-engined car but hadn't been given Ford engines. Many insiders rated this as a wasted opportunity by Ford to further improve their chances.

It must be noted that both men didn't like their Offy-powered rear-engined cars and it remains a question whether they would have liked it had they been Ford-powered. Especially in the case of Foyt it is interesting to mention that he rejected his car, a Huffaker-built chassis. It was one of the MG Liquid Suspension specials. Once rejected by Foyt, the car was taken over by Bob Veith who qualified it on the third day in 22nd spot and was classified 19th after retiring with engine trouble on lap 88, having run as high as third. (7, p.66)

Thompson’s team had truly been the weakest link of the Ford army. How much stress it may have caused on Mickey and his people is anybody’s guess.

With qualifying over and done with, there was only Carb Day to check out the cars before the race. Before that, the Ford engines in the Thompson cars had been sent to Dearborn to be entirely rebuilt and converted from the use of methanol to gasoline.

Once on Carb Day, MacDonald was reported to have driven some 5mph faster than he had done in qualifying. There are reports that Dave did drive his car with a full fuel load that day (24), other stories with comments from other people deny that. Mechanic Bill Marcel told that on Carb Day the team was still working on setup and maybe carried 26 gallon at the max. (9, p.141) But a speed improvement of 5mph on his qualifying suggests that, whatever fuel load he carried at that time, the handling of the car was improved quite a bit and/or Dave must have got an increased amount of confidence in his car to take it out so fast. Bill Marcel told that Dave was happy with his car. (9, p.141)

According to Thompson, MacDonald’s car got a new nose which improved the handling and Thompson claimed that he had sorted out the car. (3, p.551)

Whatever the case, Carb Day was about the only chance that Dave ever had to get a feel for his car with a full fuel load and in traffic. Practice, let alone qualifying rarely offers the opportunity to drive at a track with so many cars as during the first laps of the race. So had he used the opportunity?

Denny Miller tells about how famed mechanic Bill Stroppe noticed that prior to the race, the car appeared to be fully loaded with fuel, with Dave indicating to him that he hadn't driven the car with a full fuel load yet. (3, p.531)

A number of drivers were still weary of Dave MacDonald but more of them were concerned about the car he drove. There is no confirmation of this but it is published that on Carb Day pole sitter Jim Clark followed MacDonald for some laps, went to see Dave once the driving was over and advised him to get out of the car and withdraw from the race. (7, p.64)

Once Carb Day was over, all that was left was Race Day to conclude the Month of May in 1964. It had been quite a month with battles between the new kind of car (rear-engined) against the well and proven roadsters, and the tyre war between Firestone and Goodyear. The race had the promise of becoming one of the most memorable in the history of Indianapolis.

Which indeed happened, but for all the wrong reasons.